Since 1979

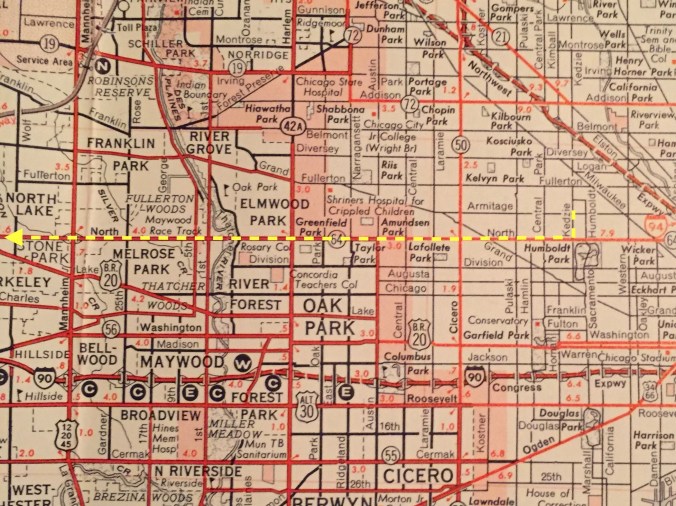

On a cold Saturday evening in mid November, Ernie encouraged me to dig a little deeper to find Chicagoland’s pizza treasures. And with good reason: of the hundreds of choices scattered across the region, there are all kinds of gems easily overlooked, some in relative plain sight. So he pointed us not to a far off and almost hidden place (to us) like Hegewisch, but instead to a destination much closer: the suburban community of Northlake, Illinois.

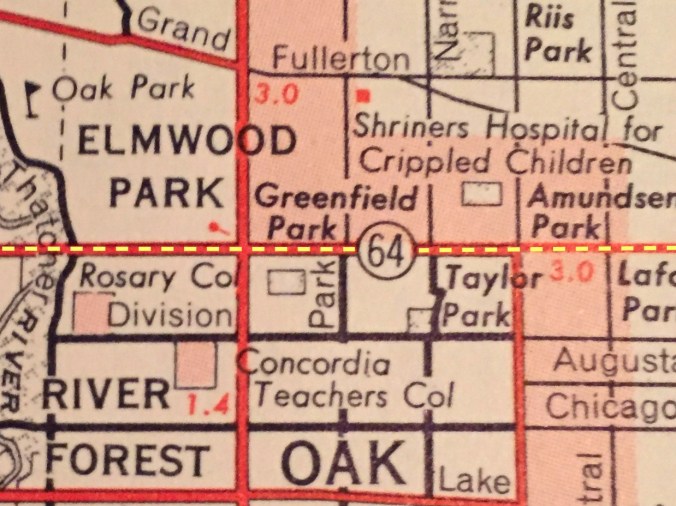

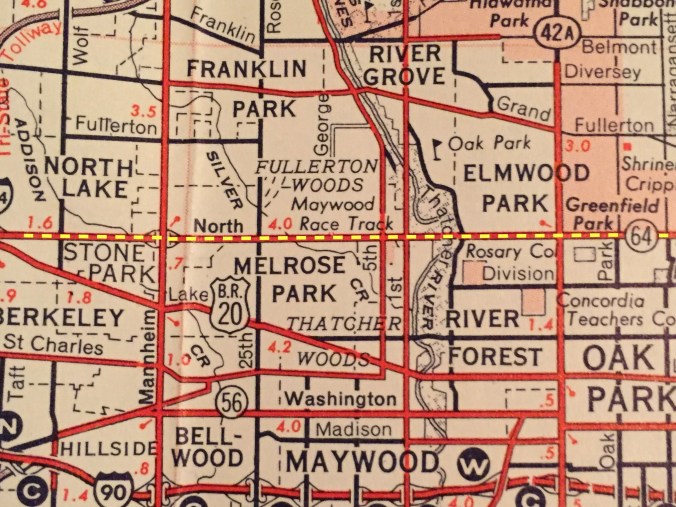

This was a relatively short and easy trip for us, with very few of the twists and turns we’re used to, because Northlake is essentially located just ten or so miles directly west of our Logan Square apartment.

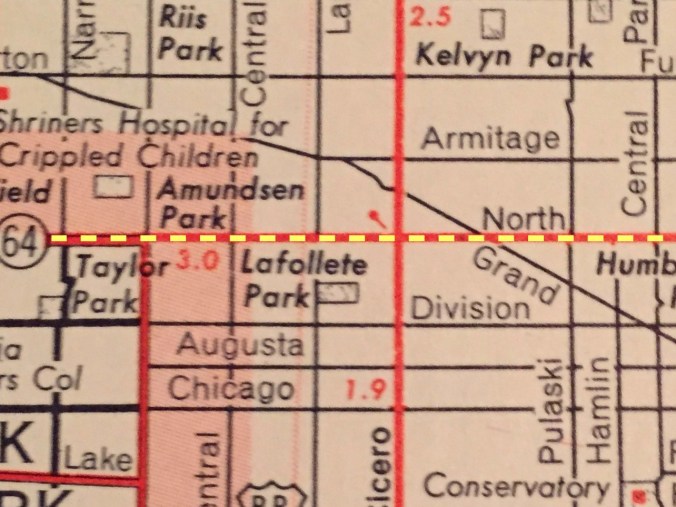

To get there, all we had to do was hop on North Avenue, drive through Chicago’s West Side neighborhoods, then just a few miles past the city limits through a few medium-sized western suburbs.

We had been to a couple of places in the West Suburbs, such as Jake’s in Franklin Park and County Line in Elmhurst. Still, much of the area remained unknown to us. So we settled in the car for the trip, looking forward to learning as much as we could about western Chicagoland and Northlake. The light snow did not deter us, either; in fact it helped me announce to the world that royalty was riding with me.

The fact that our destination was relatively close should not diminish the complexities of world through which we were about to travel; a world with not only a fascinating social and cultural history but also one that possessed a remarkable pizza scene that has almost completely disappeared. You can certainly find pizza on the West Side today, just as you can just about any place in America, but it is more likely to be Little Caesar’s Hot ‘N’ Ready $5 pepperoni rather than a long-running Mom & Pop shop. That said, traveling past many different businesses proudly serving today’s Latino and African American communities, one might not realize that the West Side has a very stellar pizza past. Our first of very few turns was off of Kedzie onto North Avenue in the Humboldt Park neighborhood.

There we passed one of the city’s oldest businesses and one of our favorites in all of Chicago, Roeser’s Bakery.

Holding the title of Chicago’s oldest family-owned bakery (with Pompeii leading the overall oldest category), the still-excellent Roeser’s served as a connecting point between our trip and North Avenue’s lost economy. And we found out there’s even more reason to like Roeser’s. Any basset hounds?

When we read this ad, we thought, “Roeser’s used to make pizza?” But then we remembered where we were: this was Father & Son country.

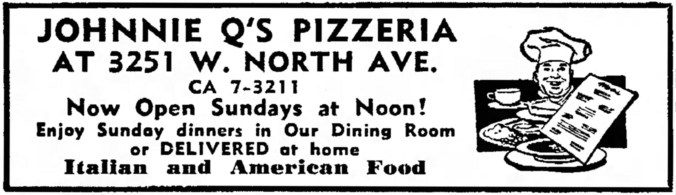

But it was not always just Father & Son or even Mama Luna territory. Located at 3251 West North Avenue between Sawyer and Spaulding (!) Avenues, Johnnie Q’s Pizzeria served Humboldt Park in the 1950s and ’60s, just about a block west of Roeser’s. Occasionally, the name would pop up as “Johnny Q’s,” such as this example from a listing of local businesses participating in a local promotional event.

Source: The Garfieldian, December 19, 1962.

Business must have been good for original owner John Quentere, too. Fourteen cars, Johnny?

Source: Chicago Tribune, August 27, 1956.

But it appears that, according to paid advertisements, “Johnnie Q’s” was the perferred spelling. As the West Side neighborhoods became increasingly car-centric (the Humboldt Park L line was abandoned and torn down in the 1950s), pizza delivery became an easier and more popular option. Johnnie Q’s obliged.

Source: Austin News, March 17, 1965.

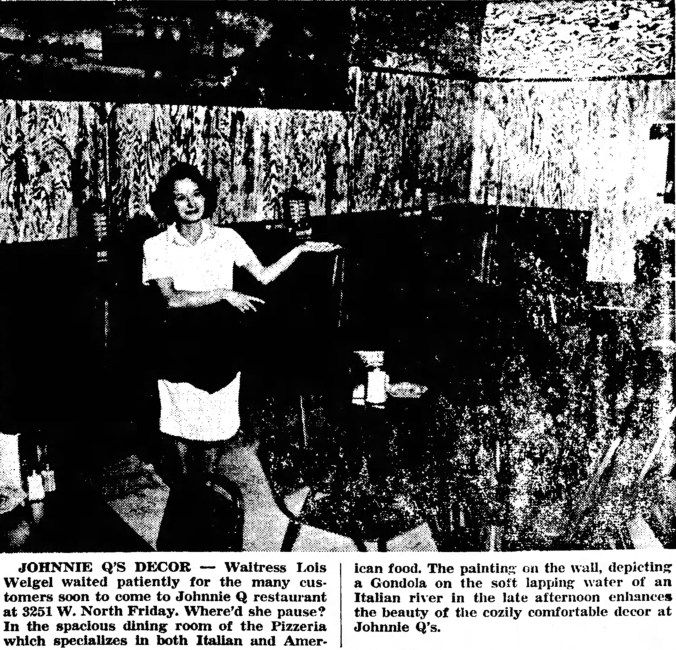

Quentere sold pizzeria was sold to the Martinez family in 1959, who continued to operate it as both a delivery and dine-in spot.

Source: Austin News, April 21, 1965.

A lot has changed. Is this the old Johnnie Q’s dining room?

Source: Zomato.

Today, the storefront is home to La Perla Tapatia, a Mexican restaurant.

About five and a half blocks west of the old Johnnie Q’s, Blackie’s No. 2 was located at 3800 West North Avenue at Hamlin Avenue in the early 1960s. Through the rounded corner entrance the beautiful three-story brick building, square pizzas were a specialty and “all pizzas on a cheese base.” Sausage, of course, was listed as the first topping and it was even cheaper than the mushroom pizza and the green pepper pizza. Also of note the high billing given to to anchovies and shrimp. No pepperoni, as we have yet to investigate if it was even a common topping at the time. The Blackie’s Special was the classic Chicago special with the addition of anchovies! And as a nod to the working-class culture of some West Side areas, the Blackie’s ad noted “Yes, We Deliver To Factories Also.”

Source: The Garfieldian, August 8, 1962.

A Blackie’s Pizzeria–likely Blackie’s No. 1–was located on Ogden in the West Side neighborhood of Tri-Taylor and run by Anthony Basilo.

Source: The Garfieldian, January 6, 1965.

Today, the space is home to Latin Grocery & Liquor, which claims “Donde Se Vende La Cerveza Mas Fria De Chicago.”

As we continued to travel west, we considered the current and historical economic landscape on streets just off of North Avenue, as well.

For instance, Steve’s Pizza, operated by Steve Stramaglia, was located in a one-story brick building just a few blocks south of North Avenue 1255 N. Pulaski Road, not far from the iconic Jimmy’s Red Hots. A contemporary eatery located on Grand Aveune and Pulaski, Jimmy’s opened in 1954 and exists to this day.

Steve’s later became Humble-Pie Pizzeria and included a complete Mexican menu, a mix that is not uncommon in certain neighborhoods in the city today.

Source: News Journal, June 12, 1975.

Today, the space is occupied by El Sitio Caribbean Cuisine, a Dominican restaurant.

Source: Google Street View.

Back on North Avenue we learned that one could find Vito’s Pizza a couple of blocks west of Pulaski, at Karlov, in the mid 1970s. Comedian Horatio Sands apparently grew up in this area and would have been about five years old at the time.

Source: News Journal, December 18, 1974.

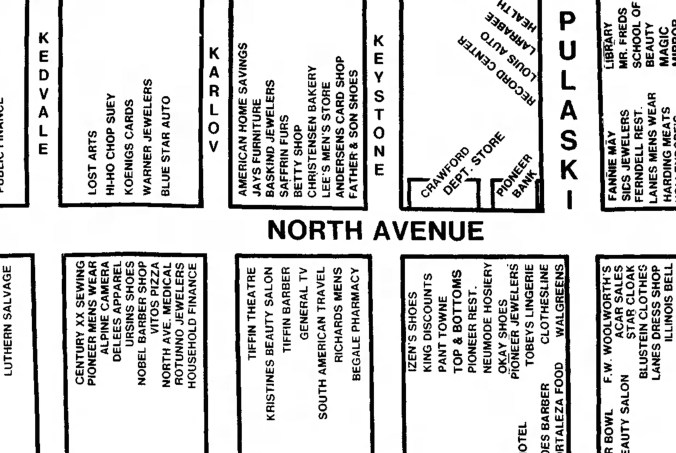

The North-Pulaski business district has long been a very active commercial area. Today, most businesses aim to serve the large Hispanic population now living in the area, with restaurants (independent and fast food chains), clothing stores, and banks. However, a few decades ago there was an even greater of variety of goods and services available to the community, including theatres, bowling alleys, and record stores.

In what we believe could be–though we not completely sure–the Vito’s Pizza location, another business called Guy’s Pizza took over the space occupied by Que Padre! and briefly occupied the storefront at 4107 West North Avenue around 2010 or so. Opened in 1967 on Armitage Avenue, Guy’s Pizza was later located at 3948 West North Avenue and was the unfortunate home base of two drivers that were shot and killed on a deliveries, one in 1987 and one in 2002. That building was demolished sometime in the last decade. This, the last location of Guy’s, was gone just a few years later. Followed by a succession of restaurants, including La Isla Pequena Puerto Rican restaurant, briefly Cemitas y Taqueria Puebla, and, most recently, Braseritos Restaurant, the storefront at 4107 West North Avenue demonstrates the remarkable dynamic evolution of the urban landscape over just a few years.

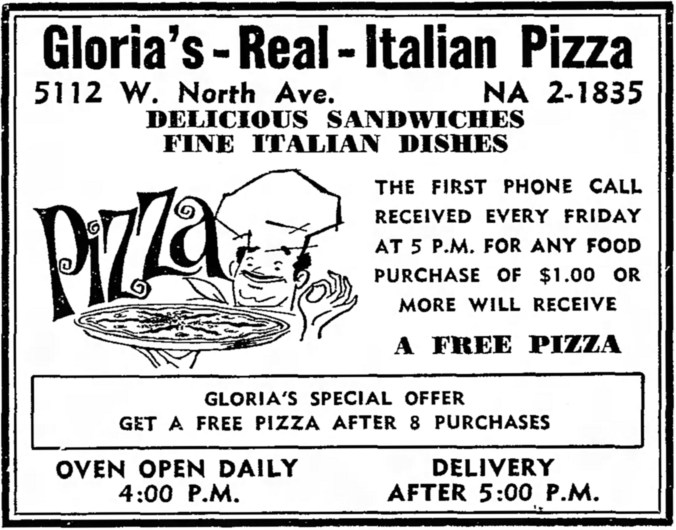

Continuing west past Cicero Avenue, we passed the former location of Gloria’s Real Italian Pizza, which occupied the space at 5112 West North Avenue near Leclaire Avenue in the 1960s.

Source: The Garfieldian, May 27, 1964.

In addition to a fun radio giveaway-style “first phone call gets a free pizza” gimmick, Gloria’s subscribed to the coupon gig, offering a free pizza after eight purchases, an incredible deal considering that some places today offer five dollars off after about twenty coupons. The North Austin pizzeria also offered 25 cent off coupons in the local paper.

Catering, too, by Chef Virgilio! Meat and fowl was available, but there everyday business must have tied up their pizza ovens

Source: The Garfieldian, October 31, 1962.

Most recently, a salon known as Daba African Hair Braiding occupied the storefront of the one-story brick building today. That business has since moved next door while the old Gloria’s storefront awaits a new tenant.

Source: Google Street View.

Meanwhile, a food and liquor two doors west, Lil Vegas, has proprietary signage–and an Old Style sign–that may date to the Gloria’s era, or at least just a few years later.

Source: Google Street View.

