Since 1998

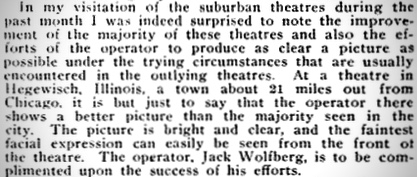

Pretty much this whole Pizza Hound thing has been about mystery and the joy of discovery. It has been about seeking out delicious pizza, but also about learning about the people and places in all corners of Chicago. While on the one hand outwardly focused, the process has often been, on the other hand, honestly, conducted in a bubble. The routine of anonymous trips in and out neighborhoods and towns (some familiar and some not) arriving to look around, pick up an order, chat a bit (if at all), then leave to enjoy the pizza at home, can be pretty effective to a degree. All the while we endeavor to be friendly, pay attention, and observe, leaving the drive home and next day to wonder about where just quickly slipped in and out. But as one might guess, this process does not always work entirely well. Sometimes we leave with more mystery than discovery. For so long, we’ve tried to understand one of our favorite destinations, Hegewisch, merely through these glimpses. Instead, the neighborhood always left us slightly perplexed, leading us to rely on the same cliches of isolation and insularity that writers have applied to the community for years. Then one day we had a strong suspicion we had no idea what we were talking about.

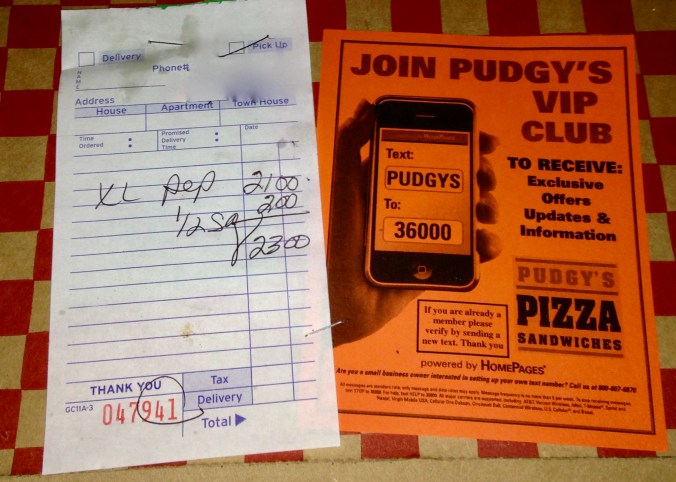

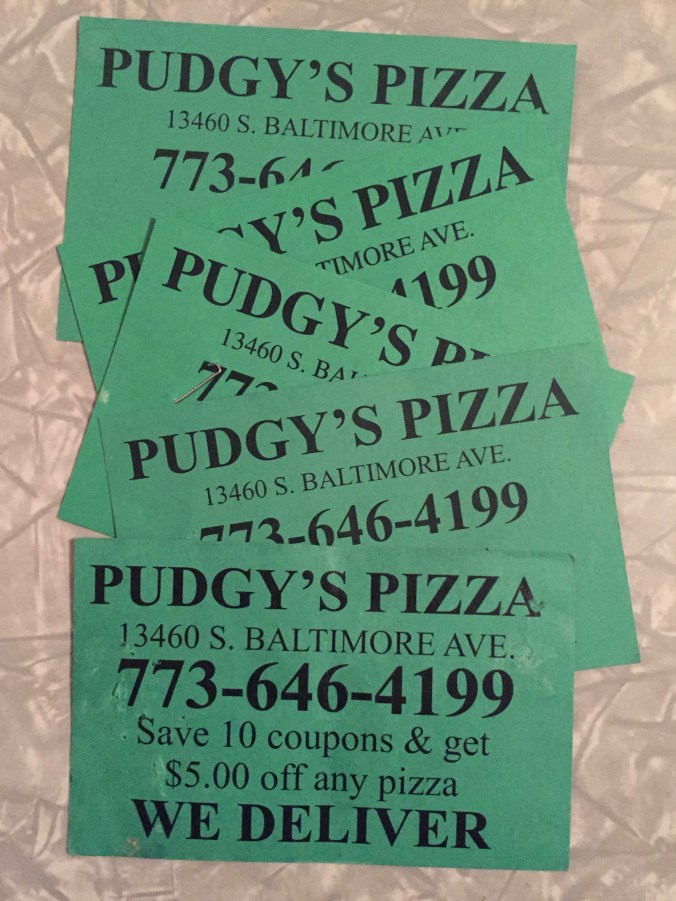

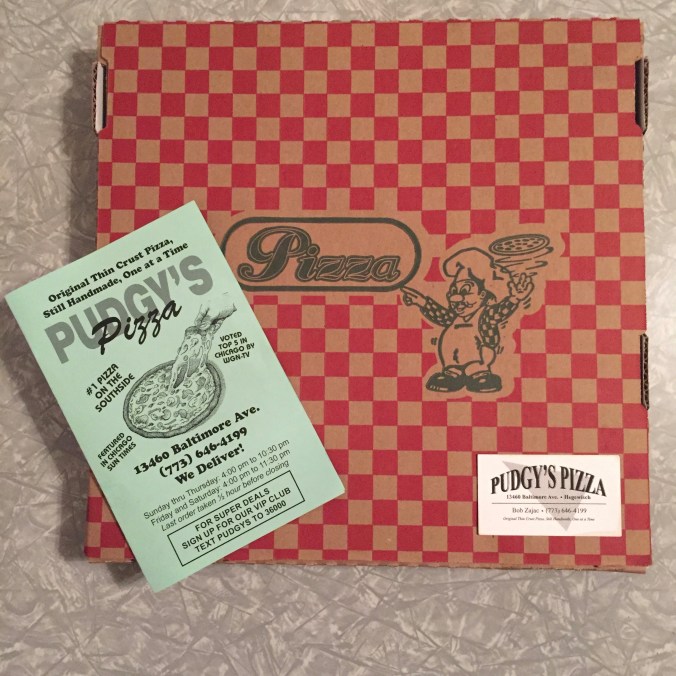

We had to do something about that feeling because Pudgy’s is the pizza that started this whole thing, and its place in Hegewisch made it an ultimate destination. Like most of the communities Ernie and I have visited, we’re not from Hegewisch and we’ve never lived there. We’ve studied it and thought about it a lot. We’ve read a few books and articles about it, too. But in the few of those that are out there, most of the time Hegewisch is presented on the periphery of the story, not at the center, which left us feeling like we didn’t really know what the neighborhood was all about.

There may be reasons for that. Honestly, despite your best intentions, Hegewisch, has a way of reminding you that you are an outsider. Insularity and isolation are not completely off-base. Maybe that isolation from the rest of Chicago does help define it. Maybe residents are guarded from dealing with all those academics who traveled there in the 1970s and 1980s to examine the devastating effects of steel industry’s shocking decline–and the lack of positive results that came from all of those studies. It could be that Hegewisch is really just a small town like any other that isn’t used to visitors without an agenda; a community that only appears in literature and Google searches because of its presence within the Chicago city limits. Or just as likely it’s from an ingrained culture of hard work and modest successes, where there’s not too much that impresses you, especially not a North Sider showing up for pizza. “Don’t you have that up there? O-kaay…” We get that.

So, from time to time, we kind of thought we weren’t. . .welcome.

Or maybe we were wrong.

Even when we felt like outsiders, we always saw signs that Hegewisch is the kind of place that if you tried, stayed, and actually proved that you gave a damn, a special world would be revealed to you. Just talk to someone who grew up in the community and truly loves it, and you’ll realize it can be a friendly welcoming place where the people are justifiably proud of their history. We were lucky enough to do just that.

But it took us awhile to get to that point.

It’s hard to know where to begin with Hegewisch. If you aren’t from there, then there’s a good chance you’ve never heard of it (which seems to be a theme expressed in almost everything written about the neighborhood over the last 130-plus years–when something is written at all). If you didn’t grow up there, there’s a good chance you mispronounce its name, too (“wish,” not “wich”). But it is also hard to know how to understand Hegewisch. The weight of the Second City, perhaps, makes doing so seem more important than trying to get at the heart of any one of the thousands of America’s small towns. And when the questions start, they really never stop: Where? Why is it there, so far from the world-famous skyline and the neighborhoods that so many people know as the city? It’s not downtown, it’s. . .uptown? Wait. . .we’re still in Chicago?

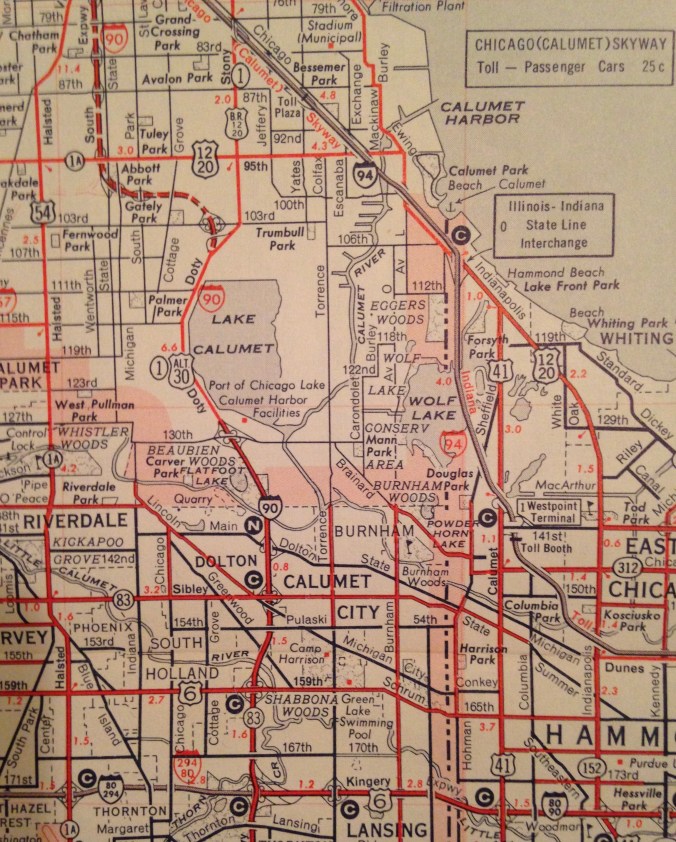

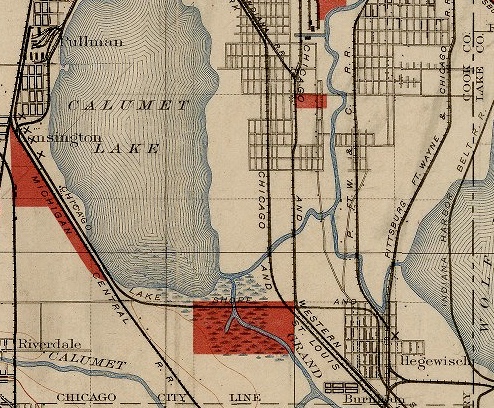

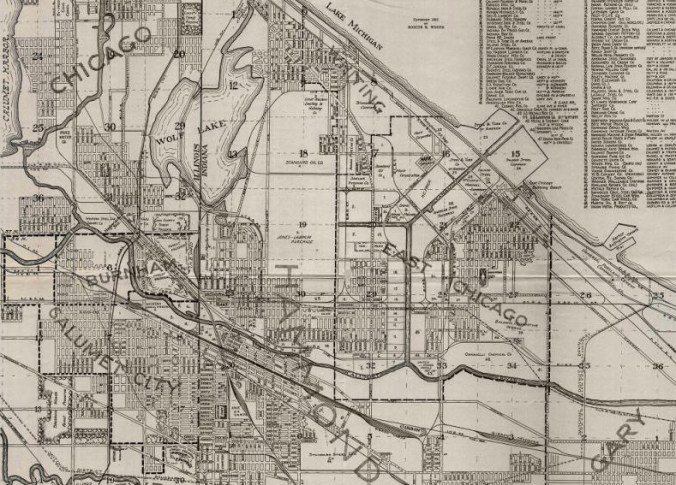

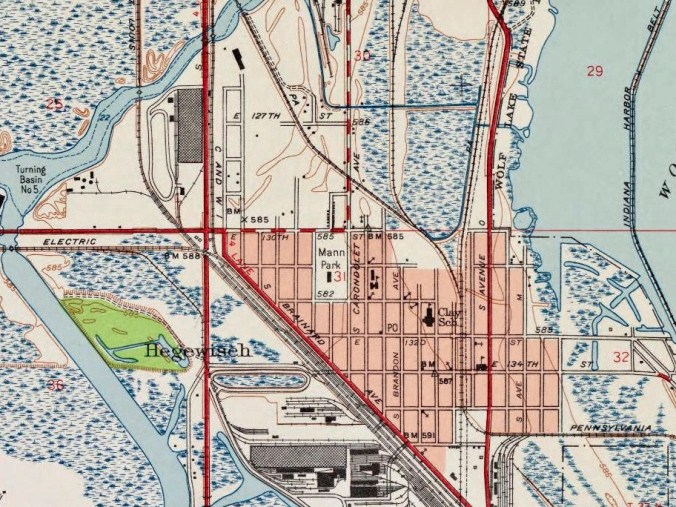

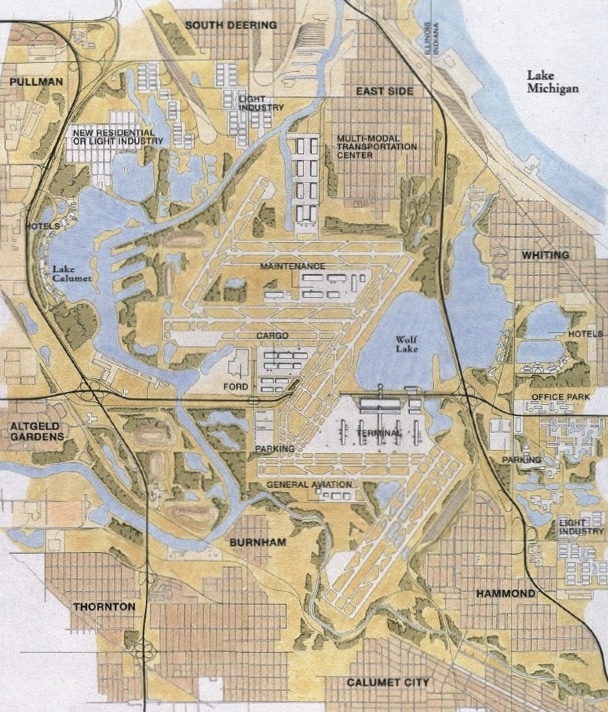

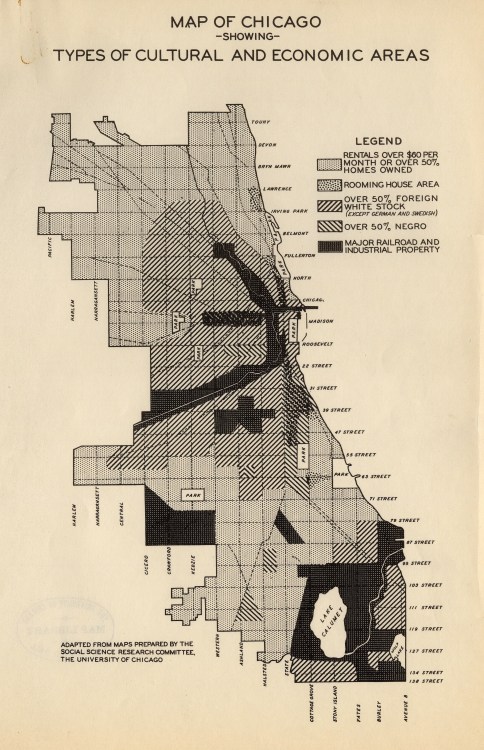

Do you see it? Near the center of the map? Between the two big lakes, just north of Burnham and Cal City?