Pizza Master had two locations in the North Austin neighborhood. Pizza Master No. 1, was located in one of the storefronts a large three-story yellow brick building at the corner of North Avenue and Latrobe.

Source: Chicago Tribune, July 24, 1977.

The business was sold at auction in 1977, and So Much Style barber and beauty shop occupies the pizzeria’s old space at 5233 West North Avenue today.

Source: Google Street View.

Practically across the street in a smaller, two-story brown brick building at 5252 West North Avenue, Pizza Master No. 2 stayed opened until 1 a.m. and offered free delivery, suggesting that it may have been the smaller carryout and delivery wing of Pizza Master No. 1.

Source: The Garfieldian, October 16, 1963.

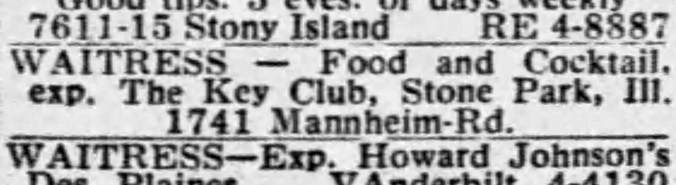

But Pizza Master No. 2 also had a dining room of some sort, as want ads for waitresses were published.

Source: The Garfieldian, May 26, 1965.

Today, the space is occupied by Pickett’s Barber and Beauty Salon.

Source: Google Street View.

One independent pizza shop still open on North Avenue. Victor’s Pizza, which has served North Austin since 1974 at 5418 West North Avenue, in the L cross streets.

Source: Victor’s Pizza.

A Fauld’s oven is visible on business’s nicely-maintained Facebook page, as are photos and simply statements about serving the community. Victor’s definitely sounds like a good choice for the Pizza Hound to visit in the future. We hope we get to. In the meantime, you should check it out and keep the West Side pizza tradition alive.

North Austin had even more options that pre-dated Victor’s, including Tower Pizza, a pizzeria located about a block and a half east of Central Avenue in the 1960s. Leaning Tower of. . .Pizza? Umberto Borini purchased the pizzeria in 1959. After remodeling and expanding the business, he added an “Italian menu” with popular chicken and veal dishes, as well as an “American menu” with steaks and chops. The Garfiedian, a local promotional newspaper, noted “A new innovation will be the introduction of five different pizza sizes, an accommodation for patrons making us of the free delivery service.” (April 1, 1959)

Source: The Garfieldian, April 1, 1959.

It is possible business changed hands once again, as just a few years later the business was advertised as Alberti Tower Pizza. Offering free delivery in a 20 block area, the business claimed to “Specialize in Pizza. . .,” perhaps backing away from the wider menu Borini had developed a few years earlier. Now, only three sizes were listed instead of the previous five. Sausage, of course, was listed near the beginning of the topping list, following cheese only. Shrimp and anchovies were there, as was pepperoni, a topping apparently present though much less ubiquitous in Chicago than as it is today.

Source: Austin News, May 22, 1963.

Rather than a tower, the building looks more like a castle wall (but then again today’s Pizza Castle is located in a one-story strip mall). Nevertheless, the storefront at 5517 West North Avenue recently appeared to be occupied by a church.

Source: Google Street View.

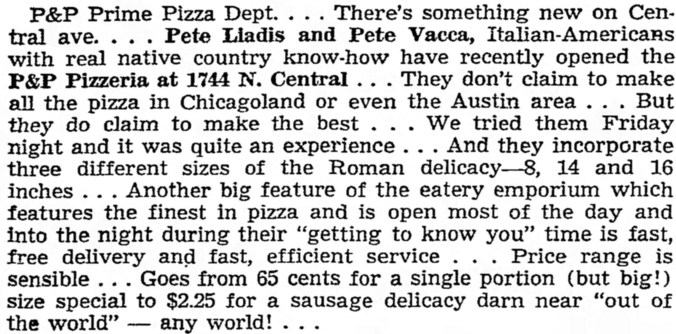

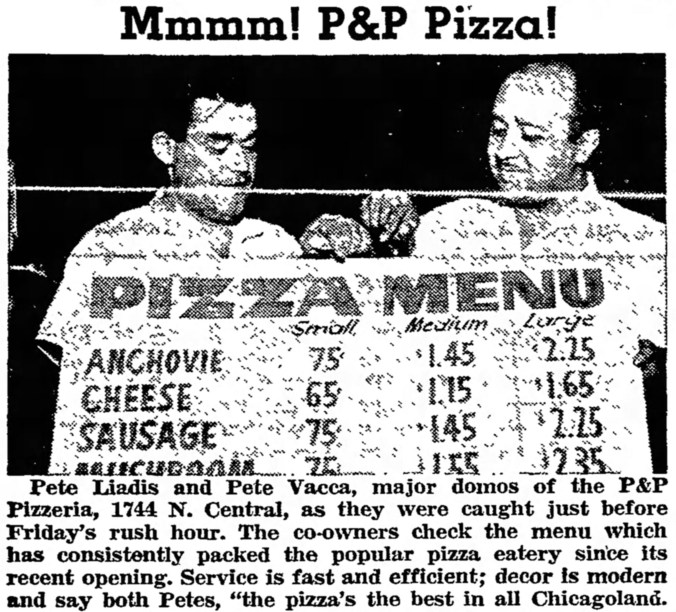

We also learned that in the 1960s P&P Pizzeria could be found just a little off our current path, a few blocks north of, well, North Avenue.

Source: The Garfieldian, October 10, 1962.

Pete Liadis and Pete Vacca opened the business in the early 1960s. Many of their advertisements used the popular Rodgers & Hammerstein song “Getting to Know You” from the musical The King & I to emphasize their quality and customer service focused efforts to break into the lucrative local pizza market.

Source: The Garfieldian, September 19, 1962.

Pete Liadis ran into some trouble at his old business, the Walnut Tap at 3958 West Ferdinand in the West Humboldt Park area in the early 1960s. His business was bombed several times resulting in thousands of dollards in damage. This story is quite strange. Did Liadis have business or personal enemies in the neighborhood? Did he support–or oppose–labor unions and get caught in the middle of a contract fight? The tavern bordered an industrial area, after all, and was likely patronized by local workers. Racial tensions in the neighborhood? A lone, serial bomber years before that sort of thing was even recognized? What about troubles with the mob? Did Liadis owe money to some dangerous people? Did he not pay off crooked cops for protection? Unfortunately, we never discovered any conclusion to this story, and as far as we know, the culprits were never caught. But we have to wonder if Liadis and the folks inside the Walnut Tap knew exactly who was causing the trouble. Today, a state-owned parking lot occupies the address.

Source: Chicago Tribune, April 6, 1962.

Pizza may have given Liadis a fresh start, because just a few later in 1962 he appeared in the local paper with Vacca happily holding a large P&P Pizzeria wall menu. Note the top billing for anchovies on the menu! Times sure have changed.

Source: The Garfieldian, October 10, 1962.

P&P closed long ago, and its former home at 1744 North Central Avenue–a one-story building fronted by a handful of parking spaces–appears to be a bar called Carolyn’s Lounge, which has been painted a striking shade of pink and possibly stuccoed.

Source: Google Street View.

Back on our regular route for the evening, we learned that Ann’s Pizza was located at 5743 West North Avenue at Menard Avenue, directly between Central Avenue and Austin Boulevard, in a large three-storefront, two-story brown brick building adorned with masonry.

Source: The Garfieldian, December 19, 1962.

Owner Ann Aloia probably wasn’t too happy when Johnny Quentere, who had sold off his first pizzeria in Humboldt Park in 1959, returned to the West Side to open Q’s Restaurant. The new Q’s, was located in the storefront of a three-story brown brick building on North Avenue, after all, basically across the street from her business.

Source: The Garfieldian, November 11, 1964.

Both Ann’s and the new restaurant, often marketed as The Original Q’s, though, likely found enough business to share in the heavily populated–and still growing–Austin section of the West Side. There certainly was money to be made, and Quentere invested in advertising and dining room improvements accordingly, while Aloia appeared to not focus on promoting her business quite as much.

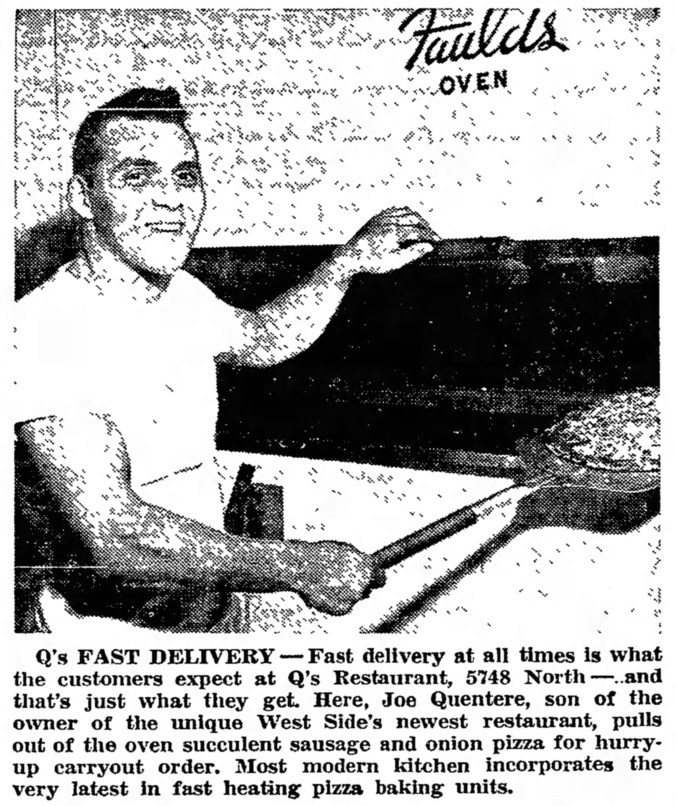

Q’s was a family operation, from the kitchen to the dining room.

Source: Austin News, September 10, 1964.

The restaurant served thin crust tavern-style pizza–with sausage, of course–baked in a Fauld’s oven. In many Chicago neighborhood pizzerias, on this front, little has changed. Victor’s Pizza uses one just like it.

Source: The Garfieldian, August 26, 1964.

Q’s also had a number of loyal local customers. Some came for cheesecake and coffee.

Source: The Garfieldian, November 11, 1964.

Others came for the pasta. There’s no pizza visible here, but one can see spaghetti, a table jukebox, and a pack of smokes. Joseph Rago, one of the diners, was no doubt familiar with two different businesses with shared roots and similar names.

Source: The Garfieldian, October 27, 1965.

Through the grainy black and white of a digitized 1960s newspaper, we can only imagine how delicious John Quentere’s pizza was.

Source: The Garfieldian, December 30, 1964.

Quentere continued to advertise his establishment widely despite the fact that his old buisness, Johnnie’s Q’s, was still open in Humboldt Park, run by the Martinez family.

Source: Austin News, March 17, 1965.

Q’s closed its doors on North Avenue in late 1980s and the storefront has been consistently vacant in the last ten years.

Source: Google Street View.

The mid-century rise in automobile ownership, the spreading out of Chicago’s population into all corners of the city and suburbs, and the overall increase in disposable income helped lead to the pizza delivery. Many West Side pizzerias, including Q’s, advertised fast–and often free–delivery to one’s doorstep. A sign very similar to the one pictured–and likely the exact sign–stands outside the landmark business in Hillside, the third incarnation of Q’s, opened by Theresa Quentere and her son, Al Quentere. We look forward to trying it someday.

Like the second incarnation of Q’s, Ann’s did not last, either. By 1968, the “centrally located, long established” pizzeria was for sale. The classified notes “owner deceased,” so unless the business had previously changed hands, Ann Aloia had passed away. The seller, it seems, wanted to unload the business quickly stating “will sacrifice” and “make an offer.”

Source: Chicago Tribune, January 25, 1968.

The old space has been home to beauty salons for many years and is currently one known as Walk By Faith.

Source: Google Street View.

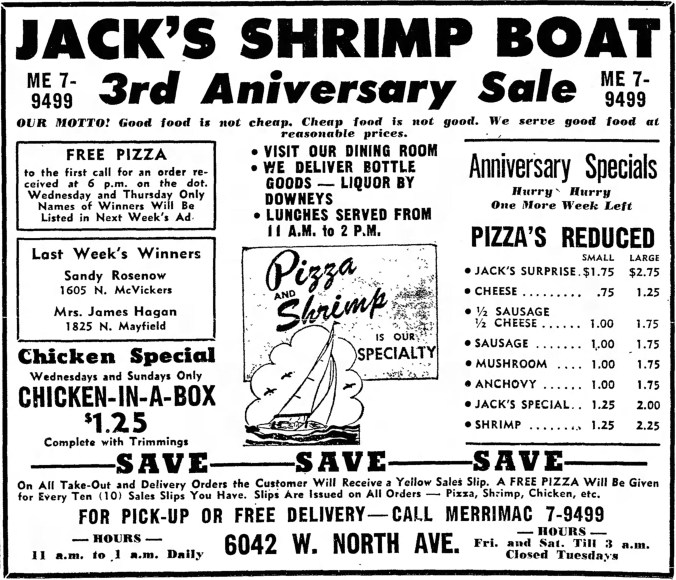

In the Galewood neighborhood, one of the westernmost neighborhoods of the city, North Avenue serves as the borderline between Chicago and the suburb of Oak Park. There we learned of one of the more interesting West Side pizza legacies. The story starts with Jack’s Shrimp Boat and Restaurant. Apparently taking its name from the popular song performed by Jo Stafford Jack’s Shrimp Boat opened in 1955 serving not only shrimp but pizza, as wel. In fact, the increasingly popular pizza appeared to have just as much or more focus than the restaurant’s original namesake food.

Source: The Garfieldian, October 15, 1958.

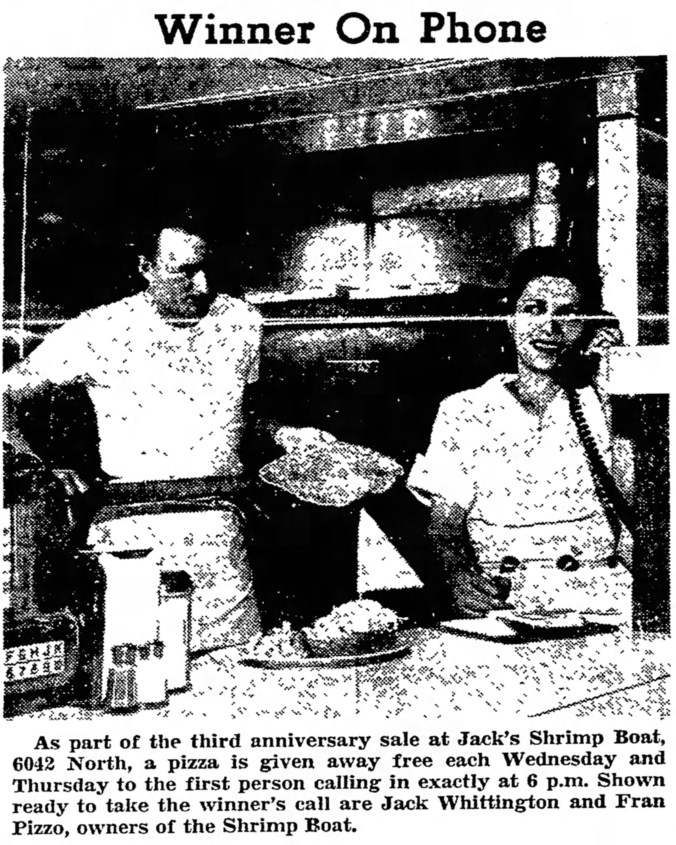

Keeping remarkably late hours (closing at 1 a.m. during the week, and Fridays and Saturdays until 3 a.m.) Jack Whittington and Fran Pizzo ran for at least three years serving thin pizzas. Diners could enjoy music from table jukeboxes. Customers received a free pizza after collecting ten of the yellow slips that came with each delivery order.

Source: The Garfieldian, October 8, 1958.

Shirley Eastman, a waitress at the Shrimp Boat, got some attention in gossip column of the local Garfieldian newspaper in the fall of 1958. Hmm. . .”voted most likeable waitress in town. . .”? There was a vote? Was there a happy discussion around a Shrimp Boat table? Did the writer or someone else have a romantic interest in Ms. Eastman? We’re not sure. Nonetheless, Eastman’s excellent service got her mentioned in the same column as the legendary Empire Room at the Palmer House.