Source: Bulk Petroleum Co. Chicago and Vicinity travel map. Rand McNally & Co. c.1950s.

Surrounded by lakes, rivers, marshes, active and dead industrial sites, railroad tracks, highways, other Chicago neighborhoods, independent Illinois cities, and even the Indiana border, Hegewisch is about 16.5 miles from the tourist hordes that pack the Loop and the Magnificent Mile on a daily basis. It is–with South Chicago, South Deering, and East Side–one of the four relatively-distant major communities that make up the traditional Southeast Side, a place where the emergence of great industrial factories brought numerous different ethnic and religious groups that have mixed for decades and decades, building their own institutions and communities within the communities. But even in that section of the city, Hegewisch has always been something of an outlier. The furthest south and the most secluded of all the neighborhoods, Hegewisch was for a long time perhaps the least diverse neighborhood in that section of the city, resisting demographic change longer than many parts of the region, too. Despite this, in the last decade and a half Hegewisch has evolved, though at a pace relatively slow compared to the shifts seen in other urban neighborhoods in Chicago. Very few places in the urban form of the Midwestern metropolis–a place were neighborhoods are in a constant state of flux, where major changes commonly occur from decade to decade, year to year–have exhibited such a tension between change and stasis, making it difficult to know whether the theme Hegewisch’s existence is one of consistency or exactly the opposite.

So, is it an independent small town, or an urban community within Chicago, south of the Skyway?

“Hegewisch (Chicago Neighborhood Under the Skyway).” Courtesy Michael McGinley.

The first time Ernie and I headed to Hegewisch and to Pudgy’s was a few years ago. Previous trips to Southeast Chicago had been made to enjoy unique crunchy fried tacos at the now-shuttered Mexican Inn on the East Side and doughnuts at the Calumet Bakery in South Deering. Quick trips had been made to farther south to Hegewisch before, too. We found a quiet small community that gave us more questions than answers, but you could say we were smitten, due in no little part to the fact that Hegewisch had a lot of local pizzeria options at that time. There was Pucci’s, Doreen’s, Mancini’s, and a place called Pudgy’s. Pucci’s was the first pizza place we had seen in the neighborhood, so that was our original choice for our first pizza in Hegewisch. We kept thinking about one of the other places, though. Pudgy’s. . .something about that one. What a perfect name. How on Earth could the pizza not be fantastic?

So, by time the Pizza Hound and I had made our first trip to Hegewisch specifically for pizza in our 1999 white Ford Escort, we had adjusted course toward Pudgy’s. We had a good feeling about it. And while we had managed to locate Hegewisch and Pudgy’s on a map, we still had to do some careful planning to get there. If we hadn’t, we may have never made it. Difficulty and even mishaps have long been part of the traveling-to-remote-Hegewisch narrative.

Source: Collier’s, November 8, 1913.

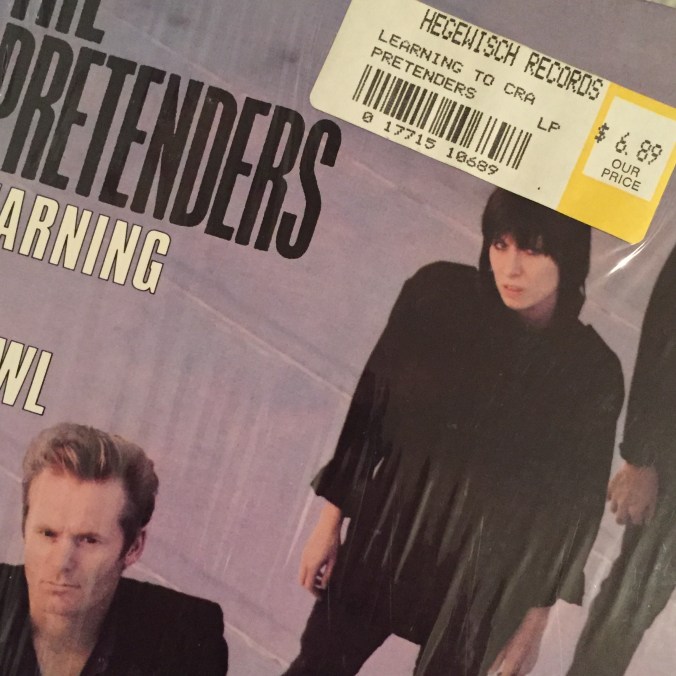

We just needed to get away, so we took a long casual Saturday afternoon drive that turned into night by the time we completed our journey. We didn’t have much money, either, so we had to dig through the record collection to fund the trip. (Goodbye, original copy of Voices of East Harlem.) Now, we could have just flown down the absolutely manic Dan Ryan, then taken the exit at 130th Street and headed east to Torrence and Brainard avenues, but of course we like to make our pizza trips in dramatic fashion. So, we drove through the hustle and bustle of downtown, then hopped on the relatively docile Lake Shore Drive. After Hyde Park and Jackson Park, we drove through the mid-rise apartments and former motels of the South Shore neighborhood, and once we hit 79th Street–the beginning of South Chicago and the traditional Southeast Side–we continued on South Shore Drive through South Chicago past numerous two- and three-flat houses, some storefronts, and a church or two, including St. Michael the Archangel, a former Polish parish that provided a then-unrecognized clue to the history and culture of our ultimate destination. We can’t remember if the new extension of Lake Shore Drive was open at the time–the part that hurtles you through the old U.S. Steel South Works site in South Chicago along the lakefront–but nevertheless we continued the way we had in past trips. And with a few turns, we crossed a bridge over the Calumet River and ended up on on Ewing Avenue, a main drag on the East Side.

The great Skyway Doghouse is on Ewing, and Phil’s Kastle, a diner that’s home to delicious hamburgers, is just around the corner on 95th Street. From there, the famed Calumet Fisheries is about a quarter-mile to the west. We kept heading south on Ewing, though, traveling beneath the massive Chicago Skyway, the namesake for the hot dog stand we had just seen, passing the main location of Pucci’s as well as a number of East Side storefronts. While expressing nuanced differences, it still essentially felt like we were in a neighborhood of Chicago, though far removed from where we had been just about fifteen minutes earlier. Pedestrians were still fairly common, and there were a lot of cars, too. Traffic can really back up on the main thoroughfares during certain times of the day. The Indiana border was very close, fittingly, just to the east down Indianapolis Avenue. We stayed in Illinois, though, and at 106th Street we made a right and headed west until we hit Avenue O, where we headed south to begin the last leg of our trip.

A former tavern at 106th and Avenue O? Look at those rounded windows! Turn left at the corner store. . .

Are you still with us?

We ask, because to get to Hegewisch, you probably really have to know where you are going. Either that or you are just incredibly lost. You probably won’t find a sign directing you there, and locating it on a map might prove unfruitful.

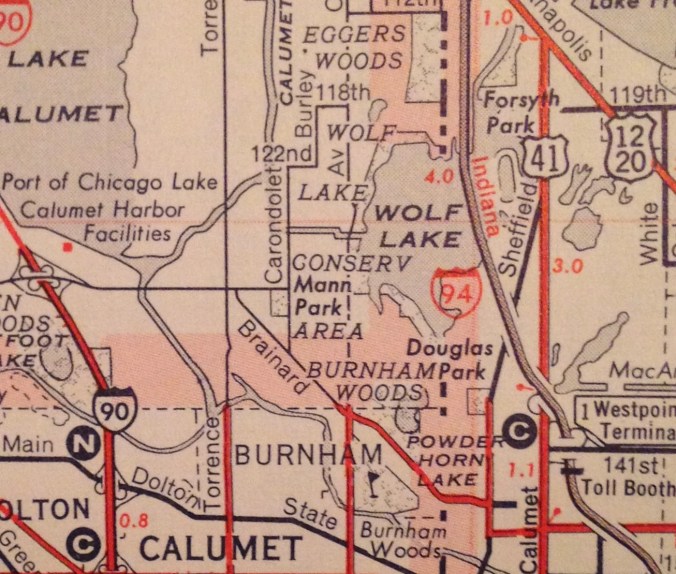

A closer look at our map. . .Hegewisch is not listed. See that triangle in middle? Right around there.

Source: Bulk Petroleum Co. Chicago and Vicinity travel map. Rand McNally & Co. c.1950s.

There just aren’t very many roads that lead directly there, either. The Southeast Side is full of hidden passages, though. If you look closely enough, you can find the one that serves as the pathway to your destination. Avenue O is somewhat like that. It passes many tidy bungalows, some of the cutest in Chicago, in fact.

Rows and rows of them.

We then passed George Washington High School and a sign for the First Savings Bank of Hegewisch, though we weren’t yet to our destination. We also saw a newer suburban-style development with a large new grocery market, a couple of fast food restaurants, and a handful of other stores. Interestingly, a rusted, decaying industrial building can be found just across the street to the south, contrasting with the strip mall, big box development that is often rather busy. Two versions of America, facing one another.

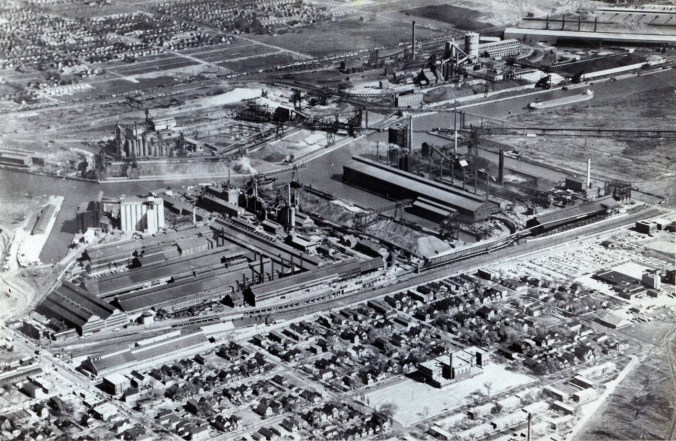

But the biggest shock is on the western side of Avenue O. There’s a stark emptiness to behold. Not so much empty, per se, but noticeably lacking something. . .something that was once there.

Rather than more rows of single-family homes or a peaceful nature scene to admire, one cannot help but note what was once there for so long. The gigantic lot is somewhat overgrown, marshy-looking with a number of interspersed trees. Some of buildings in the distance once housed several large industries. Currently, the site may be home to some active business establishments during the day–just a fraction of what was once there–but in the dark of night it can look a little frightening. In the distance stands a few lonely buildings. So lonely that my friend once quipped that there could be some guy sitting in a chair, tied up, with a light bulb just above, all the while being interrogated by a mob boss or secret government agent.

Just before 116th Street, a faded, dirty sign reads “LTV Steel.”

At this point, we were not yet to the main part of Hegewisch, but no doubt many residents of Hegewisch traveled to this site for work. Or at least some of their ancestors did after they left their homes in Europe, Mexico, or the American South just a couple of generations ago. Despite the grueling work that was once done at this site–and despite its relative emptiness now–for about a century it was considered by many to be a jumping off point to a better, brighter future. We would even meet someone special who would say he thought those days would never end. They did, though, and today, the lot is a fading reminder of what once was. . .a scar that has not fully healed.

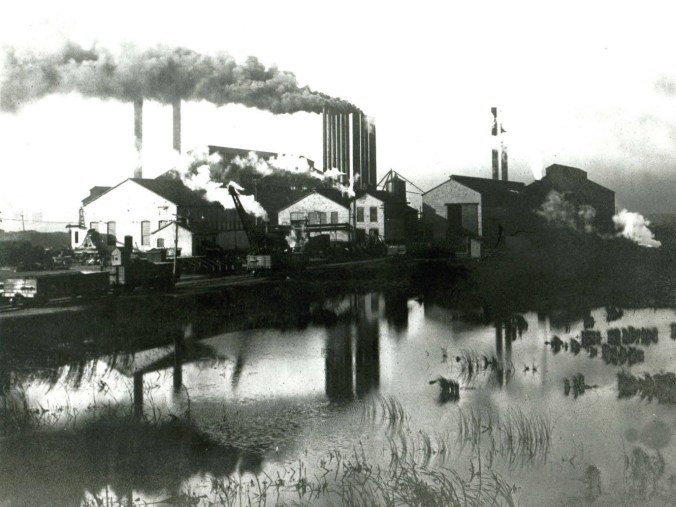

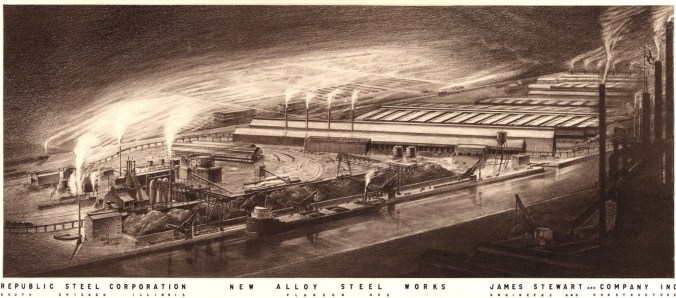

Republic Steel in an early incarnation as the Grand Crossing Tack Co., 1902. Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

It is also the site of one of the most infamous days in labor history. LTV for much of its existence was known as Republic Steel.

Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

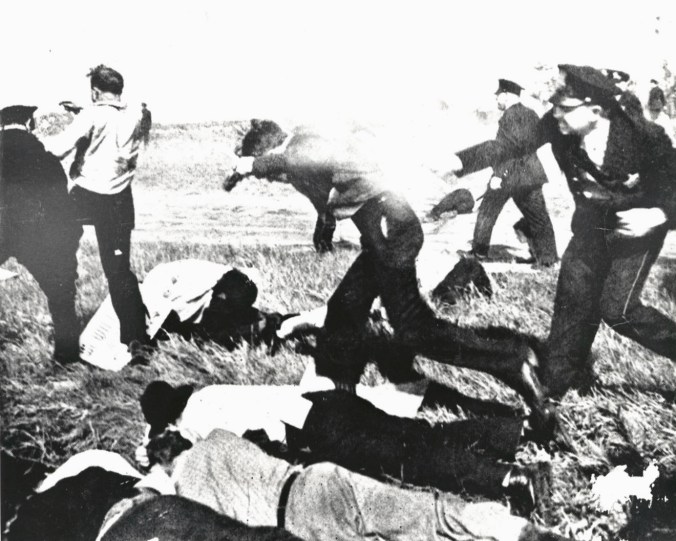

In 1937, after the Congress of Industrial Organization’s (CIO) Steel Workers Organizing Committee spearheaded the Little Steel strike, police confronted sympathetic marchers on the Republic Steel property. Tensions ran high and violence ensued.

Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

Ten marchers lost their lives and many more were injured. The event, dubbed the Memorial Day Massacre, garnered nationwide news coverage as well as the attention of Congress. Previously suppressed film footage confirmed the marchers’ account of the bloody events.

Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

A steel sculpture commissioned by Republic Steel, once located on the mill site near Burley Avenue, sits at the corner of Avenue O and 117th Street. Though it has ten metal bars–ostensibly to honor the ten victims–the company claimed they actually represented the four cardinal directions and the six steel districts. Just a half block south, a plaque honors the strikers–“martyrs – heroes – unionists”– that were killed that day by name, leaving no doubt to its intentions.

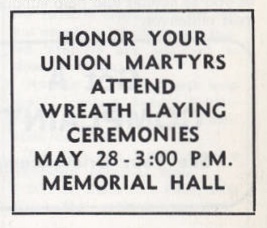

The massacre was not forgotten locally–it was even fictionalized to critical acclaim in Meyer Levin‘s novel, Citizens–and its memory played a large role in labor/management relations in the following decades. Ceremonies were held each year to commemorate the bloody event.

Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

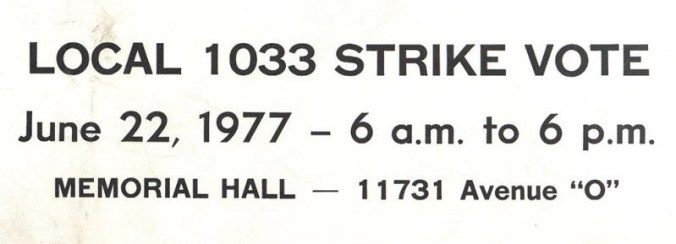

The Steel Workers Organizing Committee was a precursor to the United Steelworkers of America (USW). Local 1033, just one of several union locals representing workers in the region, served the Republic Steel rank and file until the mill’s closure.

The leadership of Local 1033 published newsletters to the members updated on current issues facing the union.

Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

Never forgetting the massacre, union members were often prepared to strike if workplace demands were not met.

Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

In the 1960s, the view from Republic Steel entrance sign looked much different than today.

Source: Republic Reports, November 1967. Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

With the steel industry thriving, a new union hall was dedicated.

Through many economic ups and downs, overtime and occasional layoffs, steel mills like Republic could be depended upon for employment and stability for generations.

Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

But by the early 2000s, all the mills in Southeast Chicago were gone. The building still stands, but with no steel to produce, there’s no need for steelworkers to meet. A church now occupies the building. The solemn marker remains, easily missed as drivers fly down Avenue O. Nevertheless, the history of local steel production is essential to understanding the economy and culture of Southeast Chicago, including Hegewisch. As a testament to this, retired steelworkers still meet in the church hall once a month.

If we didn’t keep going, we may have mistakenly concluded that we had reached the end of Chicago, because here the city doesn’t blend into a suburb as it does in many of its other corners; it just kind of fades away. Or does it? Did we pick the wrong hidden passage? We must have made a wrong turn at some point, right? Was the mythical Hegewisch really down the road at all? We kept going, knowing it was worth it. At one point, we saw an automotive parts manufacturing plant on the right with a number cars surrounding it showing that industry is still alive on the Southeast Side. But on the left, we saw an indication of the area’s even longer history: the William W. Powers State Recreation Area which, along with other nature preserves point to area’s distant past–and present–as a natural wonderland. The prehistoric Lake Chicago covered the area about 13,000 years ago, as the glaciers of the ice age receded. The area was still completely covered by the waters of Lake Michigan just 1,100 years ago. As recently as a century ago, much of the land where this lonely section of Avenue O is located was covered by Hyde Lake, a body of water just to the west of Wolf Lake (and a cause for some fun exploring). When streetcar service lines connected Hegewisch to South Chicago and the East Side, the tracks had to be built over the water.

“Hegewisch extension, on Brainard Avenue, looking south from about 125th Street and showing construction through the marsh.” Source: Electric Railway Journal, January 4, 1919.

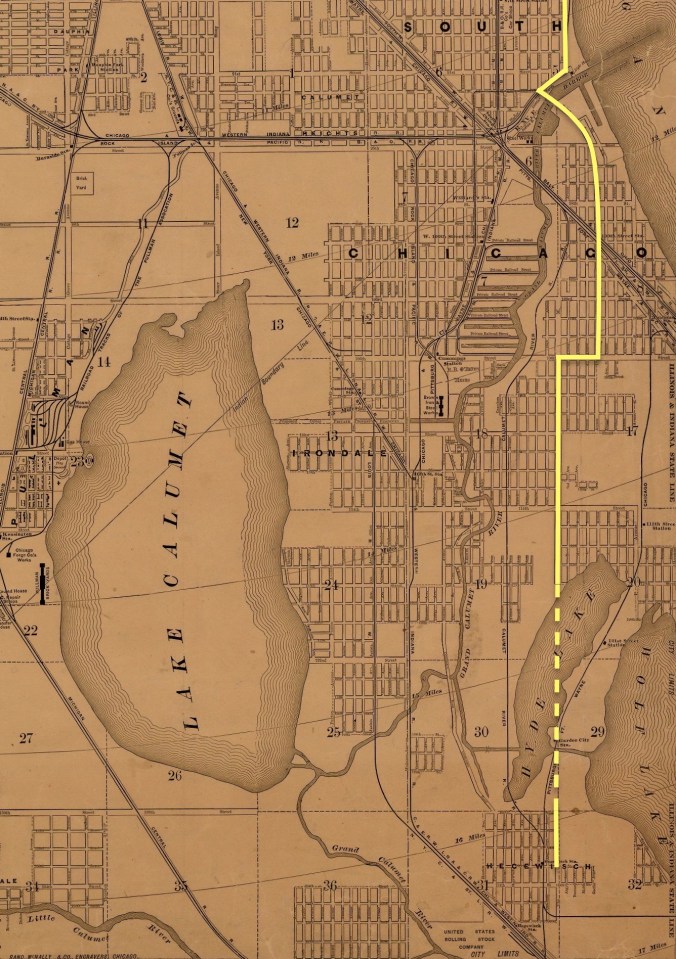

There’s a bit of curve around 126th Street that you notice when driving the route, but the bottom two-thirds of yellow line provides a rough idea of today’s current Avenue O.

General Route of Today’s Avenue O. Source: Rand McNally’s Standard Map of Chicago, 1892. Map Collection – University of Chicago Library.

But the glow from the Indiana Tollway as well as heavily polluting factories and refineries from the other side of Wolf Lake reminded us of how tainted the environment of the Calumet Region has become in just a relatively short century and a half. There are large slag heaps over just to the west of Avenue O, too, where Republic steel used to dump its waste. Many on the Southeast Side are working to restore and appreciate the natural ecosystem. While the days of industry in Southeast Chicago have left a major imprint on the region’s identify, in the great scheme of things, the days of steel may just be a blip.

Then after miles and miles we traveled from the North Side (and what seemed like many more). . .small, tidy homes appeared, one after another.

We made it. Hegewisch was real.

And we were quickly reminded why we had been looking for this place for so long. Honestly, though, if had not carefully planned out our route or made a wrong turn, we may not have found Hegewisch this time at all.

We turned right on 133rd Street, right after Pucci’s, a place that in retrospect, did more for us to wonder about pizza and history throughout the city than any other thing. It is also a place, we would learn much later, that would help connect the history of pizza in Hegewisch to its present. If we remember correctly, it was still open on one of our first visits to the neighborhood. Sadly, by the time of our official pizza trip, Pucci’s had been shuttered for good. Perhaps two locations were unsustainable in the area. Its closure served as a subtle reminder that parts of the Southeast Side had been open for business, often thriving under the industrialized economy of the twentieth century. They had held on for so long, in many cases years after many large industries had left or closed. Then, with little fanfare, they slowly faded away.

Just like in other parts of the city, we saw lines of houses on a strict grid and the occasional Chicago Transit Authority bus stop sign. But when we crossed those railroad tracks, it was like entering Small Town, America circa 1950.

Those little idiosyncrasies make the history and character of Hegewisch unique enough to be worthy of a closer look.

✶ ✶ ✶ ✶

The history of human settlement in and around the area of present-day Hegewisch is relatively short. It was only a thousand years ago that Lake Michigan receded from the area, leaving wetlands that were used for hunting, fishing, and trade routes by American Indians of the Potawatomi nation. Some have suggested that Father Jacques Marquette actually camped between the Grand Calumet and Little Calumet rivers at Hegewisch in the winter of 1674-75 rather than doing so on the portage between the Chicago and Des Plaines Rivers (the exact location, however, remains a matter of debate). The Potawatomi left the area in large numbers after the signing of the Treaty of Chicago in 1833. Around the same time, Chicago, then a small village, incorporated as a town then as a city a few years later. Its subsequent growth led to the incorporation of surrounding areas, including the town of Hyde Park, which included the not-yet-founded area of Hegewisch, in the 1860s. As recalled by Henrietta Gibson, her father, David Combs purchased an inn and a farm in the early 1850s along a stagecoach line in Hyde Park’s far southeast corner. Well into the 1850s, she recalled a playing with Potawatomi children in the area. Later in that decade, rail companies looking to connect various cities to the growing Chicago market used immigrant labor to construct railroads through the area, setting the stage for the area’s development in the coming century and a half.

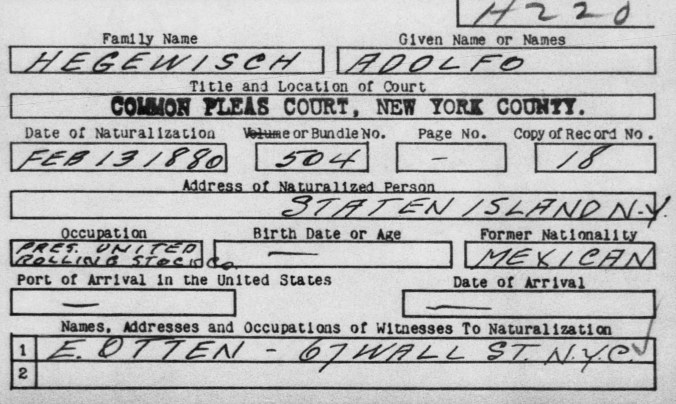

Recognizing the advantages of the natural waterways and the opportunities offered by rail lines in Southeast Chicago, a number of heavy industries built factories in the area. One of the them was the United States Rolling Stock Co., a railroad car manufacturing firm. In 1883, Adolph Hegewisch, president of the company, commissioned the purchase of land in the far southeast corner of the Hyde Park township right at the Indiana border that included the Combs farm. There, at the meeting point of railroads a new car factory was built, replacing the company’s factory located on Chicago’s Lower West Side at Blue Island and Robey (now Damen) Avenues (the factory’s location is often erroneously listed as Blue Island, Illinois). He envisioned a town that would be a regional center of industry.

The car works for the United States Rolling Stock Co. were planned clearly before their construction. Wood-working, erecting, and painting shops, as well as a car truck shop, a blacksmith shop, an engine repair shop, and a machine shop, where iron work was done, were each important facets of the factory. Various cranes, pits, lathes, furnaces, and specialized machines were used throughout the works, and rail lines connected different shops. There was also a foundry divided into three sections: a wheel foundry, a general foundry, and a brass foundry. The U.S. Rolling Stock facilities also included offices and a drafting rooms. Thus, the factory provided numerous opportunities for different types of work for those with specialized skills and for those who possessed no prior experience whatsoever alike.

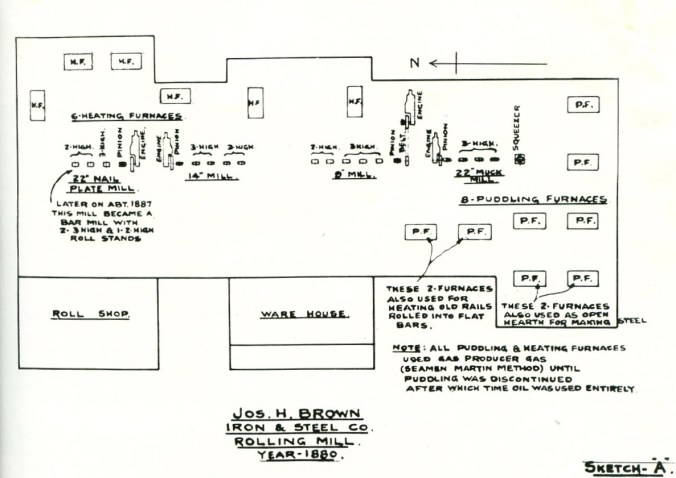

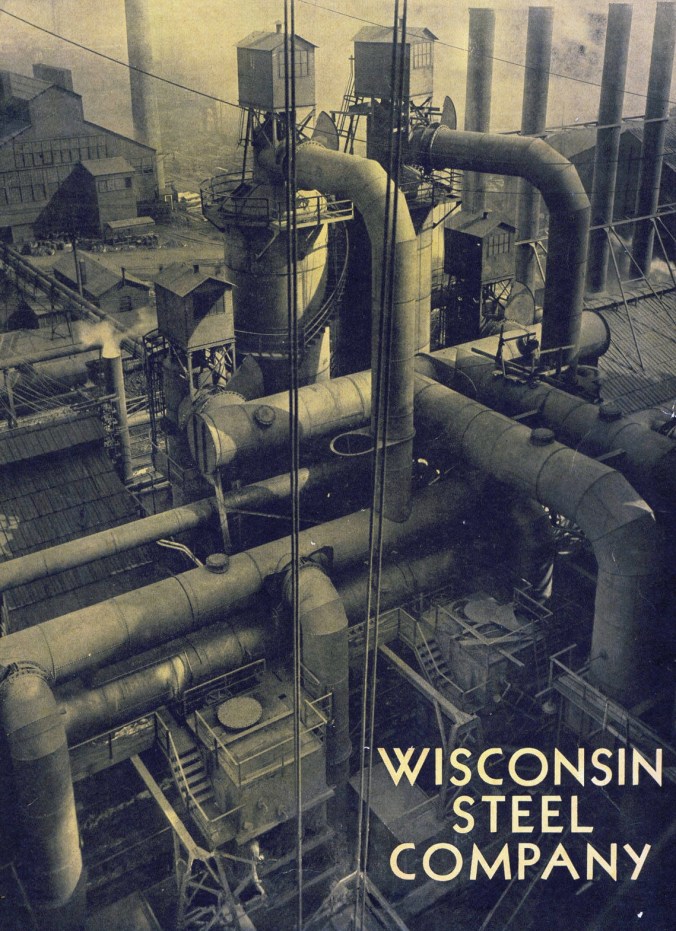

Just eight years earlier, in 1875, Joseph Brown built the first heavy industry, a steel mill about four miles north of the Rolling Stock Co. works.

Source: Wisconsin Sparks, June 1947. Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

Brown’s mill eventually evolved into Wisconsin Steel, one of the most important employers in the region.

Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

Other large industries soon followed, particularly more steel mills.

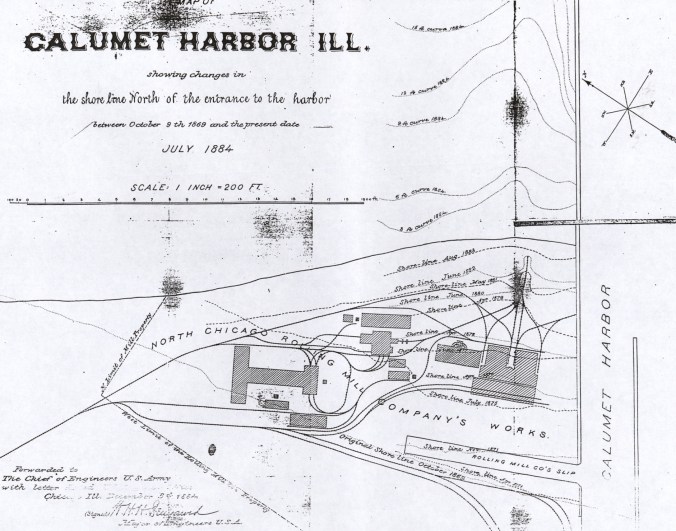

In 1880, the North Chicago Rolling Mill Co. built their South Works steel mill in South Chicago along Lake Michigan north of the mouth of the Calumet River.

Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

The South Works mill became the largest employer in Southeast Chicago, and was later owned by Illinois Steel, then Carnegie-Illinois Steel, and finally U.S. Steel.

North Chicago Rolling Mill South Works Blast Furnaces. Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

More steel mills and foundries would be built in the next few decades, including Grand Crossing Tack Co., the future Republic Steel. Iroquois Furnace Co., later Iroquois Steel, and Youngstown Sheet & Tube after that, opened a facility in South Chicago in the 1890s, as well.

Iroquois Smelter, South Chicago, 1901. Source: Library of Congress.

Industrialists also built mills across the state line, including Inland Steel in East Chicago and, by the early 1900s, U.S. Steel‘s Indiana Steel, or Gary Works. The region surrounding Hegewisch and the Rolling Stock factory showed signed of becoming an industrial center, where hard, dangerous labor was a way of life.

Worker at Illinois Steel, c.1890. Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

Many of the factory’s workers were immigrants who came to Hegewisch to build a better life for themselves. Recognizing an opportunity to provide workforce stability for his factory and profit on real estate, Adolph Hegewisch purchased acreage north of the factory site with the intention to build and sell houses to his factory workers, which he predicted to be numbered in the thousands. Thus, Adolph (sometimes listed as Achilles) Hegewisch’s subsequent namesake town intentionally rose from the Calumet marshes as a workers’ community in the vein of the nearby–and more famous–Pullman. Unlike Pullman, where the Pullman Car Company exerted tight control over local housing, workers in Hegewisch typically owned their homes.

Adolph Hegewisch’s Hegewisch Land Co. tasked the real estate firm of Bogue & Hoyt, with the physical development of the Hegewisch community. Bogue & Hoyt was previously responsible for subdivisions in the Kenwood and Woodlawn sections of the Hyde Park Township, and, later, another industrial subdivision near the Grant Locomotive Works in Cicero. Preparing for service-sector economic development that would accompany new workers and residents, South Chicago Avenue, the main commercial street in the newly-platted community, would be paved at no cost to new home buyers.

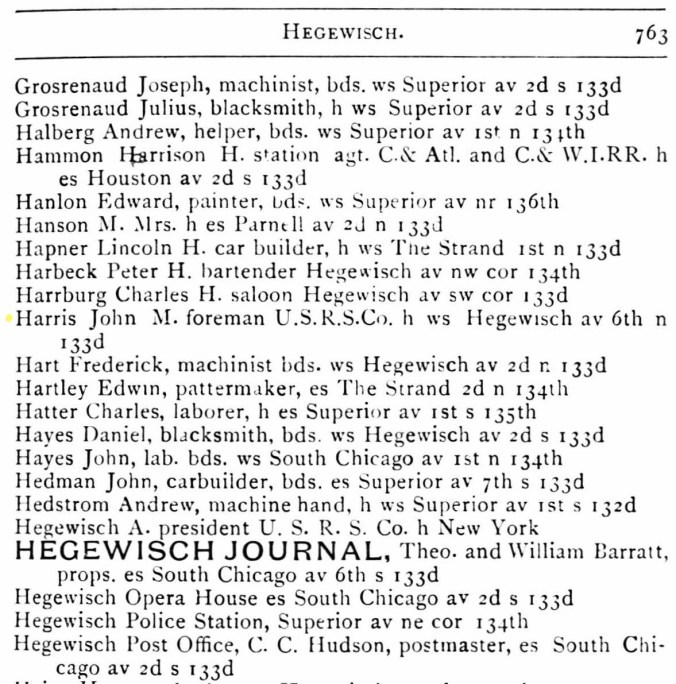

Many of the earliest lot owners came from other parts of Chicago, and some stayed for the rest of their lives. The first lot owner in the Hegewisch plat, John Harris, moved to the section from Pullman when the area was mostly swampland. Harris and his wife reportedly often tied their daughter, Irene Harris Frishkorn, the first child born in the community, to a tree with a rope so she would not get lost the marshy wilderness. Harris, who was listed in early directories, lived in the community until he was 84 years old. (Hammond Times, January 5, 1940) Still, some residents moved in and out of Hegewisch relatively quickly, not showing Harris’s lifelong commitment to the town. Adolph Hegewisch did not, however, live locally. Instead, he called New York home, a fact that fit with the local community’s ideal as a perfect home for the common workingman.

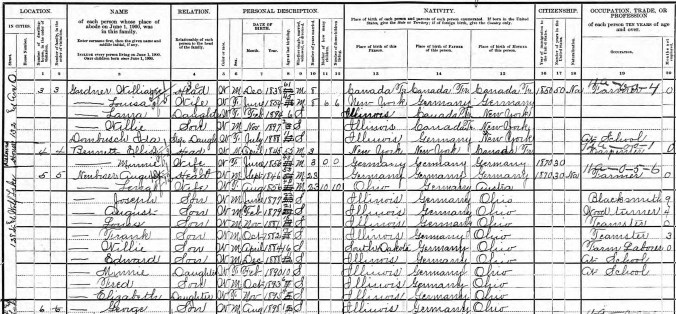

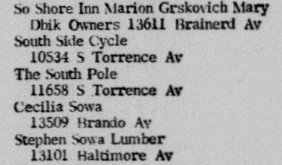

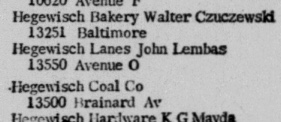

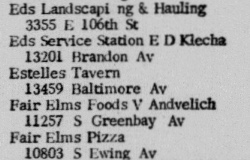

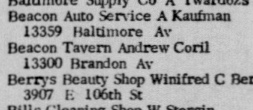

Source: The Hyde Park Directory, 1889. R.R. Donnelly & Sons, Chicago.

Many of the street names listed in the 1889 directory changed in the following decades. Superior is now Burley Avenue. Hegewisch Avenue became Ontario and, later, Brandon. South Chicago Avenue, after a few years as Erie Avenue, received its current name, Baltimore Avenue, in 1913. The Strand referred to the entry to Hegewisch for Ernie and me, today’s Avenue O.

U.S. Rolling Stock Co. located south just across railroad tracks. Source: Rand McNally’s Standard Map of Chicago, 1892. Map Collection – University of Chicago Library.

Settlers in the late 19th century came from many countries, and included many German, Irish, and Swedish residents, with each group building or supporting churches. Germans founded Trinity Lutheran Church at 132nd and today’s Burley Avenue in 1887. St. Columba was founded in 1884 as territorial Catholic parish that was often associated with the Irish Catholic community. Local Swedes founded Lebanon Lutheran in 1896. Hegewisch also included Poles, Serbs, Slovaks, Croats, Czechs, and among others. Despite the diversity of new residents coming mostly from Europe, the community failed to reach Adolph Hegewisch’s population projection of 10,000 people within two years, and his dreams of constructing two grand canals never materialized.

The U.S. Rolling Stock Co., through some headache-inducing corporate ins and outs due in part the Hegewisch factory’s initially unspectacular business performance, was purchased in the early 1900s by the Western Steel Car Company, a subsidiary of the Pittsburgh-based Pressed Steel Car Co. Keeping the names straight can get pretty exhausting, though one researcher, Eric A. Neubauer, has managed to sort it out. Nonetheless for decades the car factory located on the southwestern edge of Hegewisch between Howard (later Brainard) Avenue and the Calumet River and later known simply as Pressed Steel provided jobs in one form or another for thousands of local residents and helped define the culture of the community.

In 1889, just six years after the founding of the town, the huge, rapidly growing city of Chicago annexed the Hyde Park Township, which included the very young and quiet community of Hegewisch.

Hegewisch annexed as part of the Hyde Park Township, at bottom right in yellow. Source: Map of Chicago Showing Growth of the City by Annexations. Map Collection – University of Chicago Library.

Without the factory, the Hegewisch likely would not have been founded, making the town’s orderly development seemingly a secondary concern at first. But soon enough residents of Hegewisch demanded better services, especially after the town was annexed by Chicago. They felt particularly neglected by the city at the same time the neighborhood was experiencing economic success in the early 1900s. The community, just as today, was rarely recognized. Most Chicagoans did not know where it was nor had ever heard of it, so why should they do anything to help it?

The remoteness of Hegewisch was a common theme expressed by residents and observers of the community. One reporter’s description of arriving in Hegewisch in 1905 highlighted the mystery and eventual second guessing that occurred while traveling to the area located so far from busy, densely-populated central Chicago and bustling surrounding neighborhoods. “When the train finally leaves the Englewood station the passenger knows he is really on the way to Hegewisch.” Englewood itself was several miles from downtown. To get to Hegewisch, one had to travel much farther south. “Glimpses of pretty suburbs, clubhouses, and spacious training grounds claim his attention as the train gathers speed,” continued the reporter. “Great manufacturing establishments pass before his vision on either side, and the train is at last on the open country. On both sides of the tracks in the ditches formed by the overflow of Calumet lake hundreds of mud turtles are sunning themselves on logs in a dreamy manner. Just as the passenger is beginning to wonder if by any chance he is one the wrong train, or has been carried beyond his station, the train stops, two people get off and make for the nearest saloon.” (The Inter Ocean, September 17, 1905)

“This is Hegewisch.”

While that description may have been written over 110 years ago, we found that it can still be remarkably accurate. As the reporter notes, a local “gazes with curiosity at the pilgrim from the city and goes to sleep again.” We’ve encountered that look a few times! So, Hegewisch changes. But it also does not.

Those that came to work and live there, like John Harris, often stayed for a lifetime. Visitors, like the reporter, only stayed only briefly.

That reporter may have never made his brief visit to the community had it not been for a local resident who had “put it on the map.”