Source: The Garfieldian, October 15, 1958.

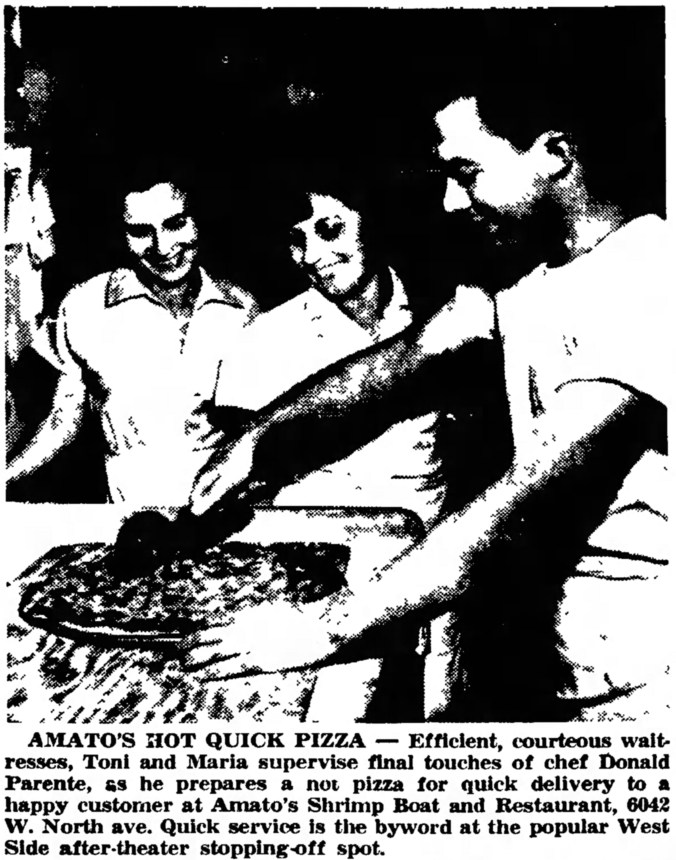

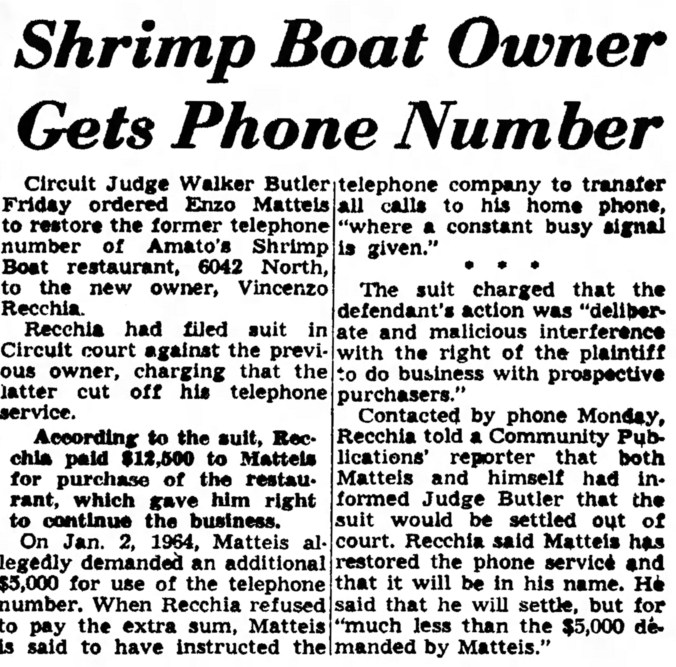

Enzo Matteis took over the Shrimp Boat restaurant in 1962, now under the name Amato’s Shrimp Boat Pizza and Restaurant. Did Matteis buy it from someone named Amato?

Source: The Garfieldian, November 6, 1963.

For some reason, we can’t find clear evidence that anyone named Amato ever owned the business, but it is a logical connection. The earliest appearance of the Amato’s name that we could find was a classified from December of 1962.

Source: Chicago Tribune, December 8, 1962.

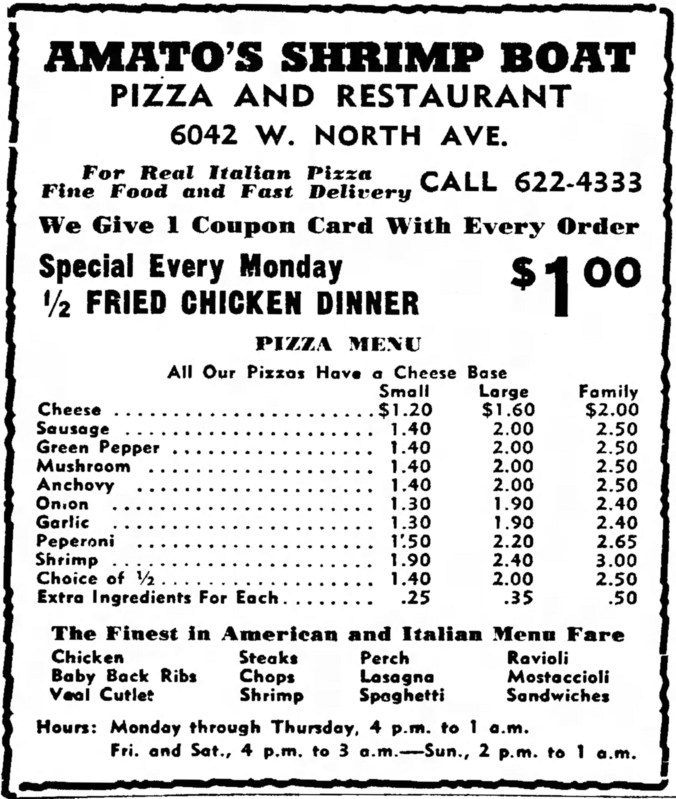

Matteis added steak, chops, veal, and ribs to the menu, as well as various pasta dishes such as spaghetti, mostaccioli, and lasagna.

Source: Austin News, November 6, 1963.

Reporting and promoting that “Amato’s Shrimp Boat Finally Landed. . .,” the Austin News stated “. . .the true Italian style of living can be found at one West-Northwest Side pizzeria and restaurant–even if it is way out in Austin.” (October 16, 1963)

Source: The Garfieldian, December 4, 1963.

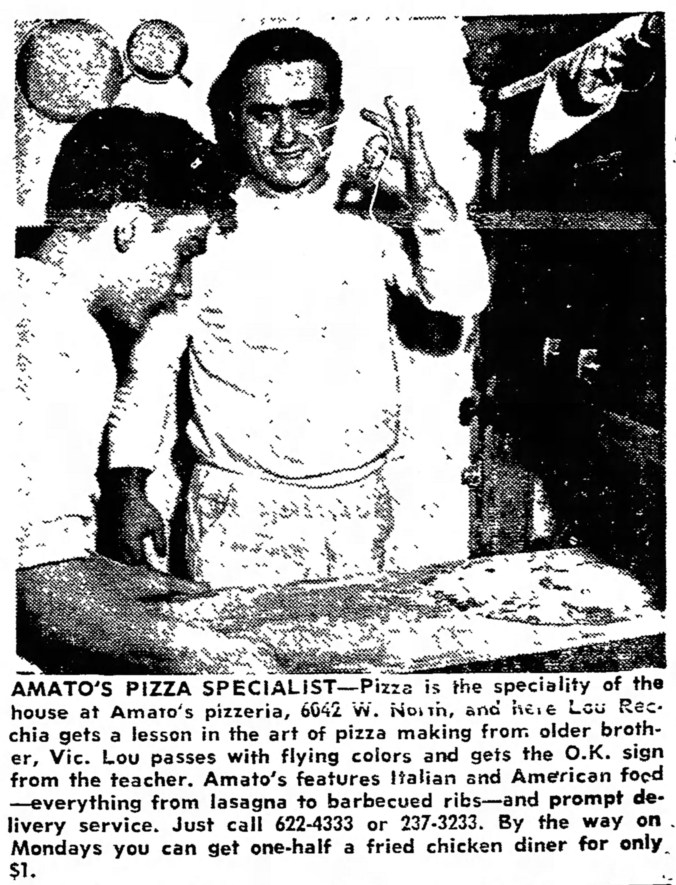

Victor Recchia and his father, Vince, bought the growing Shrimp Boat from Matteis. Immigrants who came to the United States in 1958 from Bari, Italy, Victor stated, in a 1984 Tribune profile, that “We thought America was a place to go live a better life [. . .] That’s what we always believed.” Victor started gaining pizza experience early, working first as a busboy at a pizzeria on Exchange Avenue at the age of 13. A couple of years later, he took a job as a pizza maker at Tony’s Pizza (later Tony’s Steak House) on Fullerton, where he agreed work for free until he mastered the job. Soon he was managing, and within a year he a had saved up enough money to buy Amato’s sometime in either later 1963 or early 1964 (though one article two decades later says 1962 and later. . .memory and reporting are funny things). Despite Matteis’s earlier menu expansion– even “Green Noodles”–and Recchia running a chicken special, the business increasingly focused on the main draw: pizza. Thin crust, not deep dish, was the star, just like in most Chicago neighborhood pizzerias to this day.

Source: Austin News, October 23, 1963.

Still, just as many neighborhood pizzerias do today, Amato’s also served fried chicken.

With other members of the family involved, including brothers Vito and Frank and their father, Vince, Amato’s grew even more successful, apparently with a strong delivery business.

Source: The Garfieldian, February 9, 1966.

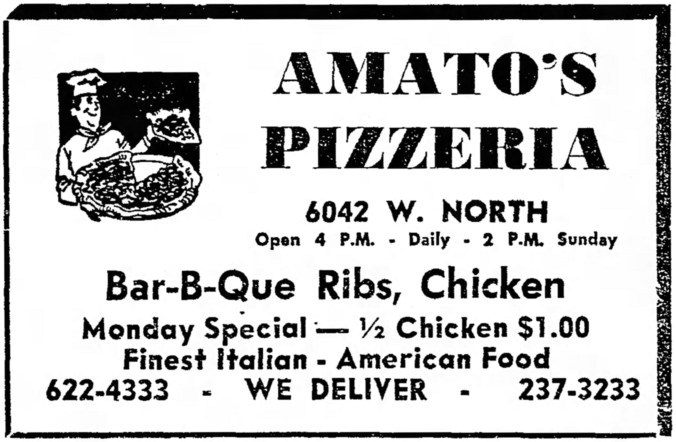

The Recchias, even with fried chicken on the menu, focused on their main draw and renamed the business Amato’s Pizzeria, at least in advertisements, by 1966. Hey, isn’t the that the Pizza Master guy?

Source: The Garfieldian, January 26, 1966.

Still, despite being referred to as “Amato’s Pizzeria,” the Shrimp Boat name persisted into the late ’60s.

Source: The Garfieldian, February 25, 1968.

Victor sold the business and in 1971 he and his brother, Lou, purchased the defunct Calo Pizzeria at 5402 North Clark Street in the Far North Side Andersonville neighborhood, right next to the Calo Theatre and later the Calo Bowl. The Recchias moved Calo just a few steps away to the current location at 5343 North Clark in 1979. Today’s Calo sign notes “Since 1963,” a curious date.

Source: Google Street View.

It is possible that it was the year that the previous owners actually opened Calo Pizzeria, as we can find no evidence of the business existing prior to around 1964 or 1965, and then all we found were classifieds. It is possible, though, that the date traces back not to the beginning of the Clark Street Calo restaurant, but the Recchias first business, Amato’s Shrimp Boat Pizzeria on North Avenue. Either way, it appears that Victor Recchia has taken to stating that he opened Calo in 1963. It’s probably just easier than explaining the whole Shrimp Boat and Calo Pizzeria stories.

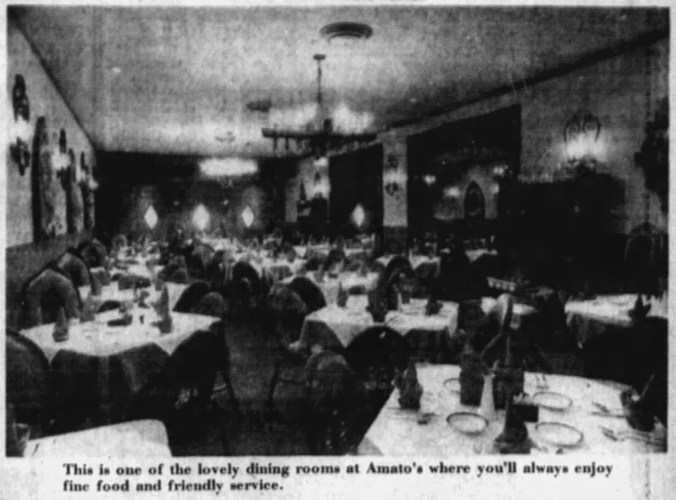

The old Shrimp Boat business evolved into more of fine dining experience when Domenic Parato, a former Shrimp Boat dishwasher, took to over bought it some time in the late ’60s or early ’70s. Vic Recchia claimed to have sold it for five times what he and his father had paid just a few years before. Parato had dreams for the business and was determined to make his large investment worth it. He expanded in the establishment into adjoining buildings giving the restaurant three separate dining rooms and enough space for banquets.

Source: Chicago Tribune, September 16, 1982.

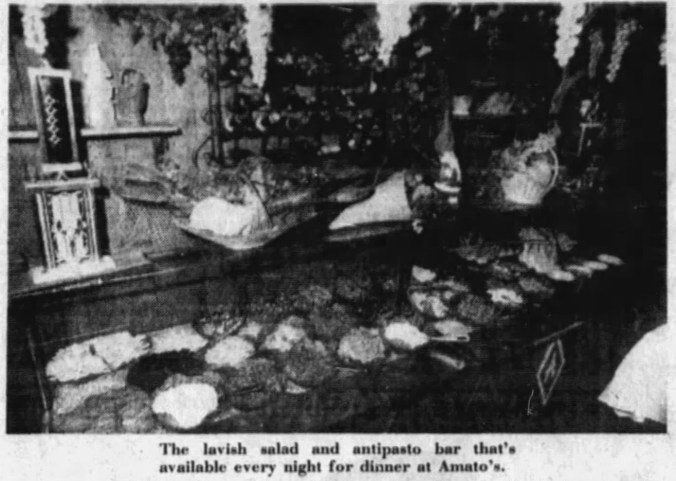

A “lavish salad and antipasto bar” was a part of the dining experience at Amato’s

Source: Chicago Tribune, September 16, 1982.

Advertisements changed from the folksy, working-class utility of the Shrimp Boat and Amato’s Pizzeria to ones emphasizing elegance, romance, and, most of all, “Outstanding Italian Cuisine.”

Source: Austin News, June 8, 1977.

Thin crust and deep dish pizzas were still noted, and carryout and delivery was still available, but photographs of the proud Parato, dubbed “Your host Domenic,” decked out in a nice suit and tie emphasized the more intimate atmosphere the restaurant now hoped to convey.

Source: Chicago Tribune, November 10, 1979.

Amato’s run as a fine Italian restaurant lasted at least into the 1980s, but the vast change witnessed across the West Side following deindustrialization, suburbanization, and the 1968 riots also came to the business. In a either a remarkably apt coincidence or bizarre irony, the building that once housed the original Shrimp Boat/Amato’s Pizzeria was demolished (as were the adjoining buildings), while today, a Kentucky Fried Chicken/Long John Silver’s fast food restaurant–parking lot and drive-thru included–occupies the spot. More than anything, the change can be viewed a the evolution of the local North Austin economy and as well as the larger American economy in the last five or six decades.

Source: Google Street View.

As for what happened to Amato’s, we originally were not sure if it closed for good or just moved somewhere else, and we’re not sure when any of that happened. There’s an Amato’s Pizza on North Harlem about two blocks north of North Avenue that claims to have been in business since 1966.

Source: Amato’s Pizza.

Despite this date, we wondered if the two businesses somehow connected. The first instance of we’ve seen our particular business of interest advertised as Amato’s Pizzeria and not Amato’s Shrimp Boat was late 1965, so the timeline doesn’t match up based on our evidence. A new owner in 1966, then a move to North Harlem Avenue sometime later, perhaps? We know the Recchias owned Amato’s until at least 1966 based on photographs in the local paper.