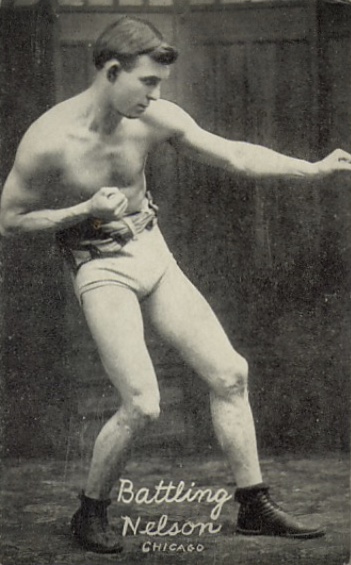

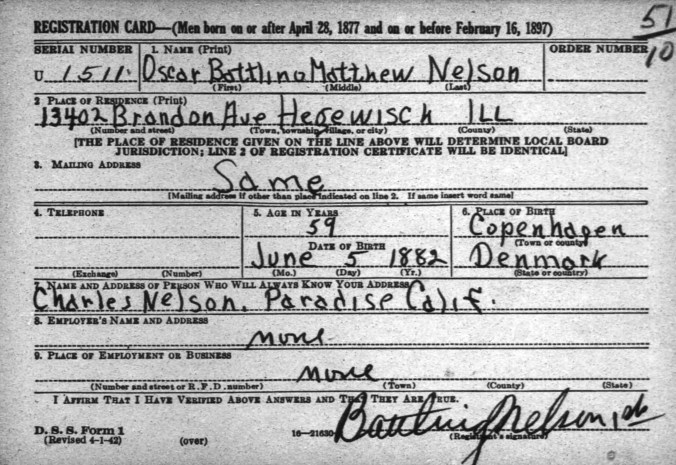

That resident–by far the most well-known early resident of Hegewisch–was light heavyweight boxing champion Oscar Nielson, famously known as Battling Nelson.

A Danish immigrant born in 1882 who came to Hegewisch after a stop in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, Nelson worked cutting lake ice as a boy, and later as a meat cutter at George H. Hammond Meat Packing Co. across the state line in that company’s namesake community, Hammond. He achieved initial fame after defeating a seemingly-unbeatable opponent in circus sideshow and quickly became one of the fiercest–most famous–fighters in America. His thrilling adventures across the country were followed closely by the press, with reporters often highlighting his home base, Hegewisch.

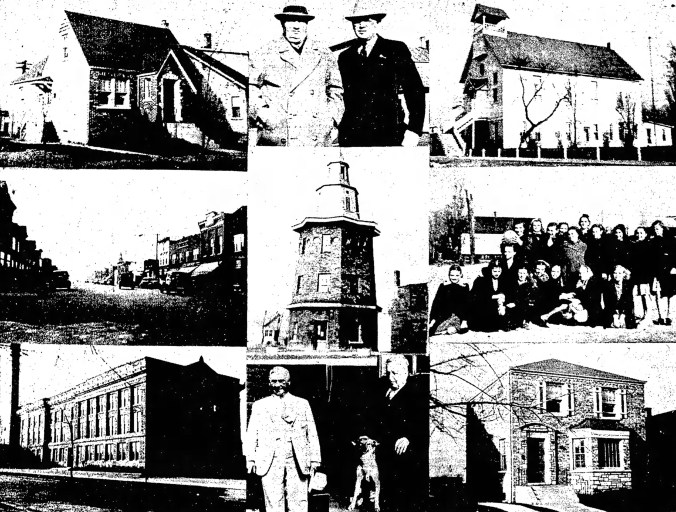

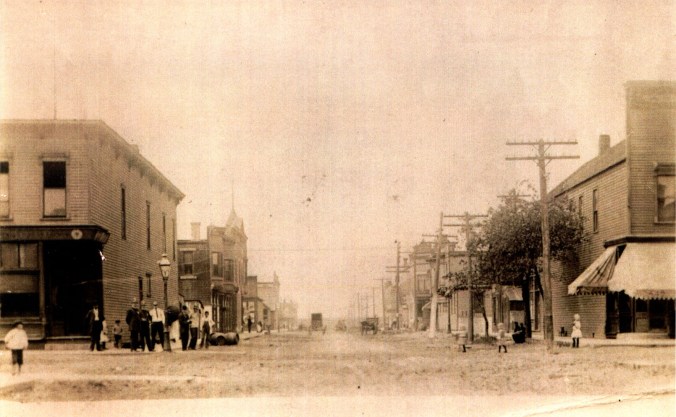

Postcard view of Hegewisch circa 1900. Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

Throughout regular articles detailing his exploits, the press–locally and nationally–repeatedly referred to Hegewisch as “Hegewisch, Ill.” In his autobiography published in 1908, Nelson highlighted–and even exaggerated–early outsider impressions of Hegewisch that have persisted. “In fact I was togged up like a real fighter, even though I was an unknown and from a place called Hegewisch, Ill.,” Bat, as he was often called, wrote of an early fight in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. “‘Hegewisch, Illinois!’ exclaimed the Master of Ceremonies. ‘Where in the world is that located?'” Nelson even published his book in Hegewisch, Ill., not Chicago. (Two thorough books detail Nelson’s career and connection to Hegewisch: The Nelson-Wolgast Fight and the San Francisco Boxing Scene, 1900-1914 by Arne K. Lang and Battling Nelson, the Durable Dane: World Lightweight Champion, 1882-1954 by Mark Allen Baker.)

Source: Lake County TImes July 6, 1908.

Hegewisch stood above all Nelson’s other geographic connections–be it Oshkosh, his first home in America; Hammond, where he previously earned a living; the numerous towns across the country he visited as a fighter; or even his native Denmark–in shaping is personal identity. As Nelson writes in his autobiography, “Enthusiastic writers have been wont to call me “the PEERLESS DANE,” “the DURABLE DANE,” etc.” But jettisoning his ethnic heritage in favor local loyalty and fame, he writes, “This is all very nice, but I am simply Battling Nelson, of Hegewisch, Illinois, a champion boxer, that’s all.”

Hegewisch may have been known for the construction of rail cars–and now for its famous son–but greater acclaim seems to have stuck with another car-producing town, nearby Pullman. The histories of Hegewisch and Pullman are linked not only by that common industry but also the ambitions of their respective founders. Both towns were intended to perfect the company town concept. Despite the company’s mutual long work days and the fact that the Calumet River, marshland, and the sizable Lake Calumet created significant travel barriers, there apparently was some degree of common interaction, and even rivalries, between the two blue-collar communities. Shop and club teams competed against one another, as they did other with teams based in industries across the region, in sports such as baseball and football. For instance, baseball teams from various foundries and and mills competed in the Inter-City Industrial League.

Source: Lake County Times, May 15, 1917.

An incident in 1902 highlighted connections and tensions between the two communities, both of which were by then remote neighborhoods of Chicago. Nelson was apparently about to put fighting behind him–even telling his father he would strongly consider quitting–but neighborhood pride got in the way during a night out on the town with friends. As he tells it, “The crowd usually hangs out at Dad Knight’s bar.” According to his mother, he never smoked or drank, and was more interested in investing his earnings than having fun. But if he wanted to socialize, avoiding taverns altogether was likely quite difficult. “Just as we went in the door two fellows were having an argument. One of them was from Pullman, where they make the sleeping cars. In Hegewisch we have the largest car works in the world, but we only make working cars, such as flat cars, freight cars, etc.” Were there perceived class differences between the Pullman and Hegewisch communities? Workers in Pullman made “palace cars,” after all. “The Pullman fellows think they have something on us because they make fancy cars, and there is always an argument about which is the better town.”

Despite this recollection, we’re not really sure how in 1902 a guy from Pullman ended up in a Hegewisch tavern without some effort. This map from 1897 shows the aforementioned barriers, and no direct rail line between the communities, much less a passenger one. Streets only provided a roundabout route, and many of them weren’t in passable shape. The lake, years before major dredging operations there, was relatively shallow, possibly allowing for boat travel, but that would only take a person part of the way. Nelson described Pullman as “just six miles away,” but it may as well have been much farther.

Source: New Map of Chicago Showing Location of Schools, Street Car Lines in Colors and Street Numbers in Even Hundreds, 1897. Map Collection – University of Chicago Library.

A map from 1904 (not shown) didn’t show an easy connection, either, but by at least 1912, the Chicago Lake Shore line crossed the marshes and Calumet River. That was about a decade after Nelson’s fight in Pullman, though.

Source: Map Showing Railway Transportation Conditions, 1911, Map Collection – University of Chicago Library.

Also in 1902, McCormick and Deering reaper company merged with three other firms to create International Harvester. Meanwhile, that same year, International Harvester took over Joseph H. Brown’s original steel mill north of Hegewisch in Irondale (which had previously changed hands a few times), and began producing steel exclusively for the company’s factories, including the one in West Pullman that employed about 1,400 workers. Many residents of Hegewisch would work at the mill, now named Wisconsin Steel, and create somewhat of symbiotic relationship between the two areas on opposite sides of Lake Calumet.

Some residents of the Pullman/West Pullman/Roseland area were connected to Hegewisch through work. During his days as a football star, Minnie LaForest lived the Pullman area and played for the Pullman Thorns, among other teams, in the first two decades of the twentieth century, but he worked at Western Steel in Hegewisch. And some who lived in Hegewisch worked elsewhere in the region, including for the Pullman Company. For instance, a different, younger Oscar Nielsen from Hegewisch (also of Danish descent) worked for the Pullman Company at the beginning of World War I.

So despite the physical travel barriers, the communities were at least aware of one another, and movement between them did occur, even if, in 1902, interaction was a little less common than just a decade later. “‘Maybe you do make the best cars,’ said the fellow from Hegewisch, ‘but you can’t fight over there,'” Nelson writes. Quickly, the argument escalated and soon a fight was scheduled between Bat and a fighter from Pullman named Frank Colifer. Bat’s father, who had once opposed his son fighting, got worked up and fully supported his son taking on the fight.

“I had to fight for the honor of Hegewisch, and the fellow who was boosting me patted me on the shoulder and said: ‘Now bring on your fancy Pullman fighter!'” Fancy, huh? A jab at one’s masculinity, or was this another instance highlighting subtle class distinctions being made between the two communities? At a crowded barn next to a saloon in West Pullman, the fight commenced. Workers from Pullman cheered for their man, and all the workers from Hegewisch–the now-united “Danes and Swedes” who populated much of Hegewisch at the time and were reportedly often at odds with one another–pulled for Nelson. As Nelson punched his way to victory, “the Hegewisch crowd was crazy with joy.” Pullman, in this instance, may have been silenced. So far, though, that community is winning the battle of historical recognition, first as a Chicago historic district, then as a state historic site, and most recently as a national monument. Hegewisch has none of those distinctions.

Just a year after the publication of his autobiography, Nelson again created a bit of controversy when a teacher invited him to a West Pullman school to speak. The invitation came from the school’s principal, who had previously taught Nelson at Henry Clay School in Hegewisch. The principal, however, did not inform the superintendent and school board president, both whom were shocked by the prospect that a pugilist could be directly influencing impressionable children, possibly causing an outbreak of fistfights. Despite their fears, Nelson reportedly recommended that the children learn to box but they should not bully others, and they definitely should not pursue the sport as a career. “And don’t smoke, chew or drink if you want to grow strong and keep healthy,” Nelson said to the children. “Take lots of exercise, too, and whatever you do, try and be the best at it.” With this motivational language, one can only wonder how Nelson would have been received had he been a hero of Pullman instead of Hegewisch.

Source: Lake County Times – November 2, 1909.

Just a few years later, Hegewisch and Pullman began playing one another in football. Eventually, their interaction was so common that they were once accused of conspiring with one another to beat the rival East Chicago Gophers, one of the league’s standout teams. An accusation was made that the Hegewisch team was “loaded” with five players from the Pullman team to beat the mighty Gophers, who had completed a number of recent seasons undefeated. The offended Hegewisch coach refuted the claims somewhat, stating that two of the replacements did indeed play for the Pullman team, but they were only added because two players for Hegewisch were out sick or injured. As for the three other accused players, they did not belong to the Pullman team and had not played for the Pullman team. . .that year. “[A]ltho,” manager Joseph Powell wroted, “they all played with that team last year,” and have been permanent members of the Hegewisch team for the entire current season. In this instance, the two car company towns were sticking together.

Most articles written about Hegewisch during its first three decades of as a town repeated common themes, some of which linger today. One common theme expressed by both residents and outsiders who visited was the dichotomy of a community moving both upward and nowhere at all at the same time. Hegewisch was an established settlement with a large factory and locally-based workforce, but by the early twentieth century it had had a hard time attracting the same type of investment seen after the building of the Adolph Hegewisch’s facility. Other factories did not immediately follow the founding industry to the town as had been predicted, resulting in population levels that failed to meet his original expectations. This slow growth likely did little to attract the attention of Chicago lawmakers, and as the town instead grew slowly, conditions of the former wetlands improved even slower. “Hegewisch has been patient for twenty-three years, which is about the length of time the town has been in being. At that time the great railroad car shops were built, which gave the town an excuse for existing, and started the advance guard of building and loan associations on their preliminary raid. They did with Hegewisch that which has happened to many embryo towns.” (Inter Ocean, September 17, 1905)

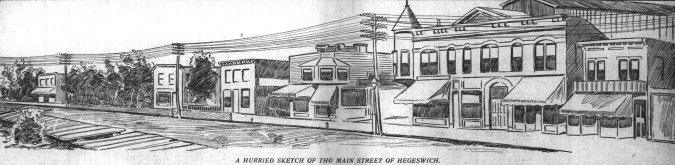

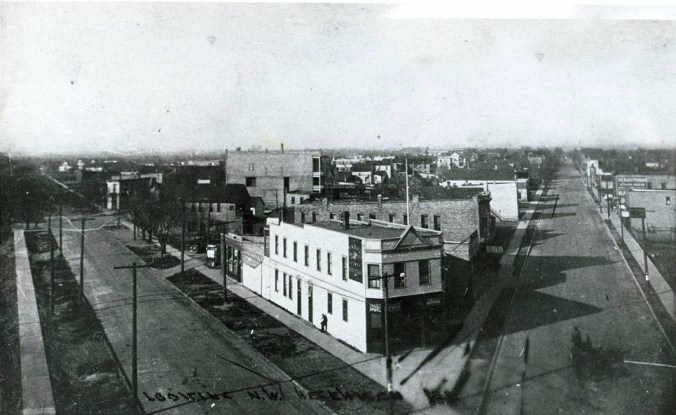

“Bird’s eye view of Hegewisch.” Source: The Inter Ocean, September 17, 1905.

A number of houses were quickly built to meet the high demand, but services and amenities that would make the community livable were of secondary concern. “Homes purchasable on on the installment plans sprung up by hundreds and were disposed of to the thrifty mill operatives. A few wooden sidewalks were built, and are there today. The roadbeds were slightly elevated, leaving plenty of space beside the walks for the waters of Calumet lake, the river, and other bodies of water as an overflow.” Due to this water, ducks “have since become domesticated, the hundreds of ducks which dwell contentedly adjacent to and beneath the sidewalks seem to be part of the town. Swimming gracefully up and down or floating with the gentle current they are at peace.” There are a few large trees, too.

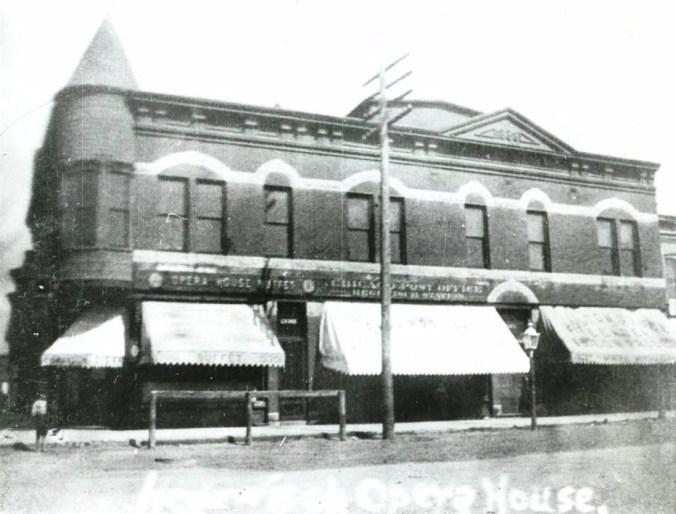

Sidewalks were still made of planks and the streets were unpaved, but 22 years after Hegewisch was founded, things were looking up. In 1905, as has been the case throughout Hegewisch’s existence, “[the] modest cottages of the inhabitants are fairly well kept up.” Bat Nelson was buying up real estate with his earnings, too, and local businessmen were “planning to take advantage of the sudden fame of the town,” with a huge celebration in Nelson’s honor. Furthermore, “according to reports, there is now more building going on in the the town than in the past fifteen years.” The $10,000 department store being built across from the opera house probably may have had more to do with national economic trends–the panics of the 1890s were over–but no doubt many residents connected Nelson’s success to the success of Hegewisch.

Source: The Inter Ocean, September 17, 1905.

At this time, about 4,600 people lived in Hegewisch, with most men working in the local factories. Western Car and Foundry employed about 1,500 people, while another car plant, the Northwestern Car & Locomotive Company, employed a smaller, but still large number of people. The General Chemical Company, a producer of sulfuric acid that was located on today’s Carondolet Avenue north of Hegewisch at the Calumet River, employed a large number of people, as well.

But despite the economic turnaround, they just couldn’t get Chicago’s city hall to pay any attention. “‘The trouble here is,’ said E.M. Skinner, a well known grocer, ‘that the city has never done anything for our streets, and it doesn’t make any difference what administration is in, we don’t cast enough votes to make it an object of the city to do anything to fix up the town. The people here are prosperous, but we can’t get anything done, and that is the reason the town seems to be in such bad shape. It is not our fault.'” (The Inter Ocean, September 17, 1905)

Comprised of a population similar to a small town and with most of the labor force employed by local factories, the isolated Hegewisch was very quiet during most hours of the day in the early 1900s. And it was certainly far from a police officers’ haven that it would become in the mid-twentieth century. The patrol was so dull that some officers deemed it a punishment, while others stationed there enjoyed the quiet.

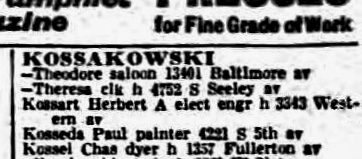

The old Hegewisch police station, located the northwest corner of 134th and Erie (today’s Baltimore Avenue), and torn down years later, fit the neighborhood well, as we would find out: it was a former saloon. It was often confused for one, too, which isn’t surprising considering there were reportedly 21 in the neighborhood at the time. The saloon’s old ice box had been converted into a storage facility for police records, and the old billiard hall was now a cell.

The force had a total of six individuals, each of which lived in Hegewisch with their families. It was a lonely job that included a lot of hanging around, with patrols spread out throughout the day. In 1905, just as over a century later, officers made very few arrests.. The Chicago Tribune even ran story entitled “Studies in Police ‘Still Life’ at Hegewisch, Where an Arrest Is an ‘Event.'”

Source: Chicago Tribune, January 29, 1905

Apparently, not much happened throughout the day. Hegewisch, “the dullest place in the world,” said a police lieutenant, was “so lonesome and you can still hear your hair grow.” These comments prompted another officer–one who had worked in Hegewisch for the last 19 years–to say “lonesome but good.” Those who knew Hegewisch best, defended it.

Despite being a curiosity to outsiders, some local thought the state of Hegewisch police department was unacceptable. A year and a half after the Tribune article was published, Nelson, increasingly active in local affairs, headed a committee of citizens that demanded that local Alderman Pat Moynihan work to give the neighborhood paved streets, electric streetlights, a street car system, improved school buildings, a clean water supply, incentives for new industries, and, as the article stated, “A real police station, with real policemen.” The tavern-turned-police station was yet another example of Hegewisch’s second class status.

Opinions expressed just a couple of years later confirmed the neighborhood’s disconnection with Chicago, especially how the city failed to fully provide Hegewisch with essential services. Even the town’s recent economic success had not improved day-to-day living conditions to a great extent. Contemporary reports highlighting squalid, dangerous, and unhealthful surroundings reflect Progressive era values, as does the urgent call to fix them. An article in the Lake County Times published August 20, 1907 pointedly addressed conditions in the town in true muckraking fashion, deriding local environmental conditions, the lack of services, and the apparent apathy and “total lack of public spirit” of the town’s citizenry. Deriding the local indifference, the article noted that eight of eleven people “were either unable or unwilling to inform a stranger as to the location of the postoffice.”

But, of course, they misspelled the town’s name. Or maybe it’s a “clever” pun?

Source: Lake County Times, August 20, 1907.

As the “beggar suburb of Chicago,” the article highlights the tension with it’s massive overlord. “The casual observer [. . .] would think the citizens of this community would rise up in their wrath and seceed [sic] from the city that has gobbled it up, sloughs, cinder roads, houses and all, and then set up an independent government. The average man would refuse to pay taxes to a city that neglected a portion of its citizens to the extent that Chicago neglects Hegewisch.”

Source: Lake County Times, August 20, 1907.

Sanitation was a critical issue. There were no sewers, too-prevalent water in sloughs was stagnant, and housewives dumped their dirty water in front of their houses, all of which contributed to an inescapable fly and mosquito problem.

Source: Lake County Times, August 20, 1907.

Despite making good wage, “[. . .] the average citizen of Hegewisch is putting up with conditions that are simply revolting.” The three to four thousand people of Hegewisch, the writer suggested, were so used to being neglected that many had “lapsed into a state of indifference from which it appears they will never recover.”

Source: Lake County Times, August 20, 1907.

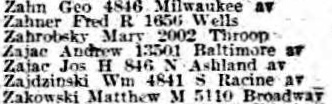

But, true to the spirit of Hegewisch would express throughout its history, saloons thrived. “[The] most prosperous places in the city are that saloons, and that with the exception of the department store, all of the best business blocks are occupied by saloons.” This last assertion can be confirmed by directory listings, as the five digit addresses of local taverns often ended with “00,” “01,” “58,” or “59,” the corner numbers. Two other defining features of Hegewisch’s historical character were evident, too: the concept of hard work and, previously noted by the police, the town’s sleepiness. “The men are all working. This is proven by the fact that the streets, which are practically deserted during working hours, are crowded with the employes [sic] of the big car shops soon after the whistle blows.” Hegewisch is a lot like that today. You notice a little more buzz around 4 or 5 p.m. when everybody gets off work for the day, then it gets quiet again as people head home.

Source: Lake County Times, August 20, 1907.

Despite its problems, the article served as an optimistic call to arms. “[In] spite of the fact that the town has been considered the end of the earth in Chicago [. . .] the town has forged ahead and is as prosperous as any city in the Calumet Region. New residences are being built, the streets are thronged with people, [and] the business houses are thriving [. . .]” the article continued. “Some day, however, there is to be a reckoning with Chicago.” Streets will be built up, predicted the writer, rail lines will connect to the central city, marshes will be drained, and the “city with its industries will be one of the manufacturing centers of the Calumet region, and Hegewisch, the beggar city, despised and shunned, will come into its own. The dreams of its one staunch friend, its favorite son, Batling Nelson, will come true.” Nelson wrote of his defeat of “Jack the Slugger” O’Neil in 1904 that, “I, of course, won the affair by a Hegewisch block, which means a mile.” Was he referring to the poor conditions of the Hegewisch streets? Business leaders hoped Battling Nelson’s success could change that.

Source: Lake County Times, August 20, 1907.

This boosterism likely did not hurt Nelson’s real estate interests in the community, either, as he acquired many local properties with his winnings, no doubt making him even more popular. In 1906, at the age of 24 , and reportedly already owning $30,000 worth of real estate in Hegewisch, he was elected president of the Hegewisch Businessmen’s Association. “Instead of undertaking to elevate the stage, or striving to become prominent in politics, he has devoted his attention strictly to the upbuilding of the material interests in Hegewisch.” He would fight for Hegewisch, and “he was only a lightweight, in a professional sense,” the article stated. “In a business sense he is the heaviest weight that Hegewisch cares to boast of at present, and he has already marked out a line of policy which stamps him as a far seeing promoter of those things which make for prosperity.” (The Inter Ocean, July 11, 1906)

Source: The Inter Ocean, September 17, 1905.

Nelson reportedly would “have maps printed showing Hegewisch as the great railway center of the Northwest, and upon which the name of Chicago will appear, if it be mentioned at all, in small letters. But his efforts will not be directed against the mother city, as the mother city is not really a rival of Hegewisch. We take it that Battling Nelson will devote himself to the task of crushing Gary in its infancy.”

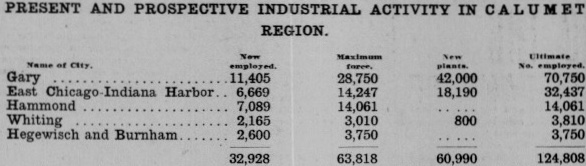

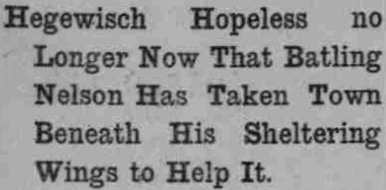

Source: Industrial Map of the Calumet Region of Indiana & Illinois, 1925. Indiana Historical Society.

Gary, a company town similar to Hegewisch, was reportedly projected by U.S. Steel to house 50,000 to 75,000 people, with the company’s Gary Works to be its central industry. “Yet it will be handicapped from the beginning, because Hegewisch is already on the ground,” the article stated. “Hegewisch is in Chicago, if only on the edge of it, and Hegewisch enjoys the advantage of water and rail communication sufficient to place it in the front rank of the world’s greatest industrial cities.” Not long ago, the article concluded, Hegewisch was known primarily as a duck hunting destination. But with Bat Nelson leading, “it is only in the dawn of its history.” Gary, however, would quickly take the lead, and by some measures, hold it for decades.

Source: Lake County Times, April 17, 1912.

Despite the article’s claim that Nelson did not have his eye on politics, it appears that he actually did to some degree, at least locally. In fact, just two years later, in 1908, he attempted to mount a campaign as a Republican to unseat Moynihan as one of alderman of the 8th ward. Likely not a coincidence, this move into local politics occurred in the same year that his Hegewisch-lauding autobiography was published.

Source: St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 29, 1908.

Nelson was popular, but Moynihan had supporters in the press, too. One cheerful article entitled “Here’s To Hegewisch” detailed how Hegewisch was “outgrowing its Cinderalla-hood.” The community soon would finally get modern improvements such as a sewer system and a new road connecting to Chicago thanks to the alderman. While it briefly noted Nelson, it claimed that “Alderman Moynihan seems to be the generally accredited philosopher, guide and friend of heretofore neglected Hegewisch. He is the fairy godmother who by a few waves of his wand has changed the gloom of the swampy settlement into a bright atmosphere of hope and pride.” (Lake County Times, November 1, 1907) After leaving the city council in 1909, Moynihan would effectively serve as the Republican boss of South Chicago and Eighth Ward and, after restructuring, the Tenth Ward into the 1920s.

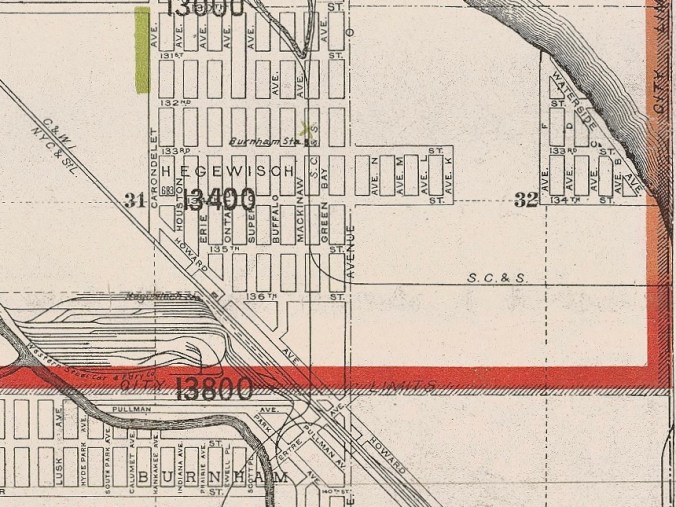

Hegewisch would get to keep its name, too, which it almost lost entirely when several railroad companies chose to name a local train depot “Burnham.” Offended by this effective removal of the town’s identity, Nelson himself wrote to Pennsylvania Railroad officials in protest. “If I advertised myself as coming from Burnham the big bugs across the pond would think I was a pink tea fighter,” he later stated. “Burnham is a soft name. It suggests mild blue eyes and yellow curls.” (Lake County Times, March 20, 1907) Eventually, the Hegewisch name that Nelson had fought so hard to champion returned in 1907, but the flippant attempt to remove the town’s civic identity likely put many residents on the defensive, helping create a sense of community but also a culture of suspicion of outsiders. The Burnham name appeared on maps as late as 1910, right in the middle of Hegewisch. In retrospect, Burnham seemed to at best draw a parallel between Western Steel and the other more famous car company, or at worst taunt Hegewisch by claiming the local car works for itself: one of the first streets just south of Hegewisch in Burnham was once named Pullman Avenue.