Source: The Garfieldian, January 19, 1966.

But a later Tribune profile states that they sold Amato’s in 1971, so again the dates don’t match conveniently. The Fauld’s oven at today’s Amato’s definitely connects it to at least the 1960s.

Then we found the key: the phone number used at Amato’s Pizza on Harlem is the same phone number used at Amato’s Pizzeria in the 1960s. And that phone number was considered central to the success of the business, according to a 1965 lawsuit. After selling the Shrimp Boat to the Recchia family, Matteis, essentially held the phone number for a $5,000 ransom over the original $12,500 purchase price of the business. Evidence suggests that the number in question is 622-4333, which replaced the original number with a lettered prefix, MErrimac 7-9499, in advertisements as early as 1963. And perhaps this incident was the genesis of the second phone number, 237-3233, sometime thereafter. Both seven digit phone numbers, now with the 773 area code, are still in use to this day.

Source: Austin News, January 13, 1965.

Today, the business, owned by brothers Santo and Mario Gariti, seems to have refocused as a branded small local chain of carryout, delivery, and casual dining, with a location in Aurora that also serves Naperville, and another in Lincoln Park right at Clybourn and Sheffield. This fits with the historical migration of the Shrimp Boat’s clientele and their descendants: move slightly farther west to the near suburbs, then maybe their children move even farther west to Naperville, then their grandchildren move to trendy Lincoln Park and stay after attending DePaul University. Through the changes, chances are the tavern-cut thin crust pizza at today’s Amato’s is very close to what you could get at Jack’s Shrimp Boat, Amato’s Shrimp Boat, and the first Amato’s Pizzeria. We hope so.

Continuing west just about a block west of Shrimp Boat, Capizzi Cocktail Lounge Restaurant served pizza, likely in a dimly lit setting with live entertainment, in the 1970s.

Source: News Journal, March 22, 1970.

Recently, the building housed a day care and preschool, but today is home to Textile Restoration. Present day pizza options start to pick up, as well.

Source: Google Street View.

Still in Galewood, we learned one could enjoy a carryout pizza at Grand Slam Pizza from the mid 1960s until just the last few years. Grand Slam, located in one-story mid-century modern storefront with large front windows at 6856 West North Avenue, was known for its butter crust pan pizza. They offered a six pack of Coca-Coca with any family size pizza. Perhaps RC Cola had yet to make the inroads it would later.

Source: News Journal, June 12, 1974.

Would love to buy this menu, but at $75 we’ll have to pass. Just as today, cheese and sausage is listed near the top of the pizza menu, almost a default choice. Next on the ingredient list? Mushrooms. This seems to hold true today. Grand Slam next listed peppers. “What kind of peppers?” “Come on, you know. Peppers.” After that, “Anchovy” remarkably is ahead of “Peperoni.” The latter was listed at a higher price only matched by shrimp and salami, suggesting it was a newer product less readily available than sausage. The “Vito Super Deluxe Pizza,” named for owner Vito Casola, was the same deluxe found almost everywhere in Chicago.

Fried chicken, shrimp, pasta, Italian beef sandwiches, Italian sausages, and pizzaburgers were available, too.

Casola operated the beloved restaurant until selling it around 2006. The space was thereafter briefly home to Don Chico’s Mexican grill, and has been home to Nick Jr.’s Grill for about the last decade, with the original diner bar and swivel stools intact. You can still get pizza nearby: a location of Edwardo’s Natural Pizza, a chain known for their massive stuffed pizzas, is practically across the street.

Source: Google Street View.

At Harlem, North Avenue crosses the city’s edge and moves into Elmwood Park. From here the architectural landscape changed noticeably from an urban to one significantly more suburban: from tall buildings close the street fronted by sidewalks to interspersed one- and two-story structures mostly built in the mid- to late-twentieth century when the automobile dominated city development. There were pockets of newer structures in between, of course, but overall a gradual change was noticeable.

There are Italian–and pizza–options through here, too, reflecting the historical Italian heritage of the area. Long ago, there was a place called Victory Pizza in the northern portion of town on Grand Avenue.

Source: Chicago Tribune, June 3, 1952.

This site eventually became home to a legendary Chicagoland pizza institution. Friends Michael Caringella and Armand Christopher purchased the Victory Pizzeria in 1956, which contained six booths and, like Jack’ Shrimp Boat, a diner counter with stools. Apparently, they flipped a coin to see who their acquisition would be named after. Caringella won, but chose to name the business after Christopher to push off any complaints to his partner. Thus, the business was named Armand’s Victory Tap. The owners expanded the business grew more and more successful, adding a full bar as well as room for 300 customers, while the name was shortened to simply Armand’s. According to Claire Vartabedian of the Daily Herald, at one point the business needed 40 delivery drivers on the weekends to meet local demand.

Source: Google Street View.

Nothing lasts forever, it seems, and sadly the original location of Armand’s closed for good around 2009. While the recipes live on in several other Armand’s locations in both Chicago and the suburbs, the longtime building in Elmwood Park has since been demolished. With it, a link to Chicagoland’s storied pizza past was destroyed. Today, the site at 7402 West Grand–long home to pizza traditions and memories–is simply a parking lot for a banquet center next door. A least the hall in question, Elmcrest, proudly run by the Biancalana family, is an even older business with roots in serving first ice cream during Prohibition, then, as Biancalana’s Restaurant from the 1940s through the 1990s, beer, Italian dishes, and. . .pizza. Even if pizza is not on the current menu, the Elmcrest holds onto tradition while highlighting the demographic evolution of the near West Suburbs by offering quinceañera packages for the growing local Latin America population.

Source: Google Street View.

Still, pizza abounds in the west surburban area: there’s the aforementioned Amato’s; Vito’s Old Italian, a new incarnation of the old Danny’s on 15th Avenue in Melrose Park; Capri Italian Foods market; Massa Cafe Italiano; and Trattoria Peppino. (Don’t forget to check out Johnnie’s Beef, Russell’s Barbecue, and New Star Restaurant, a Chinese eatery in business since 1954!) And pizzas are still available at Old World Pizza, located at 7230 West North Avenue in a long brick strip mall that fronts North 72nd Court. And the area’s pizza past keeps giving. For instance, in the 1970s Elmwood Park was also home to Nick & Son’s Home Chef Pizza at 7700 West North Avenue. The original building appears to have been demolished and replaced by a multistory condominium building.

Nick & Son’s was just across the street from the current location of one of our favorites, Jim & Pete’s. Serving near-perfect Chicago-style thin crust pizzas since 1941, the west suburban institution was originally located on the Chicago’s West Side at 802 N. Crawford, today’s Pulaski Road, at Chicago Avenue. We actually passed Jim & Pete’s second location at 7315 West North Avenue in River Forest on our westward trip .

Continuing west on North Avenue, also known as Illinois route 64, we left Elmwood Park and passed through the Huppert and Thatcher Woods, briefly on the border for the city of River Grove, and crossed the Des Plaines River, inching closer and closer to our destination. We had been in the suburbs for a few miles when we arrived in Melrose Park.

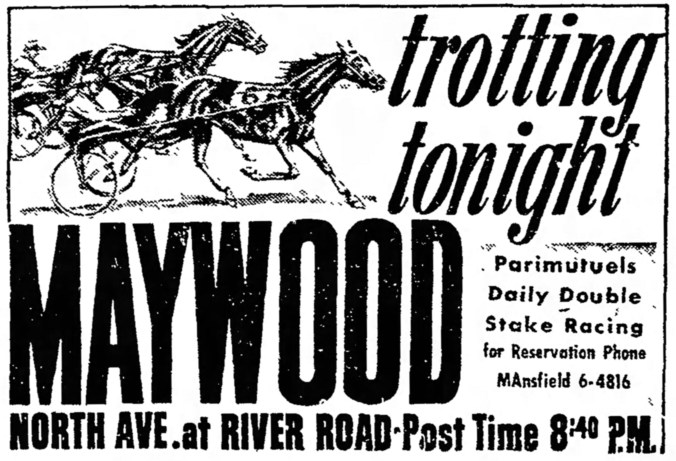

Crossing first 1st Avenue, the massive Maywood Park racetrack loomed on the south side of North Avenue. The park, which closed after nearly seven decades horse racing in 2015, is not actually located in the city of Maywood, as the name suggests, but instead located in (well, officially surrounded by) Melrose Park, while the Maywood community is instead a couple of miles to the south.

Source: The Garfieldian, September 8, 1960.

Melrose Park, a city of 25,000 people with a traditionally strong Italian heritage (not to discount the German, Polish, Irish, and other ancestries of residents, including in recent decades a growing Hispanic community), has a number of pizza options, particularly on Division Street. One of the first pizza places were saw was a suburban-style location of the legendary Home Run Inn. From there, North Avenue served the as the dividing line between the corporate limits of Melrose Park (with the main section of that city actually already in the rear view) and neighboring Stone Park (another town once heavily populated by Italians but now majority Hispanic) increasing from four lanes of traffic to six. All in all we passed a variety of structures: single-story and two-story mid-century commercial buildings, strip malls, a number of big box stores and services, some railroad tracks, and some older industrial complexes. In some ways, it had been a very short trip, but considering how much we had seen and learned, we had come a long way, even from the edge of the city into the West Suburbs.

So our very quick tour of North Avenue suggested to us there was much more to learn about the pizza history of the West Side and the West Suburbs; a history certainly worth revisiting later. Who is this pizza hero?

Source: The Garfieldian, January 19, 1966.

But we had still had a stop down the road, and after just a couple of more minutes driving through the wet snow we had arrived in Northlake.

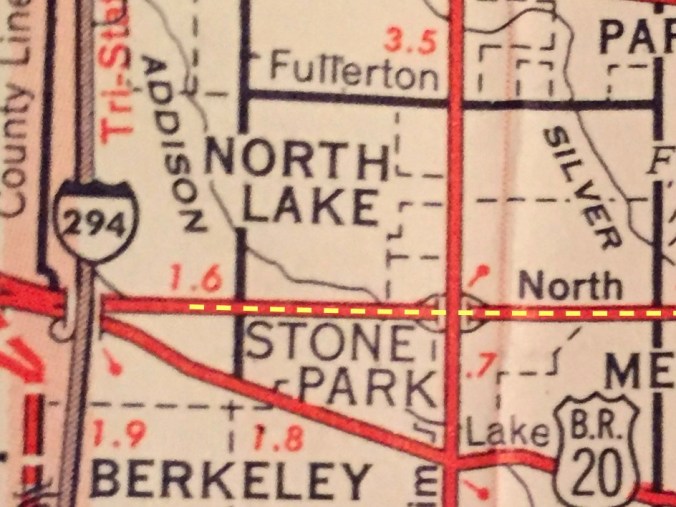

✶ ✶ ✶ ✶

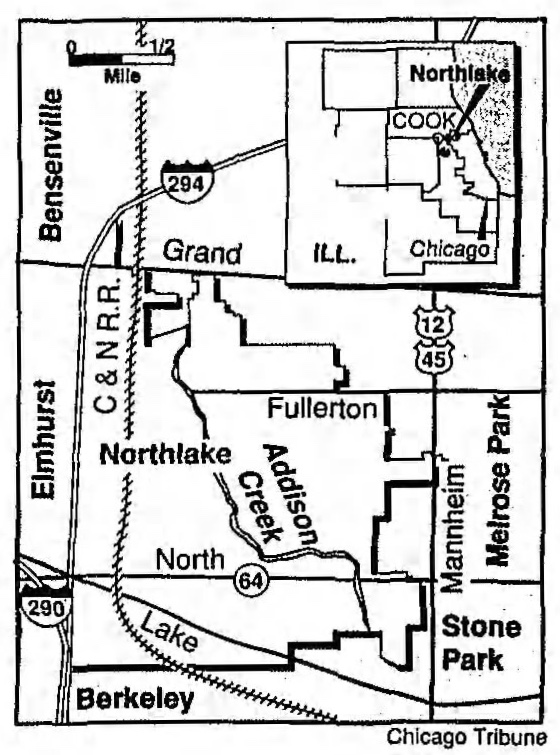

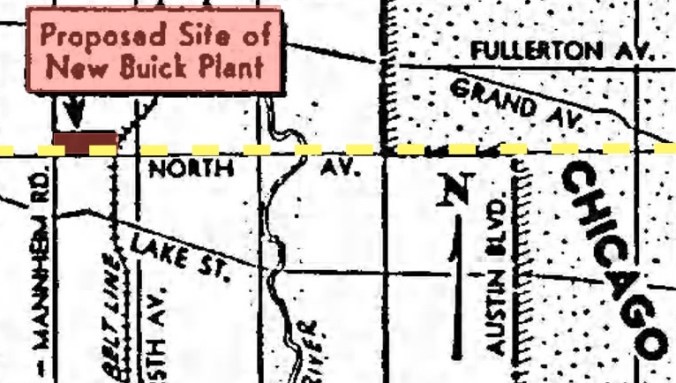

Located also at the westernmost edge of Cook County, Northlake is apparently so named for its two prominent east-west thoroughfares, North Avenue and Lake Street, which (after the latter makes a slight turn to the northwest) intersect at the city’s western border. To the west, the community is bounded by the DuPage County city of Elmhurst and the Tri-State Tollway (Interstate 294), Bensenville to the northwest, Franklin Park to the north, and, to the east of Mannheim Road, the communities we had just traveled through, Stone Park and Melrose Park.

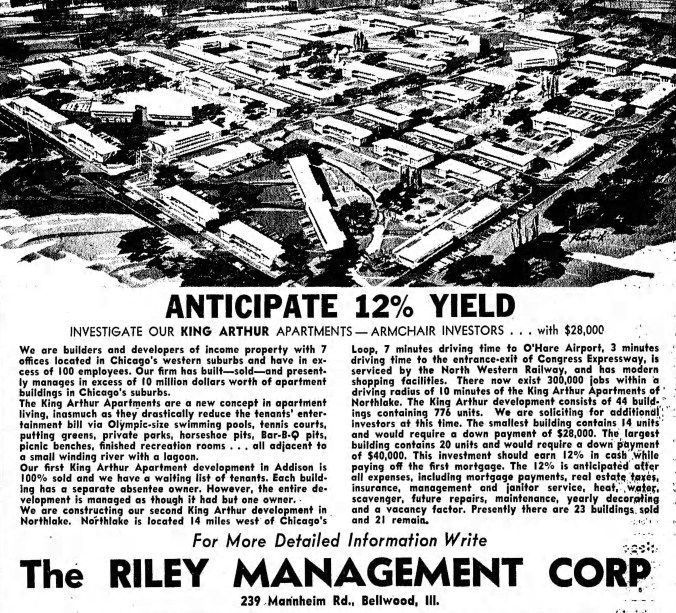

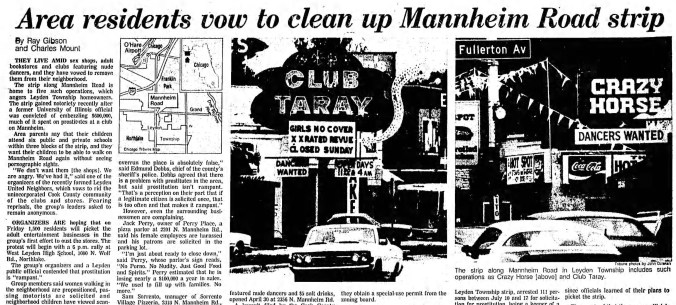

Source: Chicago Tribune, September 14, 1991.

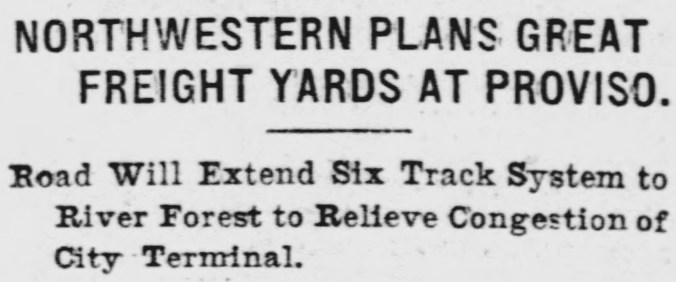

Like many of Chicago’s suburban communities, Northlake grew up rather quickly in the post-World War II era. Prior to the war, the area was comprised mostly of farmland, but railways routed nearby positioned the area with sufficient transportation to support heavy industry. Originally built in 1912 on swampland filled with slag from Chicago’s steel mills (we wonder if this included the great Southeast Side mills) and named for the township in which they were located–the vast Proviso Yards helped spur this development. Dubbed in the press “the finest yards west of Pittsburg (sic)” and expanded in the late 1920s, these classification yards for the Chicago and North Western Railroad were constructed along the west and south of the present-day city, and connected the then-rural area to the massive city of Chicago and the rest of the continent.

Source: Chicago Tribune, November 2, 1912.

It was one of the largest rail yards in the Chicago region and provided numerous jobs.

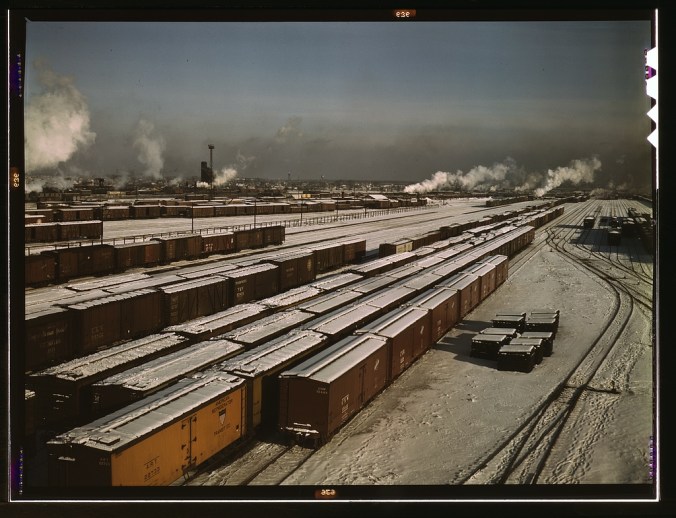

Source: Jack Delano, 1942, Library of Congress..

The Proviso Yards, in use to this day, border several communities including Melrose Park, Stone Park, Bellwood, Elmhurst, Berkeley, and even Franklin Park. And, of course, Northlake.

Source: Chicago Tribune, May 27, 1954.

In spellbinding color, photographer Jack Delano masterfully captured a wide picture of the Proviso Yards for the Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information in 1942 and 1943. The slides, available through the Library of Congress, bring to life a crucial point in the history of Northlake and surrounding communities, as well as a bygone era of American industrialism. Hard work was conducted outside.

And inside, as well, especially within the roundhouse.

As in most of Chicago, the biting cold of winter wind and snow did stop not work at the Proviso Yards.

Nor did regular shifts. Like the city’s steel mills, the yard ran at all hours of the day and night.

Some workers, ranging from clerks to skilled operators to foremen to educated professionals, could to varying degrees avoid most of the yard’s grinding physical labor.

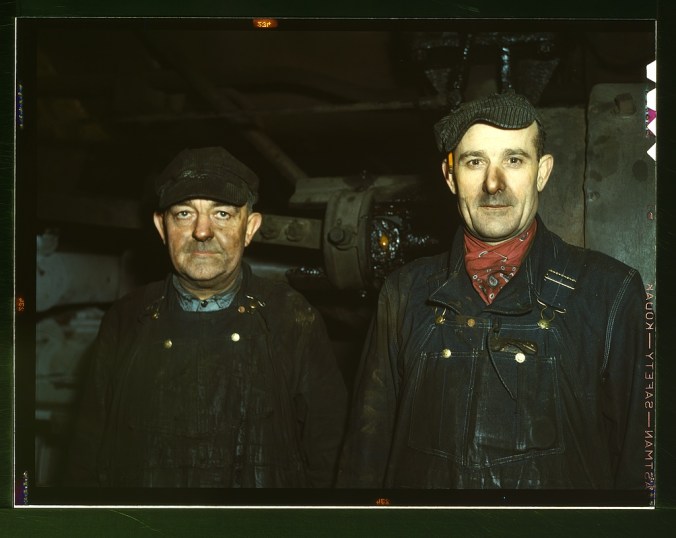

For most at the Proviso Yards, however, each day was filled with hard, dirty, and often dangerous work.

And for many, the job took an obvious toll.

Since these images were photographed seven and a half decades ago, the American economy has changed drastically. Backbreaking work of this type is experienced by fewer and fewer Chicagoans as each year passes. The descendants of these men instead may work in an office, in a restaurant, in a tire shop, or possibly in trucking or light manufacturing. They may live even farther out in the Chicago suburbs or back in some of the city’s more fashionable neighborhoods. The Chicago area may not even be home anymore; they could just as likely live in Florida.

Source: Jack Delano, 1942. Library of Congress.

Despite these economic changes, Delano’s photographs express a timeless sense of vulnerable, yet resilient humanity. We can almost imagine these guys transported to the early 21st century coming into a Northlake pizzeria wearing polos or t-shirts after a day at a local auto dealership or maybe an office in the Loop.

Source: Jack Delano, 1942. Library of Congress.

In the first decades of the Proviso Yards, though, far fewer people commuted from the not yet heavily-populated area to downtown Chicago. Instead, many workers commuted to the yard, located in relative countryside, from Chicago and other parts of the region. Eventually, some would choose to build a life nearby, filling the surrounding emptiness with streets and homes.

Source: Jack Delano, 1943. Library of Congress.

By the early 1940s, Melrose Park and Maywood were home to a number of industries, though very few aside from the Indiana Harbor Belt Railroad were located along or near North Avenue. This focused economic development (stores, taverns, and other services) farther south along other corridors. (Diamond Jubilee of Melrose Park, a book published in 1940 by that city’s chamber of commerce, available online from the Melrose Park Library, provides an illuminating window onto this period of local history.) But with construction of the massive Buick defense plant on North Avenue in Melrose Park, this section of Proviso Township, as well as the adjacent Leyden Township, changed dramatically. The plant, in which aircraft engines were produced, became a landmark industry in the area and helped spur population growth in Melrose Park and in surrounding areas, including the unincorporated area’s just to the west.

The defense plant viewed from near North Avenue in Melrose Park. Source: Buick City.

We passed the building, still standing today, as we rolled through Melrose Park.

Source: Chicago Tribune, January 25, 1941.

Completed just in time for America’s entry into World War II in late 1941, the factory spurred economic and population growth west of Chicago.

Source: Daily Herald, December 12, 1941.

Photographer Ann Rosener captured these images workers producing aircraft engines for the war effort in 1942 for the United States Office of War Information.

Source: Ann Rosener, 1942. Library of Congress.

Thousands of workers from different backgrounds and numerous parts of the Chicago came to work at the plant. While African Americans are visible in the pictures, their presence at the Buick plant was a relatively recent occurrence. According to historian Andrew Edmund Kersten, author of Race, Jobs, and the War: The FEPC in the Midwest, 1941-46, despite a labor shortage and pressure coming from the Chicago Urban League, General Motors, parent company of Buick, had resisted attempts to integrate the facility. In January 1942, no African Americans were included among the 2,300 company workers. A month later, the rolls had doubled to 4,600, but only 52 were African American. Even when the company ranks swelled in July of that year, African Americans only comprised 350, or 4.37% of the plant’s 8,015 workers. By December of 1943, the plant employed 15,233 total workers, though no figures are available for black workers. Rosener’s captions at times attempt to highlight the plant’s racial disparities while still focusing on the supposed unifying aspects of the war. And as the the number of workers at that plant exploded so did the population of the surrounding communities, including the future community of Northlake.

Yes. Very good. Right about there.

Source: Ann Rosener 1942. Library of Congress.

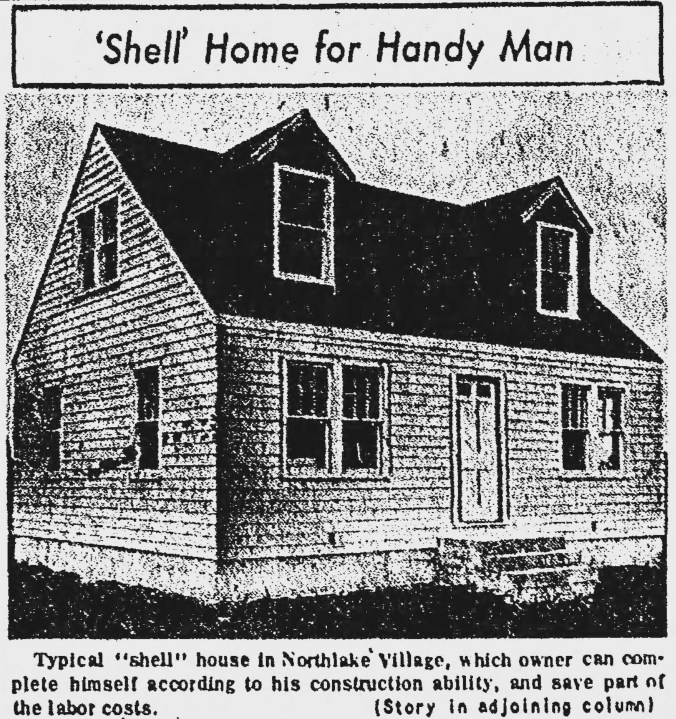

To meet this new demand, developers began advertising and building “semi-finished” or “shell” houses surrounding the plant. Many blue-collar plant workers purchased the homes and improved them with their own labor.

Source: Chicago Tribune, October 3, 1948.

Northlake thus grew up as a working-class industrial suburb, a reputation it held for decades, as a 1991 Chicago Tribune profile entitled “If You Carry a Lunch Bucket, You’ll Feel at Home Here” suggested, almost sentimentally. Homes marketed and built there by the Midland Development and Improvement Company there were charming, but purposefully bare bones. New owners “. . .had to paint the exterior and install partitions, plumbing, heating and electrical fixtures.” Municipal utilities were minimal or virtually non-existent. There were no paved roads or curbs, as this scene from Westward Ho Drive, just about a block north of North Avenue, in 1947.

Source: Edgar Gamboa Navar, Northlake, via Northlake City Hall.

The company turned what the houses lacked into positives, suggesting that “For the man who wants to install his own heating plant, the house is built without a furnace.” Midland, as reported in the Tribune, had other shell options, as well. “Midland eliminates decorating in case the man would like to do his own. A plumber–professional or amateur–may decide he’d like to install his own bathroom. That house will be decorated, have a furnace, but no bathroom fixtures.” (Chicago Tribune, October 3, 1948) Years later in 2014, Mayor Jeff Sherwin reflected on the city’s early development history and stated that “Northlake was built backwards.”

Still, development in the late 1940s was rapid, and it did not go unnoticed by public officials. In 1949, the older and more-established Melrose Park, incorporated since 1882, attempted to annex the growing community in 1949, but residents who had purchased the area’s modest homes, perhaps recognizing the rapidness with which the suburb was growing, resisted the attempt. Northlake incorporated that same year. No longer just a farming community, Northlake was by 1950 a small suburb of 4,361 people. Just three years later, the population reached approximately 9,000 residents.

Now comprised of substantial freight lines and a rapidly growing workforce that increasingly lived in the area, Northlake and the West Suburbs became an industrial powerhouse in the postwar era. International Harvester purchased the Melrose Park defense plant to produce tractor and diesel engines, ensuring that jobs would remain as the area’s population continued to grow. During the Korean War, the factory once again switched to defense production, rolling army personnel carriers off the line. Workers were in great demand, and labor unions became an increasingly powerful force.

Source: Chicago Tribune, October 1, 1952.

Northlake was still growing, but small town enough for a runaway from the West Side to be noticed.

Even more industry–and people came–following the construction of the tollway later in the decade. Automatic Electric, a company that manufactured telephone-switching equipment, built a massive plant in 1957 on a high-end golf course and club, and became the largest industry in the Northlake area. In his book, Northlake, Edgar Gamoa Navar notes that the plant employed over 11,000 people, while Marilyn Elizabeth Perry notes in the Encyclopedia of Chicago, employed around 14,000 at its peak in the early 1970s. Large manufacturing firms such as Rauland, a division of Zenith radio and television, and Alberto-Culver, also located in nearby Melrose Park after the war, This strong base of jobs and suburbanization of the Chicago region helped the population of Northlake swell to 12,318 in 1960, reaching its peak numbers in 1970, with 14,191 residents.

Through it all, work continued at the Proviso Yards.

Chicago & North Western offered good blue-collar railroad jobs veterans returning from Vietnam, and Zenith was a source of many technical manufacturing jobs.

Though some had time to. . .whittle. We kid, of course. Mr. Kohout no doubt spent many hard days and nights working up to the foreman position.

Pizza showed up in great numbers sometime after the war, too, we’re just not sure when. If one did not get a job at the railyards or one of the big companies or wanted to make some extra cash (and was lucky enough to own a car). At this point, most delivery jobs were still in the city, such as this one for Millie’s at 5359 W. Madison in the South Austin neighborhood, as the ’60s progressed, more and more “pizza man” jobs were available in the West Suburbs.

In the following decades, Northlake’s population dipped and rose slightly as industries either came, went, or evolved. Some industries left the area, such as Zenith did in the late ’80s. Other industries evolved into smaller operations such as logistics. The space long-occupied by International Harvester was taken over by Navistar, though truck-producing jobs there were phased out and the plant converted into a technical and testing center after our trip in 2017. Zenith closed its Melrose Park tube factory in 1998, costing 2,000 workers their jobs.

Source: Suburban Trib – November 19, 1982.

Unlike places like Southeast Chicago, where the steel industry’s collapse upended the local economy and a tightly-ingrained way of life, the relative diversification of industry–and the fact that large companies like Alberto-Culver and Jewel retained their nearby facilities–helped Northlake and the West Suburbs avoid widespread dereliction. Today, Northlake is home to approximately 12,300 residents, while the populations of the surrounding communities, despite some slight dips in the last decade or so, have remained similarly stable.

Northlake in fact happens to be the home of a Chicago business institution, Empire Today. Founded by Seymour Cohen as a plastic cover business in 1959, Empire is now a carpet and flooring company with a nationwide reach. One likely wouldn’t guess by looking at the company’s homebase– a non-descript one-story building partially flanked by parked tractor trailers in the western section of Northlake right by the Tri-State Tollway, just steps from the old Zenith facility–that they were looking at the home of one the most recognized businesses in Chicagoland and maybe the country.

Source: Chicago Tribune, June 1, 1971.

Cohen’s Empire–which already possessed a name poised for market dominance–managed to transcend any mundane status as just another local carpet company by investing clever and near-constant advertising. Beginning in 1973, Empire debuted a character that would have a ubiquitous presence on local television for the next four-plus decades, the Empire Man, played by Lynn Hauldren. The 51-year-old Hauldren created the character after several years of independently producing work for a few larger, more well-known firms in the broadcast advertising industry. According to Hauldren himself, several actors auditioned to play the Empire Man before Cohen asked him to take over the role. (Chicago Tribune, December 1, 1997)

Hauldren’s calm, plainspoken demeanor was an instant–and long-lasting–hit with customers. While many local advertisers used a loud, aggressive approach to drum up business, the working-class Empire Man instead talked to customers like a friendly, trustworthy uncle or neighbor.

The approach was a massive success, and considering the context of the time, it makes sense. The country was in the throes of the Watergate scandal, and President Richard Nixon’s increasingly-apparent duplicity shook the faith many had in the country’s strongest institutions. American manufacturing and the labor unions that supplied it with workers started to feel the effects of deindustrialization, globalization, and political change, a moment detailed by historian Jefferson Cowie in his incisive Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class. The common workingman, one could argue, became a source of nostalgia, particularly in the decades that followed the Empire Man’s debut as more and more American factories moved or closed for good. Still, Chicago was much more a blue-collar town in the 1970s than it is today, and upward mobility for the working class was still viewed as attainable. Even with the continued decline of blue-collar jobs, the American Dream ideal persisted, at least anecdotally, even in the way the public viewed the Empire Man character. For instance, in a 1997 profile in the Chicago Tribune, Hauldren stated that was constantly stopped on the street by many people assumed he at least worked as a carpet installer and some even thought he owned the company. With fairness and hard, honest work, the Dream suggests, one too could even their own small business.

Hmm. . .that tune is getting stuck in our heads.

For decades, Hauldren was near-omnipresent in the carpet company’s advertising. Occasionally some other friendly Empire folks would show up, though.

No doubt some of these guys started their morning with doughnuts and baked goods from the old Burny Brothers Bakery at 300 W. North Avenue, around the corner from the Empire facility.