The Burnham station in the middle of Hegewisch, and Pullman Avenue in Burnham. Source: Rand McNally New Standard Map of Chicago, 1910. Map Collection – University of Chicago Library.

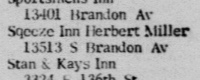

Nelson may have made the Hegewisch name famous, but Moynihan’s power and local customs likely kept the champion from mounting a successful campaign for the seat. It’s unclear to us whether or not he actually made it on the ballot. The local Republican ward bosses were also reportedly “perturbed” by his candidacy (St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Nov. 29, 1908). While he was very popular with many business owners, he may have faced opposition from everyday voters to his political stance against the ever-popular saloons that lined Hegewisch’s commercial streets and residential street corners. His platform stood for better schools, more factories and railroads, and improved services, such as the extension of the Chicago sewer system that perhaps Moynihan had yet to deliver. But by taking on taverns, an essential part of life in Hegewisch, he may have picked the wrong battle.

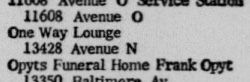

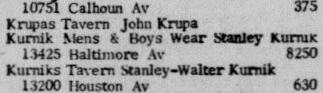

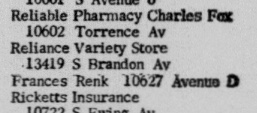

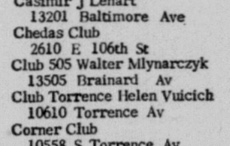

Decades later, in 1978, Barney Kurnik, then president of the Hegewisch Community Committee (and related to the former Kurnik’s Tavern?), lamented how things had changed in the prior decades. “‘There used to be taverns all over this place,’ mused Kurnik, ‘all over the street. Now maybe there’s 28 in the whole neighborhood.'” That said, we wonder if there were actually ever that many taverns in Hegewisch at one time. The 1905 Inter Ocean article about Nelson and Hegewisch claimed that there were 21 in the neighborhood. The 1917 city directory lists at least 16 taverns in Hegewisch. Businesses listed in the restaurant category, may have also qualified as taverns, increasing the number. If one added the taverns along or adjacent to Torrence Avenue in South Deering, the number would spike. A few taverns were located near the millgate at Republic Steel on Burley Avenue, as well. To confirm a number of 42 at one time might require a more thorough analysis.

Taverns are undoubtedly a part of the local culture and history. Their numbers were likely seen as a reflection of local industrial vitality: if industry was going well, then there were a lot of taverns, and if there were a lot of taverns, then industry must have been going well. Nelson and the anti-saloon folks were not only challenging social and cultural customs, many of which had been brought from workers’ countries of origin, but also indirectly threatened the community’s economic well-being. They are also–in discussions of the way things used to be–a part of the local working-class folklore.

Other political currents may have swept Nelson in a direction away from the aldermanic race, as well. One article passively stated that “Nelson had some thought of running for the city council in the Eighth Ward,” but the voices at a local mass meeting put him at the center of a brief secessionist movement. A mass meeting, held November 30, 1908–dubbed “Hegewisch’s independence day” at the “Faneuil hall of the Eighth Ward in an article the next day (Lake County Times, December 1, 1908)–in the town reportedly turned from discussion of the continued lack of services and disconnection from Chicago, to a vociferous call for politically leaving the city altogether and forming a new town.

Source: Lake County Times, December 1, 1908.

The people of Hegewisch had reached a “boiling point” and were tired of being “dragged down by the rest of Chicago.” The only way for Hegewisch to achieve its “city beautiful dreams” was to “cut loose” legally. “Chicago has never done anything for this part of the city,” Nelson said to the crowd. “We have no streets, no sidewalks, no sewers, and yet we pay heavy taxes. Let us separate from the city and form a city of our own.” Cheers of “Bat for mayor” and “Bat for us” came from the assembled crowd. “Mr. Nelson was visibly impressed with his becoming mayor,” the article noted, “and in a speech of some length that sounded suspiciously like chapter eighteen of his newest and first book, Mr. Nelson accepted the honors about to be thrust upon him.” A couple of photographs in his autobiography indeed showed him dappered up, possibly ready for a position of importance.

Hegewisch did not secede, and Nelson’s political ascent seemed to stall, particularly when his boxing career plateaued. And as much as he loved Hegewisch, he sometimes had a hard time getting people from out of town to love it as much as he did. For instance, his wife, Fay King, a famous cartoonist, was not impressed with the town at all. The tumultuous short marriage fell apart soon after the vows, which occurred at the Nelson family home in Hegewisch. Apparently, King had no interest in becoming the “queen of Hegewisch” and returned to her home in Denver. This site presents an excellent rundown of their courtship and marriage (if those words could be used to describe their connection), as well as their divorce, all based on newspaper accounts. Mark Allen Baker also details it in his biography of Nelson. He retired from fighting in 1920 and never seemed to reach the same level of popularity that he experienced a decade and a half earlier.

Nelson and Fay King in Hegewisch after their wedding. Source: The Day Book, January 25, 1913. Via Stripper’s Guide.

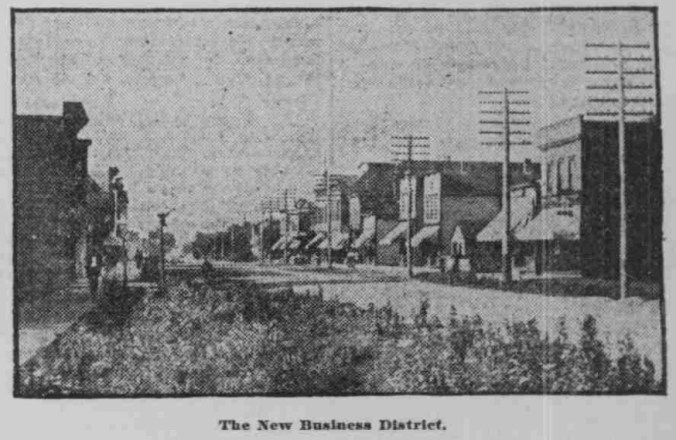

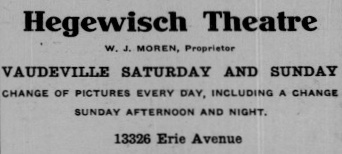

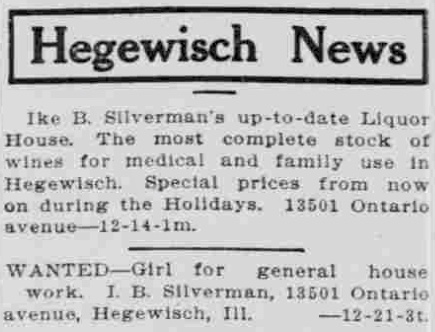

Hegewisch’s commercial districts became more sophisticated by the 1910s, as storefronts offering a variety of goods and services lined Erie and Ontario Avenues. Grocery markets, tailors, banks, clothing and dry goods stores, drugstores, restaurants, and, of course, taverns all served the working folks of the neighborhood.

Source: Lake County Times, March 2, 1912.

While Erie and Ontario avenues were becoming the primary commercial districts of Hegewisch, the Western Steel factory–the former U.S. Rolling Stock works–remained a focal point of of the community. Businesses, such as a hotel and several taverns clustered near it, each hustling for the workingman’s dollar. Barney Glinski’s restaurant was located on Howard Avenue (now Brainard) just steps from Western Steel.

Source: Lake County Times, April 6, 1912.

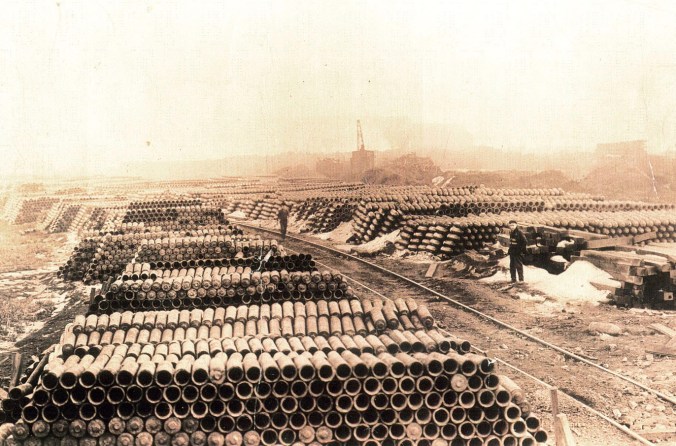

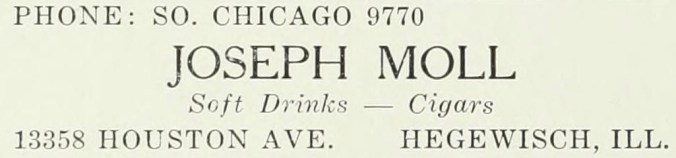

World events soon shifted the focus away from local issues, however. Following the American entry into World War I, residents of Hegewisch served in the armed forces, many seeing action in Europe. Meanwhile, work continued at the Western Steel factory.

Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

With the demand for explosive chemicals high, the General Chemical Co. delayed its expansion plans and, without compensation, turned over its patents and manufacturing processes to the federal government for ammunition production. Now in service of the war effort, large gun shells were produced in the Western Steel factory, as well.

Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

By October 1917, the Ryan Car Company, a car rebuilding company that had purchased and taken over the Northwestern Car & Locomotive Company works 1906, had begun hiring women to replace men lost to the military ranks. The initial group of 50 women included some native-born Americans, as well as Irish and Polish immigrants, and received a positive assessment from William M. Ryan, the company president. “They’re fine! Better than men!” he said.

Source: Life and Labor, October 1917.

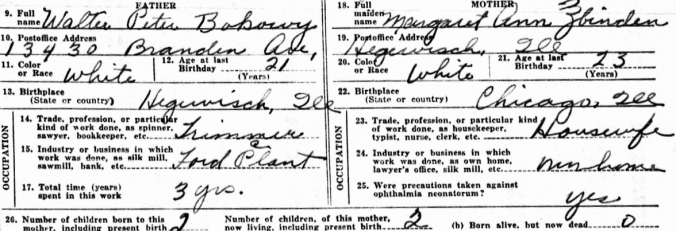

As primary employers, Western Steel and Ryan Car were both opportunities for stable work, as these two members of the Bokowy family, Jakel and Stanislaw, who came from Tymbark in Austrian Poland. These jobs could help provide them with a stable life and possibly business opportunities for subsequent generations.

The passage of the Immigration Act of 1917 just a few months earlier had placed literacy requirements on new immigrants, and substantially reduced the numbers of people entering the United States from Europe. Still, men from numerous countries in Europe had already entered the country prior to the restrictions and were employed in the Western Steel factory. With them, they brought different languages, religions, and customs.

Western Steel workers gather for a bond drive during World War I. Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

Despite this diversity, American loyalty was demanded during the war. As the sign notes in the center of the photograph–“Un-Americans are Hun-Americans”–many immigrants were placed under intense scrutiny regarding their nationalistic loyalties.

World War I bond rally on Baltimore Avenue at 133rd Street. Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

Tensions were high as anti-German through the country. Batting Nelson, having survived a bout with influenza and nearing the end of his fighting career, looked for new paths to relevancy and financial reward, trying unsuccessfully to sell his Nelson Dummy, a punching bag meant to look like the German Kaiser Wilhelm II, to the American military.

Source: The Ring, October 1990.

Even Adolph Hegewisch’s nephew, Adolfo Ernesto Hegewisch, a shipping agent based in New Orleans from Vera Cruz, Mexico, came under suspicion.

Source: City Directory for New Orleans, 1917.

An anonymous telegram suggested that Hegewisch and his family were secretly German sympathizers.

Source: Investigative Case Files of the Bureau of Investigation 1908-1922. National Archives.

Though the details remain unclear to us, the document even suggests he had some sort of connection to individuals behind the Zimmermann Telegram!

Source: Investigative Case Files of the Bureau of Investigation 1908-1922. National Archives.

A.E. Hegewisch, however, had defenders that vouched for his loyalty to the Allied cause, and the investigation into his affairs had few negative effects. As his uncle faded from public recognition–due in part the early financial troubles experienced by the U.S. Rolling Stock Co.–the related Hegewisch later rose to prominence promoting trade with Mexico.

Once the war was over in late 1918, demonstrated loyalty could prove important, particularly for immigrant factory workers with few, if any, business or favorable political connections.

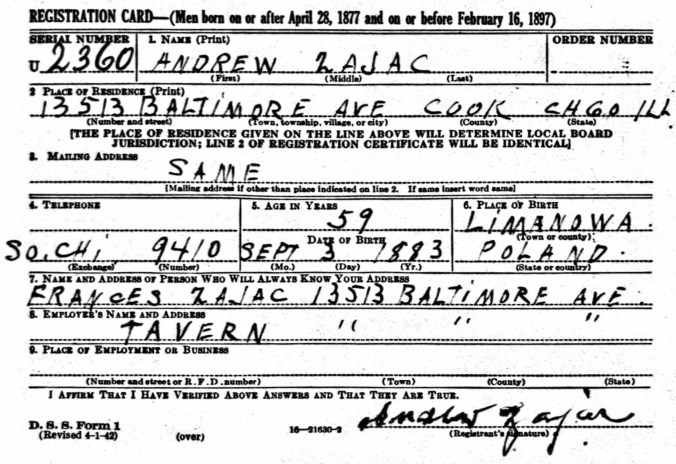

Armistice Day at Western Steel, 1918. Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

Successive laws restricted immigration more and more, stopping the flow of new members of the labor force to and from their home countries. Companies responded in part by sponsoring efforts to assimilate their workers to the American way of life. In one instance, about 100 men, most of which worked at Ryan Car Co., applied for citizenship under the direction of a local Methodist minister, including these men. The caption noted that many of the men “acquired the desire for citizenship while attending the Henry Clay school and the Fegber night school in Hegewisch,” perhaps due in part to the literacy requirements enacted in 1917. Further restrictions made into law in 1921 made meeting the requirements increasingly important, and, in particular, the Immigration Act of 1924, which would severely limit immigration from Eastern and Southern European countries, would make coming to the United States even harder.