Burny Bros. used to supply dozens of company-owned retail stores in the Chicago area.

Whereas Roeser’s single location endeavored to serve a dense urban neighborhood, Burny’s worked on a much larger scale. The company’s new 145,000 square foot facility, built in 1960, reflected the industrial scale of Northlake businesses, as well as broader mid-twentieth century trends of mass production and consumption.

Source: Chicago Tribune, December 7, 1959.

Despite the fact that Burny tried make their stores seem like a local bake shop–in a 1973 commercial, “It is like finding a neighborhood bakery your favorite food store,” the company was more subject to market forces than neighborhood economic stability. Entenmann’s purchased the company and facility in 1979 and closed in 2004, while the rarely-changed Roeser’s continues to serve Humboldt Park on North Avenue to the this very day. Still, doughnuts or no doughnuts, no matter who showed up to install your flooring. . .

The company made it completely clear that every employee was struck from the Empire Man’s mold.

A point they stressed for decades.

The commercials were even subject of a Son of Svengoolie send-up. How Chicago is that?

“You know the number, right?”

Years later, the bit was acknowledged by the company with the help of Rich Koz.

“Umpire carpets?”

In addition to Hauldren’s sensible approach, Empire invested in giveaway gimmicks such as Michael Jordan-endorsed Wilson basketballs, no doubt a hit in the 1990s during the team’s six championship dynasty. Hmm. . .did Bulls announcer and Northlake native Tom Dore broker this deal between the two Chicago institutions? Or did this deal help him get his job?

Bissell shampooers were the most commonly advertised giveaway, appearing in numerous commercials.

Cohen fully believed in Hauldren’s selling power. And he had proof, too. Cohen was quoted in 1997 saying that the commercials were so successful that “We went through 10,000 Bissell rug shampooers like that, and I think we’ve given out between 90,000 and 100,000 Chicago Bulls basketballs.” A former competitor in the carpet business stated that “If they don’t pay Lynn $300,000 a year, it’s not enough. Because Lynn Hauldren made Empire Carpets. Without Lynn they don’t do those numbers.”

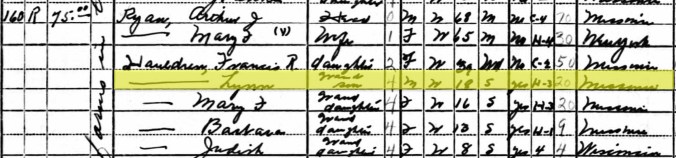

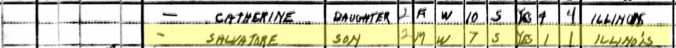

Born in 1922, Hauldren spent his early life in St. Louis. Listed here in the 1940 census is an 18-year-old Hauldren living with his grandparents, mother (a department store salesperson), and siblings in a $75-a-month apartment at 4939 West Pine Boulevard, in the city’s Central West End.

The building, now demolished, was located about right where this parking lot is today.

After serving in the Army during World War II, and Lynn and his wife moved in Wilmette, and later in Evanston.

Source: St. Louis Star-Times, November 19, 1943.

Despite these apparent North Shore white-collar connections, the character Hauldren created managed to encapsulate the hardworking, rooted dependability of folks from more blue-collar places in the region such as Northlake. As then-40-year resident Bob Staerkel stated in 1991, “What brought me here [to Northlake]? We came out and we were looking for a place we could afford. We considered moving as the income grew, but the family said no. The schools are nice, so we decided to stay. It’s not Lake Forest, but as I say, what are you looking for in life? We’re looking for a comfortable place to put on our hat and coat, and this is it.” As another resident, 66-year-old Frank Novak, who owned an aluminum siding business, said the area’s original stock of cheap, unfinished homes allowed for new residents to save money as they made repairs themselves. “We were all together looking for a better life.” Hauldren’s success in advertising likely helped him fit comfortably in the more well-to-do North Shore suburbs. On the other hand perhaps his Midwestern working-class experience of living in with six other people in a cramped apartment at the tail end of the Depression also influenced his worldview in a way that informed the believability of the Empire Man character.

Again, he may have been shrewd at marketing, but his wholesomeness was clearly not just an act: Hauldren also performed in a barbershop quartet called Chordiac Arrest.

Very few Chicagoans can claim to have never heard the Empire’s famous jingle. According to owner Seymour Cohen, Hauldren was the one who came up with the extremely catchy “588-2300, Empire!” tune, which was first launched in 1977. Chicago in many ways was a jingle capital. Writers like Dick Marx (writer of the famous Doublemint jingle for Chicago-based Wrigley chewing gum company, and father of 1980s music star Richard Marx), Dick Reynolds,(whose Com/Track jingle publishing house, founded with William Young was an advertising force), and Dick Boyell (check out his sought after 1960 album for Allied Van Lines, Music to Move Families By) were extremely successful at using clever music to sell products, soundtrack local newscasts, and support sports teams. (Can we include one-time Chicago resident Dick Noel, at least the jingle performing category?) Hauldren built on this local tradition and created advertising gold.

Empire’s jingle was perfect: simple, catchy, and unforgettable. Originally performed by the Fabulous 40s, Hauldren’s vocal group at the time, the jingle is now so famous that it has warranted historical analysis.

Among transcriptions of works by Igor Stravinsky and Steve Reich, YouTube user mead1955, suggests the jingle is a musically rich work of art that stands with some of the greatest.

A lot of hard work appears to have gone into the listening and transcription process: mead1955 apparently viewed over 100 Empire commercials! Wow, that short-lived version from 2003 was strange.

In the early 2010s, Empire Today acquired another local flooring company. . .and another famous jingle. We have no idea how many times Luna Carpet’s “773-202. . .(beep, beep, boop, boop) Luna! (ding)” was sung–and riffed upon–around our household. (Luna in the 1990s and early 2000s also aired commercials with a very different Spanish language jingle in Chicago.) Galaxie, a home remodeling company with another catchy jingle, later became part of the Empire family, as well. Somebody in that company loves jingles. (Perhaps the Frederic Roofing jingle from Hauldren’s St. Louis birthplace is the next acquisition. But if you’re buying jingles and you want to diversify the portfolio, Maull’s, billed as America’s oldest barbecue sauce, is for sale. While there’s an outside chance Hauldren may have been vaguely aware of both companies, we cannot confirm it. We’re not sure when the Frederic jingle first aired, and the Maull’s jingle did not debut until 1974, just after the Empire one. It’s fun to consider the possibility of some sort of connection, though.)

A private investment firm purchased Empire in the late 1990 and took the brand nationwide. Despite its success, by 2016 Empire Today went up for sale and was later purchased by a large private equity firm. Hauldren, an icon of Chicago advertising, passed away in 2011. Through all of these changes Empire, the famous jingle and even the Empire Man live on.

But weren’t in the market for carpet; we were renters after all. Pizza, though, we could do that. Traveling west on North Avenue, we were essentially on the main street of Northlake. There’s no typical downtown as one might expect and there’s a general sense of placelessness, with notable landmarks that tip off the brain to specific location. Northlake, after all, developed in the 1940s and ’50s, too late for a dense main street with two- and three-story commercial buildings. This was the land of the automobile. Thus, North Avenue reflects, boasting six lanes for vehicular traffic. Surrounding homes in the community, reflective of their “semi-finished” status when they were originally built and purchased, were still on the modest side–single family Cape Cods and small ranches, but typical of the era, the yards are larger than the ones found throughout the city of Chicago, with spacious front and back lawns. Many commercial structures–most located along North Avenue–are modest, as well, and they generally reflect the automobile culture of the 1950s and 1960s during which Northlake truly grew up. For instance, a drive-in called Quick-Chek was once located at 322 E. North Avenue. A strip mall currently occupies the site. (There was also a place called the Friendly Pup somewhere in Northlake, too. Where? Sounds like something Ernie would like.)

Source: Chicago Tribune, June 19, 1960.

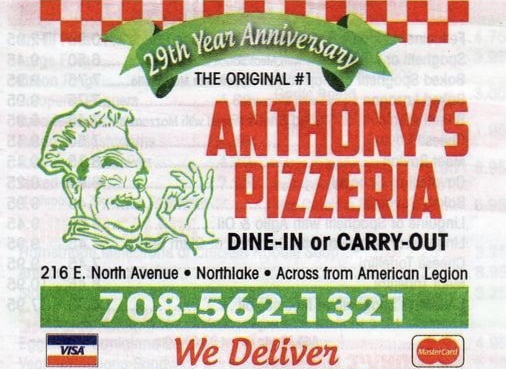

In one of these one-story structures–an early strip mall–just about a mile west of the old defense plant, we noticed a small business with a few parking spaces called Anthony’s Pizzeria. A small (by today’s standards) sign announced carry out and delivery, and the building was embellished with red and white awning–itself emblazoned with large block letters. Both the sign and the awning listed a seven digit phone number (and no 312, 773, or 708 area code) which suggested the business had been around for at least a couple of decades, though not as old as the old West Side places that used the two-letter prefix followed by four digits.

According to a menu available online, Anthony’s, located at 216 East North Avenue “Across from the American Legion,” has indeed been around for three decades, extending back closer to some of Northlake’s most well-known pizzerias. (There is also an Anthony B’s Pizza on Broadway in Melrose Park which opened in 1991. Are the two pizzerias related? Did this lead the menu proclamation for the Northlake restaurant as “The Orignial #1”?)

Source: Yelp.

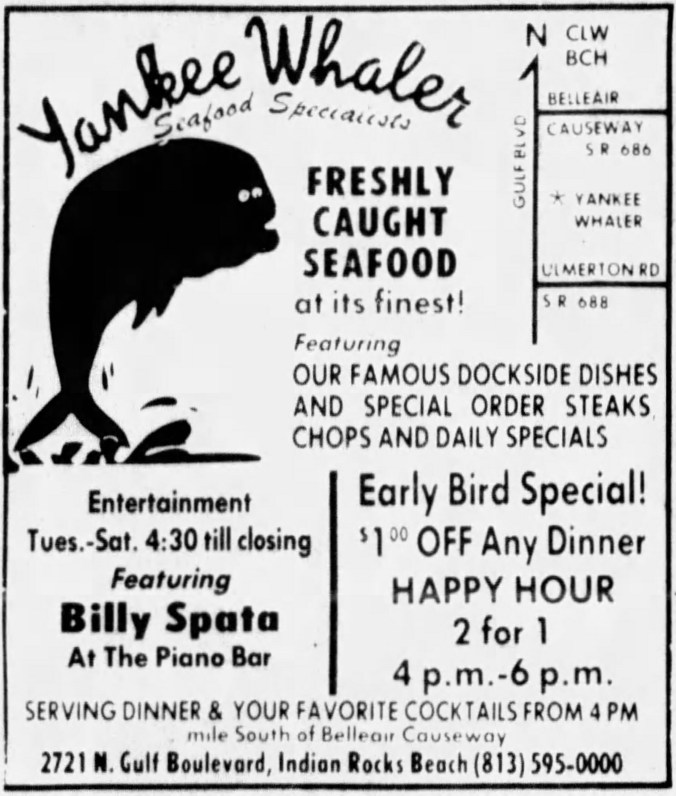

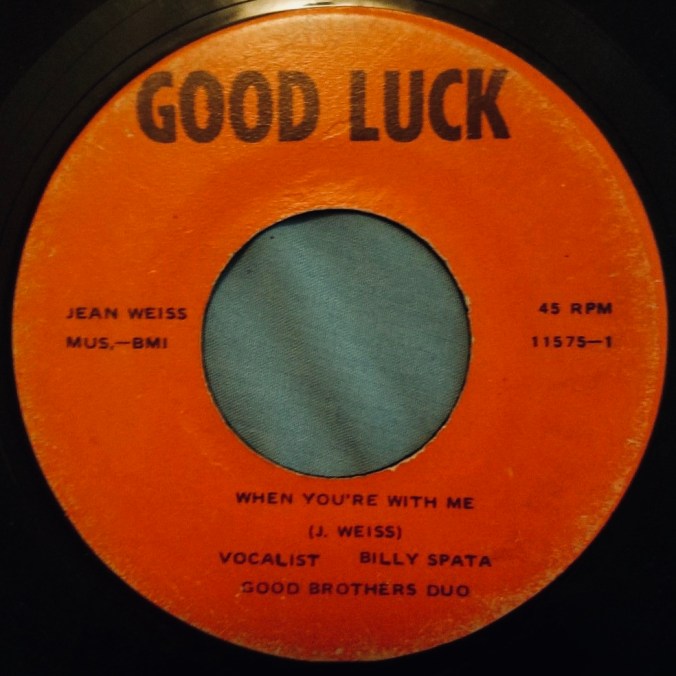

Meet Jim Spata: Northlake pizza pioneer. A native of Rochester, New York, and early Northlake resident, the Italian American Spata worked for the Chicago & Northwestern Railroad, likely at the Proviso Yards. He was listed in 1936 in company records as an “office boy” and later as a clerk in the 1940 census. His son Paul was listed as a “locomotive fireman” for the company in the mid 1950s and was still on the company rolls in the mid ’60s.

Source: Edgar Gamboa Navar, Northlake via Northlake City Hall.

While working for teh Chicago and North Western Railroad, likely at the Proviso Yards, as a “messenger boy” (company records three years later in 1936 call him an “office boy”), the nineteen-year-old James Spata spent his free time as a competitive lightweight boxer.

Source: Chicago Tribune, February 11, 1933.

He then operated a shoe store and barber shop at 149 East North Avenue in Northlake. Later, he opened Spata’s Pizza across North Avenue from this building with his son, James Jr., who was a few years younger than Paul and also worked, as a clerk, for the Chicago & North Western Railroad in the mid 1950s. We’re not sure if Paul and his mother, Grace, were involved in the pizza venture.

Source: Edgar Gamboa Navar, Northlake via Northlake City Hall.

Spata’s Pizza is well-remembered by Northlake residents of the era. It appears the carryout and delivery business opened around 1962 and was apparently for sale in 1968. Whether Spata’s Pizza closed or not–or was even sold to a new buyer–we can’t say for sure.

Source: Chicago Tribune, May 2, 1968.

In 1973, Jim Jr. and his wife opened Valeo’s Pizza in Kenosha, Wisconsin, a business they operated for the next 40 years in a mid-century building that looked like it could be on North Avenue, surrounded by modest homes and even some open fields, in Northlake. In the early 2010s, they sold the business to their son, Eric, and his wife, Christal. The new owners opened a second location soon after, and Christal was named a finalist as young entrepreneur of the year in 2018. The team is very active in keeping the Spata pizza tradition alive. It’s interesting to learn that a Kenosha pizza tradition has its roots in one born in Northlake.

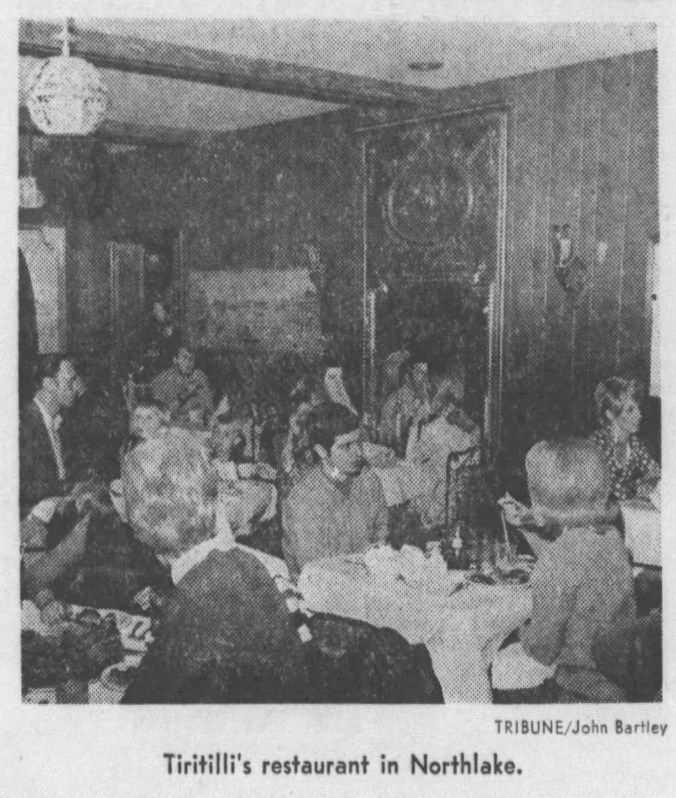

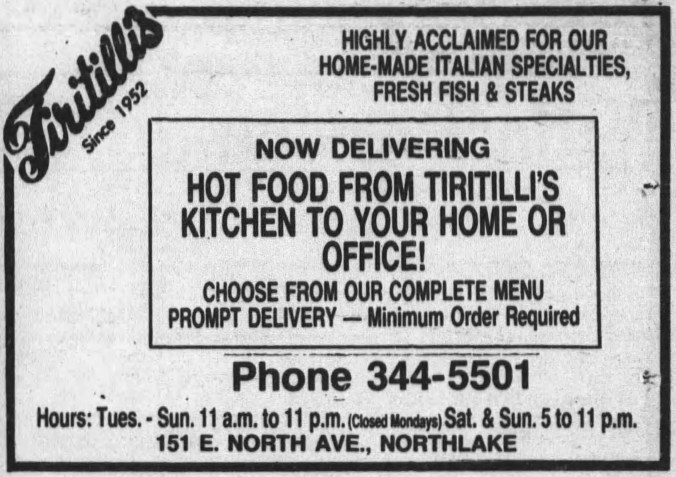

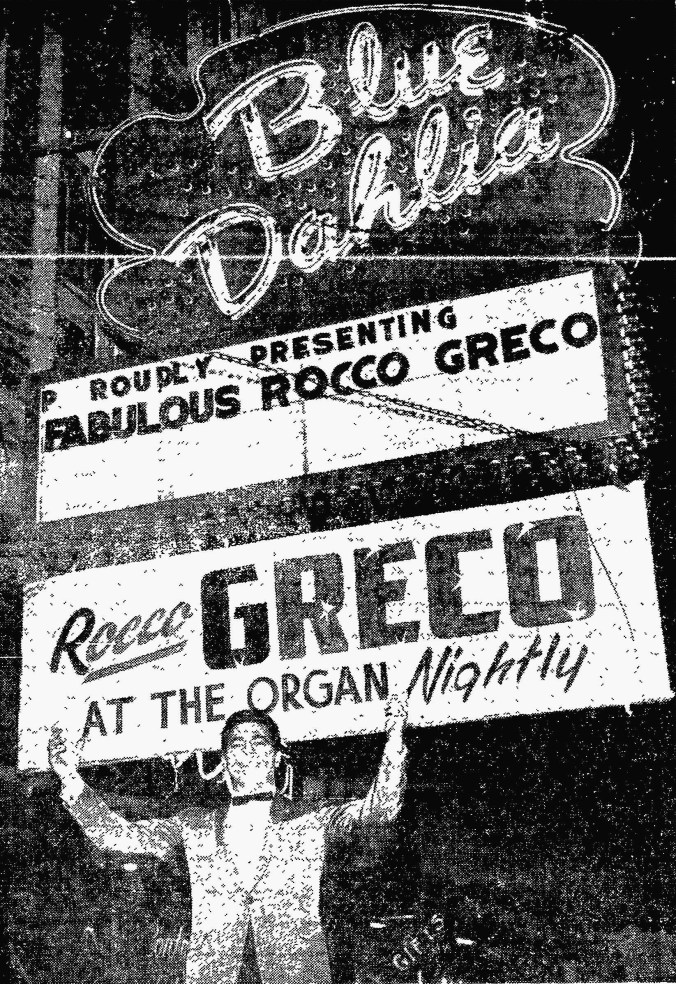

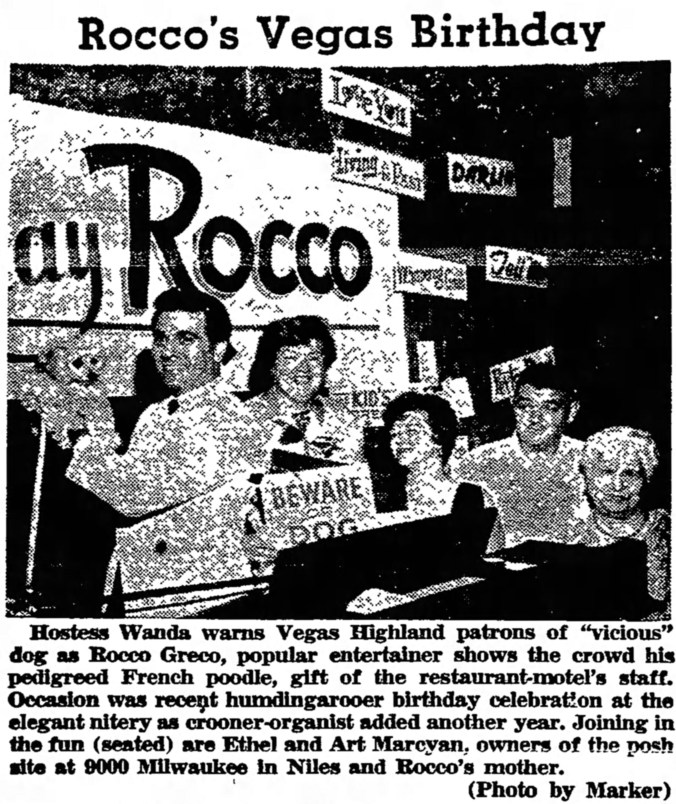

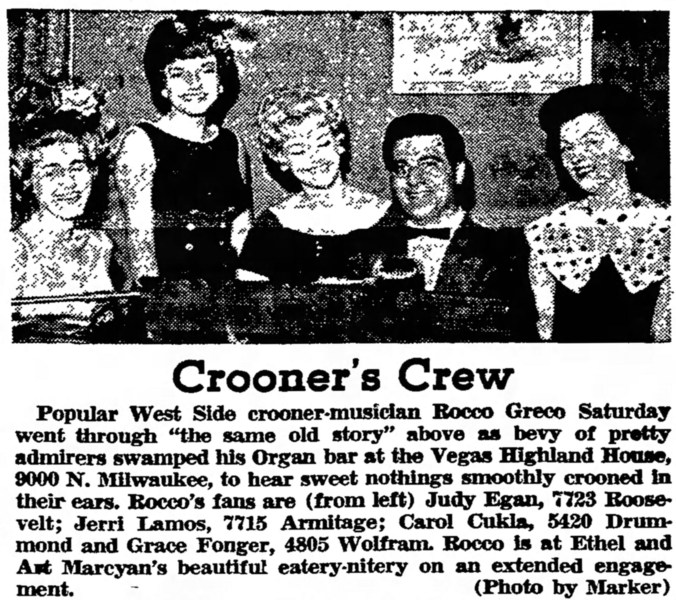

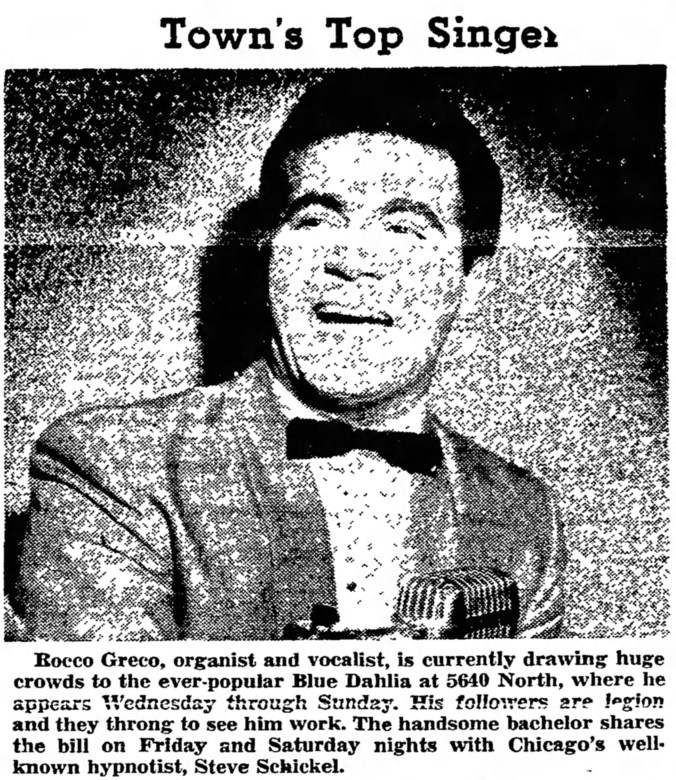

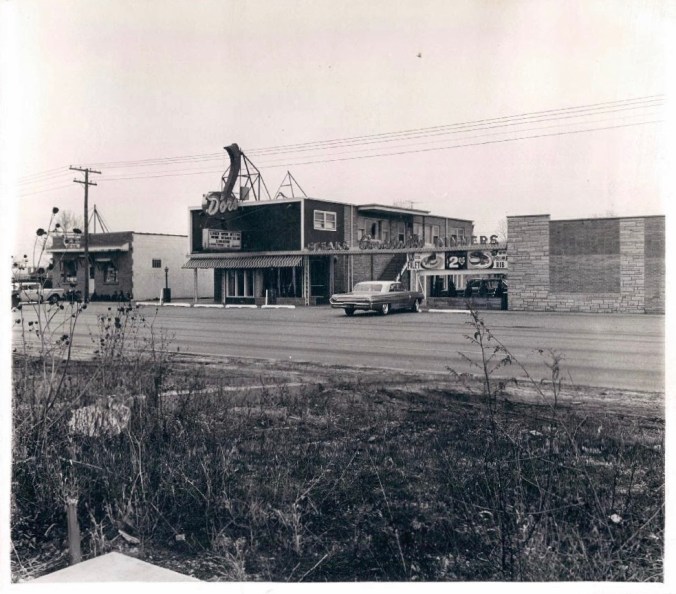

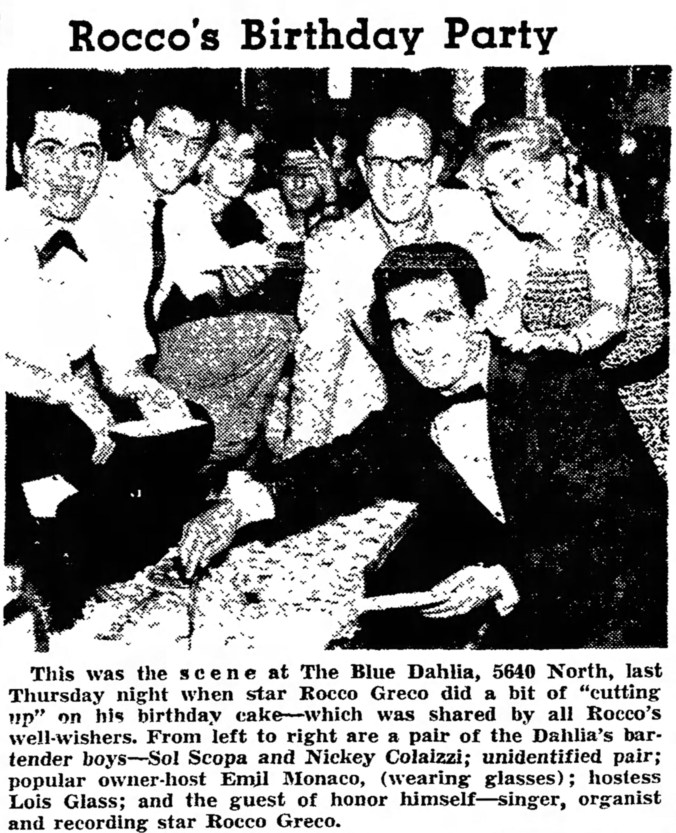

Next door the old Spata’s shoe store and barber shop–and across North Avenue from Spata’s Pizza–the revered Tiritilli’s Restaurant stood just about a block or so west of Anthony’s at 151 E. North Avenue. I think I see a jukebox! “Shrimp Boats?” Perhaps “Getting to Know You?” Ever heard of a guy named Roc-co Gre-co?

Source: Craig’s Lost Chicago.

Natives of the bungalow-lined streets of Maywood, brothers Bernard and Joel Tiritilli first opened a pizzeria in 1952, right around the time they graduated from Proviso Township High School, later known as Proviso East. Bernard was a member of the Class of ’52.

As a member of the Class of ’54, Joseph, or Joel, must have joined on later. Their parents Margaret and Anthony, a salesman for Peoples Gas, also had an interest in the business until Anthony’s death in 1958 at the age of 49.

Perhaps Bernard and Joel enjoyed eating at Boezio’s so much that they wanted to give the pizza a try for themselves.

Source: Forest Park Review, June 13, 1957.

Tiritilli’s was a family-run place.

Source: Chicago Tribune, January 4, 1976.

“The Tiritilli boys, Bernie and Joel” got a lot of help from the rest of the family.

Source: Chicago Tribune, May 17, 1975.

All for local Northlake and West Surbanan diners to enjoy with their own families and good friends.

Source: The Roselle Register, August 30, 1968.

While Spata’s focused on carryout and delivery, Tiritilli’s was more of a dine-in operation with artwork-adorned wood-paneling, tablecloths, and candles.

Source: Chicago Tribune, April 19, 1970.

But they delivered, too.

Source: Chicago Tribune, February 20, 1985.

Working at the restaurant could be a good job.

Source: Chicago Tribune, March 24, 1971.

Pizza was a specialty at Tiritilli’s, but a number of Italian entrees were very popular, as well, including many pasta dishes.

Source: Need date

Bernard’s wife, Barbara, wrote a cookbook containing recipes for the restaurant’s popular dishes called Garlic By Candlelight. Are there any copies out there?

Source: Los Angeles Times, September 17, 1970.

But again, feeding families was a main focus of Tiritilli’s.

As well as the hardworking folks of Northlake.

Source: Chicago Tribune, November 4, 1983.

Bernard and Joel ran the Tiritilli’s Restaurant until Bernard tragically lost his life in a car accident in 1986. Joel Tiritilli sold his interest in the business in the late 80s, though we’re not sure if that was end of the famous restaurant. Joel and his wife, Rita, however then opened a new cafe in Willowbrook, affectionately named Bernard’s in honor his late brother, and it too was a family affair. Joel and Rita’s nephew, Jeff Mauro, currently hosts Sandwich King on the Food Network and even visited Bernard’s to film an episode.

While the original Tiritilli’s is now the site of yet another AutoZone, Bernard’s in Willowbrook is still in business today.

Source: Bernard’s Cafe & Deli.

While the suburbs remain heavily-populated economic engines of Chicagoland and most cities across the country (and continue to grow), in years many younger generations of have returned to the central cities attracted by culture, diversity, and opportunity. This is certainly true in the Chicago region where many neighborhoods draw twenty- and thirty-somethings often looking for life different than the suburban one’s of their youth. Accordingly, Susan and Kristin Tiritilli, daughters of Bernard and Barbara, operated the popular Tilli’s not in Northlake, Melrose Park, or anywhere else out west, but instead in North Side of Chicago neighborhood of Lincoln Park beginning around 1996. The restaurant was a success and considered a neighborhood staple. The Tiritillis and the restaurants regulars were met with shock when the owners experienced a brief loss of its lease in 2009. Tilli’s hung on for a couple of more years, though, until officially closing in October 2011. The tide of gentrification is rapid in Chicago, and Tilli’s run was a good one considering many new businesses come and go within just a couple of years.

Signage remained on the vacant storefront on Halsted at Armitage for almost a year until the building was demolished in 2012 and replaced about a year later with a business that could afford the area’s ever-increasing rent. Since then the Tiritillis continue to cook, keeping family tradition alive.

Both Spata’s and Tiritilli’s are remembered very fondly current and former Northlake residents, with common discussions regarding both places on Facebook. Some other former pizza options in Northlake and the surrounding area included Johnny’s Pizzeria was located on Wolf Road at Doyle Drive across from St. John Vianney High School, Pete’s Pizzeria on Grand in Franklin Park (now the site of Gianna’s), Tony’s in Stone Park, and Armando’s on Mannheim Road. What are these places?

Here’s a place on Mannheim Road for sale in 1956, though we can’t figure what town it was located.

Source: Chicago Tribune, August 19, 1956.

This tavern and pizzeria was for sale in 1977.

Source: Chicago Tribune, September 29, 1977.

The ’80s particularly had a noticeable number of pizza ventures. These two places were for sale in 1980 and 1981, respectively.