Source: Chicago Tribune, February 27, 1922.

The Ryan Car Co. and Western Steel provided stable employment for many people in Hegewisch during and following the war, and even during the brief depression of 1920-21. Ryan employed fewer workers than Western, and the company’s regularly-run classified ad required a higher bar to reach for employment there: prior experience and one’s own tools. Western also looked for skilled workers, but working for the company could be a “good opportunity for men without experience to learn [the] foundry business.” Thus, at places like Western Steel and Ryan Car, a good job could be earned with some or no experience at all. And with hard work, one could possibly earn ticket to a better life for oneself and one’s family. That little American house–in Hegewisch–could get paid off.

But the price of stability could often go beyond hard work and long hours. Work in the car factories could be physically demanding and at times quite dangerous. Injuries were common. Newspapers routinely reported on accidents at the plants, including crushed hands, arms, and feet, resulting in amputations and even death. The Southeast Chicago steel mills, in particular, were so dangerous that different undertaking establishments fought for the lucrative business, locating their structures as close as possible to the mills to outmaneuver competing undertakers. Valley Mould & Iron, a company located 108th & the Calumet River that produced moulds for ingots used in steel production, was known as “Death Valley” because of the foundry’s dirty, smokey, and extremely dangerous working conditions.

The local steel mills provided grueling, though consistent, blue-collar work for residents for the next full century.

Source: Republic Reports, July 1950. Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

Mills across the Calumet Region in East Chicago, Gary, Chicago Heights, and Riverdale did so, as well.

Source: Riverdale Pointer, October 3, 1963.

They all helped define a local culture of hard physical labor, often in twelve-hour shifts, constantly surrounded by the industry’s by-products. Pollution ensured that everywhere one turned, they were reminded of steel. The rivers were increasingly dirty, the air often had a foul smell or was visibly polluted, and slag, a steel waste product, was heaped across the landscape.

Iroquois Steel Blast Furnace, 1918. Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

At the same time, one’s modest, yet comfortable house, yard, and street existed because industries like steel provided workers with the money to pay for them, as did numerous businesses, especially taverns, where workers could find some relief and build upon the social connections first forged by the mutually-shared stress and dangers of the mills. Accordingly, social and religious organizations thrived.

Wisconsin Steel blast furnace. Courtesy Southeast Chicago Historical Society.

The steel mills, in total, employed several thousands workers in any given year. By 1912, Western employed about 2,000 workers, Ryan employed 200, and General Chemical employed about 400 people. (Lake County Times, April 17, 1912) These numbers would fluxuate over the following decades, often reflecting nationwide economic trends, but all the while continuing to define Hegewisch as an industrial community where hard work stood at center of daily life. With few amenities and amusements outside of homegrown celebrations and ubiquitous taverns, workplaces like General Chemical Co., which became a division of Allied Chemical & Dye in the 1920s after a stock takeover, helped define local society and culture.

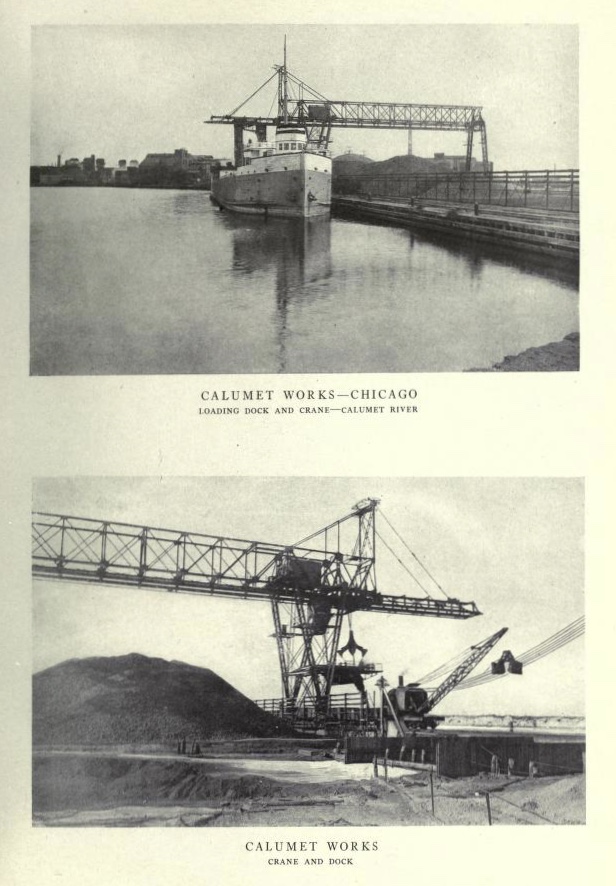

Scenes from the Calumet Works in Hegewisch c. 1919. Source: The General Chemical Company After Twenty Years, 1899-1919.

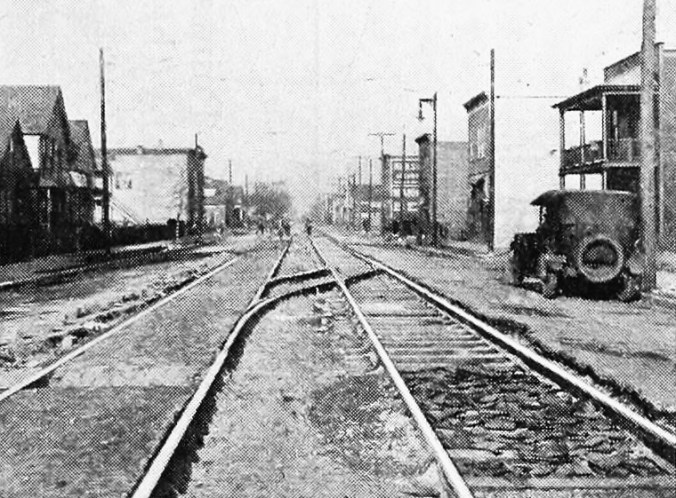

Street car lines finally connected Hegewisch to South Chicago–and the rest of Chicago–in 1918, making Hegewisch just a little less isolated. However, one technological advancement seen in the photo–the automobile–would eventually supplant the street lines as the most important mode of transportation in the neighborhood and across the country (and help Ernie and me get to Hegewisch).

Looking north on Brandon at Brainard – “(end of the line) at Pressed Street Car Works.” Source: Electric Railway Journal, January 4, 1919.

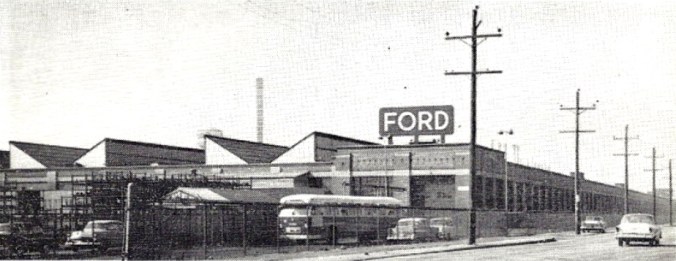

Another notable industry long-located in Hegewisch is the Ford Motor Company’s Torrence Avenue Assembly plant. The plant, more commonly known as the Chicago Assembly Plant, occupies a large tract in the northwest corner of Hegewisch, north of 130th Street and west of Torrence Avenue. Model Ts and Model As were produced there in the factory’s earliest days. Today it’s the Taurus and the Explorer. It has been a major employer in the region since it opened in 1924.

Source: CTA Transit News, September 1958. Illinois Railway Museum.

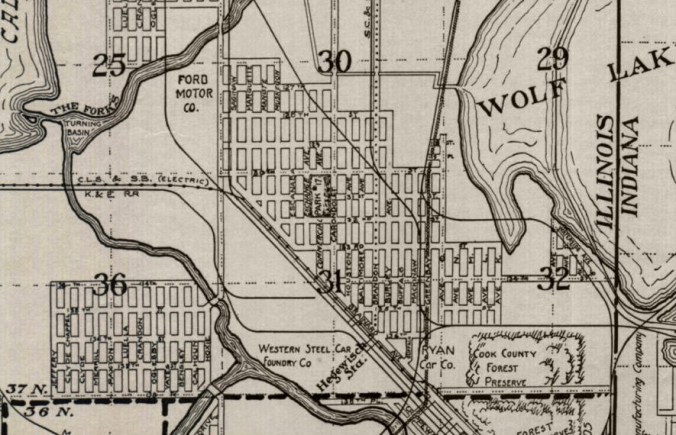

Right away, Ford had a strong presence in Hegewisch, bordering one large corner of the neighborhood. Hegewisch was surrounded by river, lakes, and marshes, but it was also flanked by industries.

Hegewisch on Industrial Map of the Calumet Region of Indiana & Illinois, 1925. Source: Indiana Historical Society.

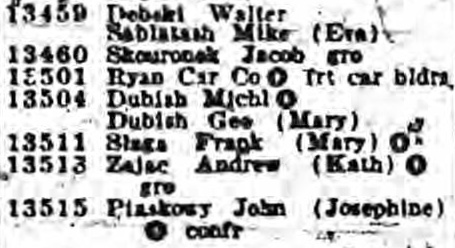

Tied to larger economic trends, industries in Southeast Chicago expanded as the American economy boomed. In 1925, Wisconsin Steel constructed a new merchant mill. To meet the demand, the car shops, the steel mills, and the Ford plant brought workers from all over the world, including various states in America. Census listings in 1930 from one hotel located at 13531 Baltimore Avenue showed a lot of men, all white, mostly in their 30s and single, from several states in the union, with a few men from other countries. Almost all listed “Car Shops” as place of employment, with some listing “Steel Mills,” “Automobile Plant,” and the railroad, while a few others were employed in the service industry or at General Chemical.

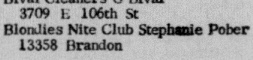

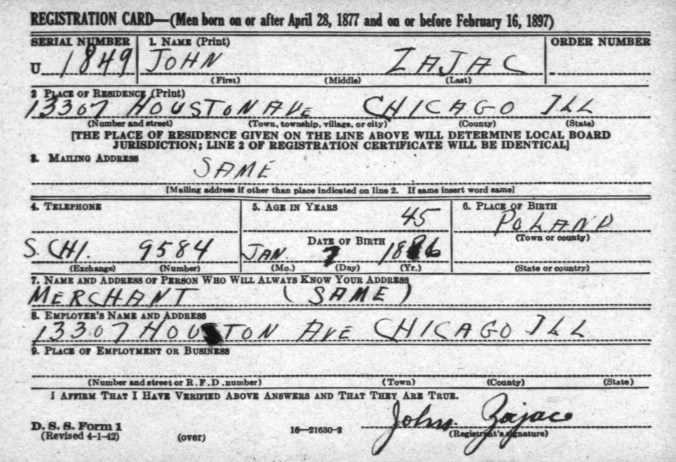

Hegewisch felt the effects of larger political trends as well. Joseph Moll opened a tavern here at 13358 Houston in 1911, but with the passage of the Volstead Act, Battling Nelson got his wish as the production and sale of alcohol was banned. Workers from places like Pressed Steel and the steel mills would have to find refreshment from something other than beer or liquor.

During Prohibition, tavern operators in Hegewisch either evolved or risked losing their businesses altogether. Many evolved into confectioneries or grocery stores. Moll’s replaced alcohol with soft drinks and cigars and later operated as a restaurant run by George Moll.

As pillars of local culture, taverns came back after Prohibition, but the industries that helped support them across the country were hit hard by the Great Depression and Hegewisch felt the effects. With growing competition from automobiles, Pressed Steel ceased rail car production in 1937. Labor tensions mounted, with the Little Steel Strike and the resulting violence at Republic Steel that same year. Ryan Car idled by the end of the decade. As many in the neighborhood searched elsewhere for work. South Deering actually grew by 1,764 residents, a gain of 18%, possibly due in part to Wisconsin Steel’s plans to expand in 1936. Furthermore, workers at Wisconsin Steel did not participate in the major strikes (they were represented not by the SWOC/USWA, but by the Progressive Steelworkers Union (PSWU)), and were often rewarded with same concessions gained by strikes at other plants. The other three Southeast Side neighborhoods, however, posted declines: the East Side lost 326 residents, or about 2% of its population, while the much larger South Chicago lost 1,593 people, or 2.8%. Hegewisch earned the distinction of losing the largest percentage of residents among Southeast Side neighborhoods with a net loss 381 people, or about 4.8%.

Government agencies such as the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps provided jobs to a number of people Hegewisch not employed by industries during the Depression. In fact, long-neglected local roads were finally improved (to varying degrees of quality) by the WPA, including 130th and 134th streets, each an access point to the neighborhood. Streets north of 132nd Street such as Escanaba, Muskegon, and possibly Burley were also paved by the WPA, as were the lettered Avenues in the western section of Hegewisch, including Avenue O. According to one local historian, the roads were comprised of slabs of asphalt with gravel along the edges instead of curbs. Without the federal government providing temporary employment for local residents, population losses may have been greater during the decade.

Even the beloved local real estate mogul Battling Nelson–“still the king of the people of Hegewisch”–felt the effects of the economic downturn. In 1938, at age 54, Nelson had 12 properties remaining of the 30 he once owned in Hegewisch and across the region, but now his renters had a hard time paying him. “I needed a break when the going got tough,” likely referring to his financial difficulties following the decline of his career and his bout with influenza during the 1918 pandemic, “and I have a feeling for others,” he said of his tenants. “They can pay me when times are better.” (Hammond Times, Feb. 4, 1938) According to sociologists from the University of Chicago, between 12 and 20% over residents in Hegewisch and all of Southeast Chicago were on relief as early as 1933, a few years before the closure of Pressed Steel.