This ad comes from 1985. Newly remodeled and lots of parking. . .is this the future Anthony’s? A menu for Anthony’s online dating probably to before 2018 says that they’ve been around years, but online records suggest the business was started in 1989. So this may be a few years too early to be that establishment. The answer to this likely lies with longtime Northlake residents.

Source: Chicago Tribune, November 21, 1985.

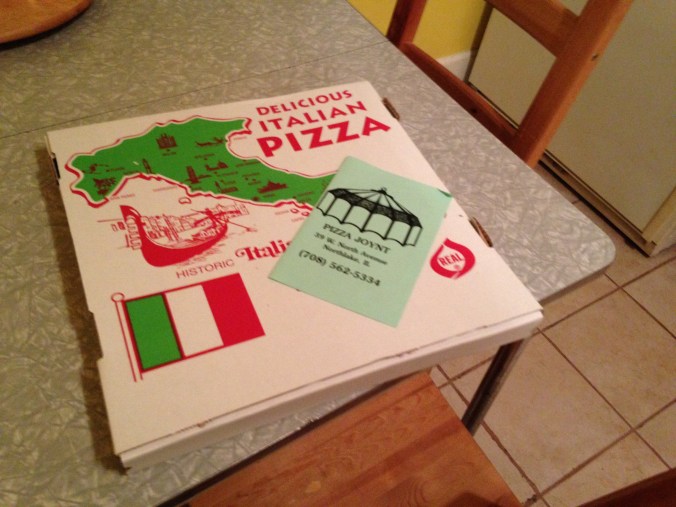

With each of those local pizzerias gone, Anthony’s remains one local establishment to carry on their legacy. We strongly considered stopping at Anthony’s, but made the decision to continue chasing down our current order instead. As we continued west, the commercial landscape became more and more late-century suburban, with a number of chain restaurants and stores with parking lots, such as a large Menard’s (a company with an amazing Empire-worthy jingle). Just past Wolf Road in a one-story story brick building relatively older the much newer Home Depot, Wal-Mart, and Sam’s Club–which comprise the site of the old Northlake Shopping Center–located behind it, we found what we had been looking for all along. After traveling through a world of historical pizza, we arrived at Perry’s Pizza Joynt.

Perry’s parking lot was mostly full. We managed to find a spot, but it appeared that patrons to come here and stay for a bit, not just pick up a pizza and head home, especially on a wintry night like tonight. The sign–with an old-timey font that was popular in the 1970s and early ’80s–indicated to us that we might be in store for a pizza parlor of that era, similar to Barnaby’s, a classic restaurant that once used to many locations in Chicagoland.

Source: Hammond Times, May 21, 1976.

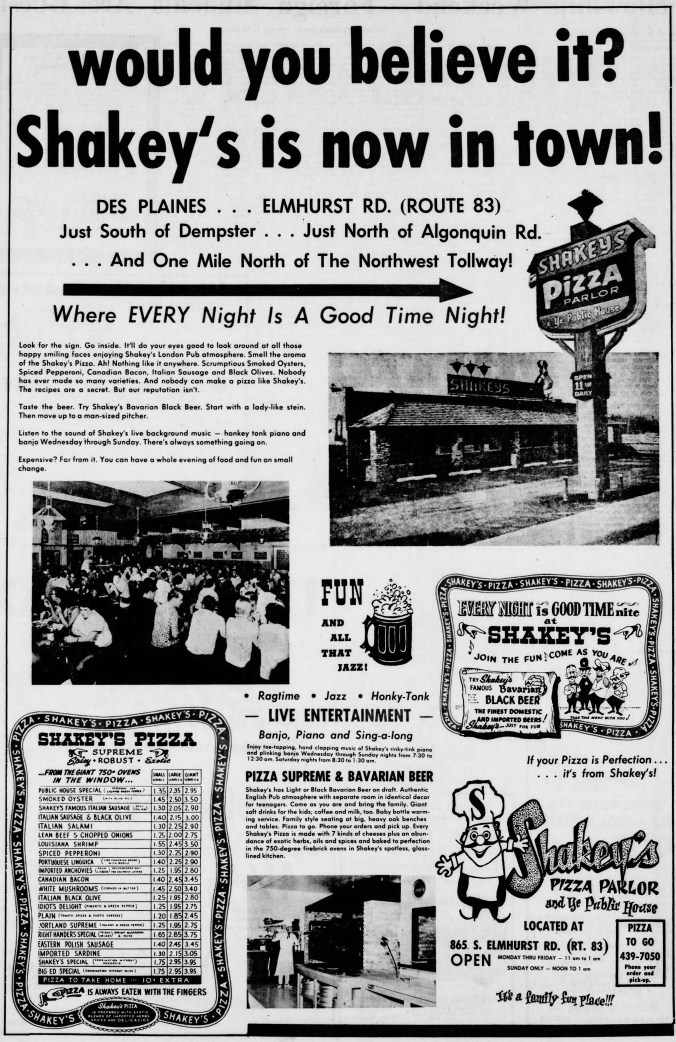

Or possibly the once well-known Shakey’s, which had a nationwide collection of franchise locations.

Source: Arlington Heights Daily Herald, June 30, 1966.

The Northlake Pizza Joynt is not the only the place in Chicagoland that goes–or has gone–by the name of Perry’s, either. There’s the longstanding Perry’s Pizza in Park Ridge (which offers a “Gutbuster” pizza), and there used to be one in the Kane County (and partially still in Cook County) community of East Dundee. As far we know, though, both places are unrelated to the Joynt.

Source: Cardinal Free Press, March 22, 1967.

In the 1950s there was even a Perry’s Restaurant & Lounge in the Harvey, Illinois, right in the Posen/Dixmoor area, not too far from Frank’s Pizza. The business evolved from Perry’s Dinette to Perry’s Restaurant and Cocktail Lounge over the course of the decade.

Reportedly “Ideal for bowling banquets,” it looks like they featured some loungey entertainment, too.

Of course, Perry isn’t an uncommon name. We’re just trying to cover our bases in case there is a connection, though. But as far we know, this pizza joint is singular venture.

Through these doors. . .

We were promised. . .

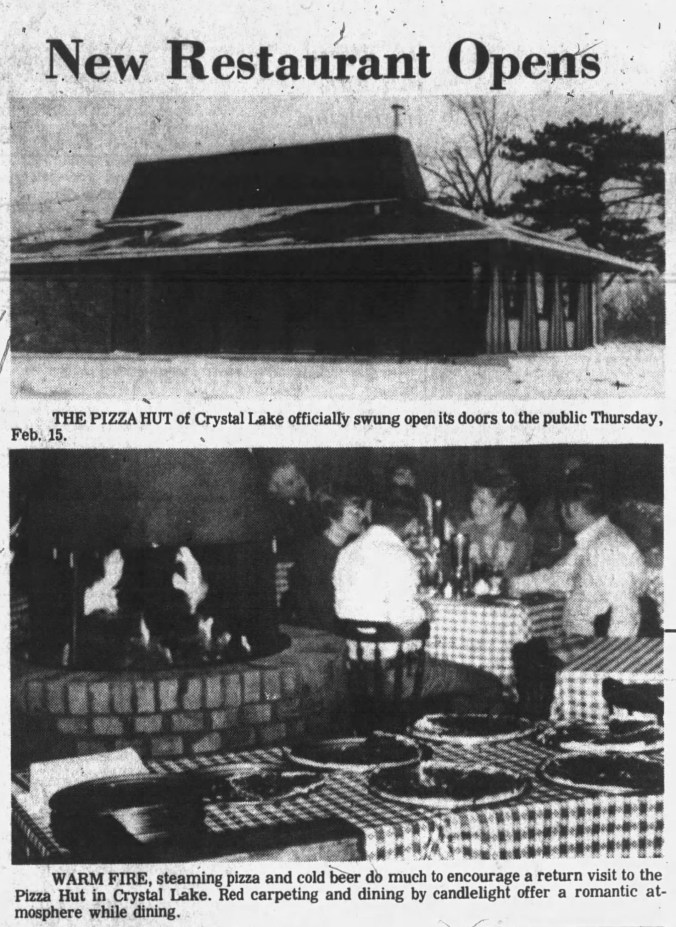

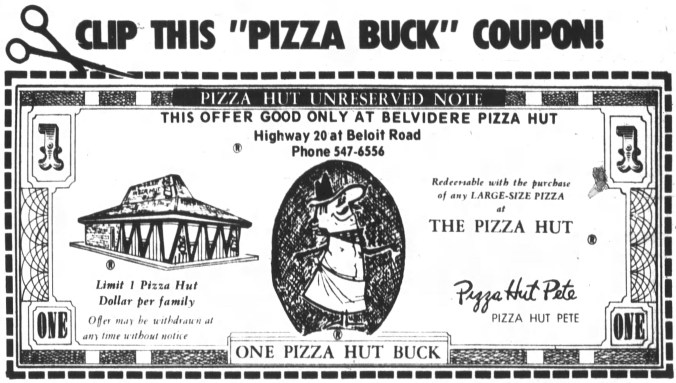

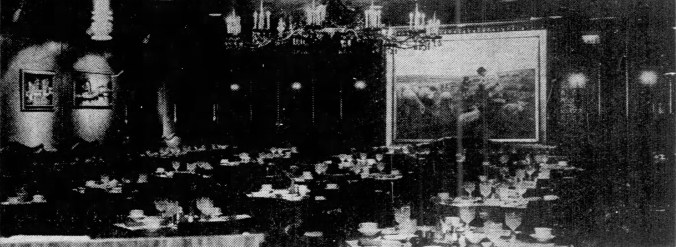

But before we got to the pizza, though, just inside a second set of door’s gave us a choice: a door marked “Restaurant” and another one to the right marked “Lounge.” We chose the restaurant, of course, and what an incredible sight it was. Though I hoped not to show it to the locals dining in, my eyes were wide with wonder at what I was witnessing. Lots of illuminated stained glass, colorful carpet, and dark wood-paneled walls covered with signs and photographs. There were several long tables perfect for large groups or families with kids. This must have been what Pizza Hut was going for in the 1970s and ’80s, though standardized, watered-down version (no judgement here; that’s one place where we learned to love pizza and pizzerias). Why, yes, Pizza Hut’s red carpet and candlelight do make for a romantic dining atmosphere.

Source: The Herald, February 20, 1973.

Despite going for dining elegance on one level, pizza parlors had to appeal to all members of a family. Like Shakey’s, Pizza Hut had a cartoon character, Pizza Hut Pete, to appeal to children.

Source: Belvidere Daily Republican, November 30, 1973.

But we would argue that real, classic family pizza parlors like this are disappearing.

Neon signs and a few TVs, but not too much of the latter to be distracting. Unfortunately there wasn’t an “8-by-“10 glossy nor a theatrical release poster signed by Friday the 13th: A New Beginning and Return of the Living Dead co-star Mark Venturini, the fondly-remembered Northlake native and local West Leyden High School graduate, though we hope there’s one there somewhere.

We also didn’t notice a photo of Northlake’s arguably most successful musical product, Frankie Sullivan.

Born in 1955–the same year Jack’s Shrimp Boat opened for business on the West Side–the Northlake native’s music would be heard around the world, but had humble roots in the West Suburbs of Chicago. Is Frank M. Sullivan, 1961 Northlake mayoral candidate, Frankie Sullivan’s father? His grandfather, perhaps? The full name of Survivor’s Frankie Sullivan is Frank Michael Sullivan III, after all. Note the cameo by our famed James Spata, who then also served as treasurer for the Northlake Chamber of Commerce.

Numerous candidates including Sullivan were looking to unseat Mayor Henry Neri.

Frankie Sullivan attended West Leyden High School several years before Mark Venturini. He even played football and basketball.

After playing local garage bands, he joined Chicago-based 1970s rock band Mariah, who recorded an album for United Artists in 1975, at the age of 19.

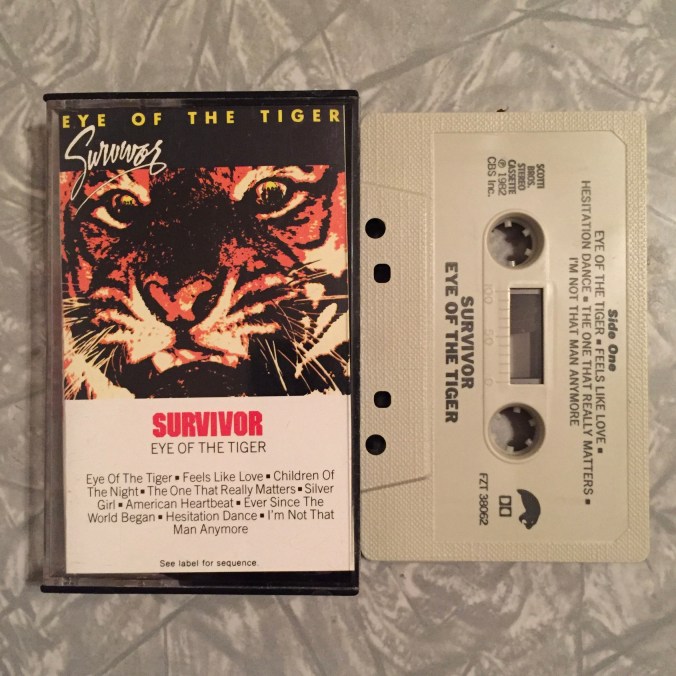

Mariah was short-lived, and it was a few years later that he achieved his greatest fame as founder, writer, and longtime guitarist for AOR rock band Survivor.

Sullivan co-wrote and produced many of the band’s track’s with fellow founder Jim Peterik (below, far left), the Chicago suburbanite previously famous as a member of the Ides of March. Following the breakup of that band, Peterik worked writing commercial jingles (!), including one for basically-only-popular-in-Chicago Old Style beer. According to Peterik, the money he made from writing jingles paid for the original Survivor demos. Unbelievable. Jingles may be the unseen economic engine of Northlake and the West Suburbs.

While not always a favorite of critics–Rolling Stone backhandedly deemed the band “faceless”. . .in the introduction to an interview with Sullivan–we think it’s time for a reevaluation of the band’s work. If not a Lennon and McCartney or a Mick and Keith of the West Suburbs, Sullivan and Peterik were at least a Perry and Schoen (and Rollie and Cain, etc.) of the West Suburbs, writing, producing, and performing a number of wonderfully rocking–and often overlooked–tracks. The band’s self-titled debut is pretty typical workmanlike arena rock, that moves on the spectrum from largely unmemorable to fairly solid. Songs like “Can’t Getcha Offa My Mind,” “Freelance,” and even “Somewhere in America,” the local hit, could be easily confused with Foreigner, Kansas, or a less dramatic Journey from the same period. Moodier tracks like “Whatever It Takes,” “Nothing Can Shake Me (From Your Love),” and “Whole Town’s Talkin'” is cut from a similar cloth but contends that the band has a more interesting side.

The follow-up, Premonition, is a noticeable improvement over its predecessor, with the band closer to finding its own voice. “Chevy Nights,” the opener, may draw from the same well as the Ides of March’s “Vehicle” but is tuneful, catchy, and memorable in its own right (With sole songwriting credit going to Peterik–and the brand mention–one wonders if this song about nights in a Chevrolet actually grew out of a jingle to sell Chevys). “Summer Nights” and especially “Heart’s a Lonely Hunter” hint at–though stop short of–the band’s future bread and butter, the power ballad. Standouts include “Poor Man’s Son,” a tale of love across class lines (after growing up working-class Northlake? Or perhaps Peterik’s native Berwyn?), and “Runway Lights,” a track highlighting ever-growing distance between one’s dreams and home, between change and stasis, between a new life and the loved ones left behind. Still, those great tracks express a few standard ’70s rock cliches about life on the road and on the stage.

Of course, we say “cliche” now, but we suppose if we were a suburban Chicago kids (or hounds) in the ’70s and our mom and dad worked at Automatic Electric or International Harvester (for instance) while we lived in a house that our grandparents had to install everything, then we might have a different–more romantic–perspective about rock ‘n’ roll. No matter how cool local industries tried to make the old hometown sound.

But with Eye of the Tiger, Survivor slicked things up a bit and hit their stride, moving closer to the sound that would define the band. Straddling the world between rock and pop–as was the rule of the day at the time–the band’s 1982 album, their third, was one of their biggest hits.